When we hauled Del Viento in 2011, we did so only to paint the bottom. I also re-greased the Maxprop. We were back in the water in just a few days.

But I noticed that during those few days, the concrete beneath our rudder was wet, all the time. A slow drip from the lower hinge assembly was the source of the water. I did nothing about this and we launched.

The notion that our rudder was filled with water bothered me and nagged at me, for about a month. Then, the discovery of bigger boat problems pushed all thoughts of our water-logged rudder aside.

In 2012 we hauled again, this time for the express purpose of installing transducers for our new instruments, out and back in. But a persistent drip over those 48 hours reminded me that we still had a rudder filled with water.

I Googled about this and read everything from horror stories of rudder failures brought on by water intrusion to platitudes seeking to reassure me that all rudders leak. Accordingly, remedies ranged from rudder replacement to drilling drain holes and epoxying them up before launch. This year I resolved to cut a panel out of the side of our rudder to see what’s what.

Part of what informed my decision was my understanding that rudders are constructed with an internal framework comprised of a vertical post (the part that passes through the hull and which the tiller or wheel rotates) and flat bars welded to it (perpendicular) that transfer the rotational force of the post at the leading edge of the rudder to the rudder’s surface area that extends aft, to the trailing edge. Then this framework is covered in foam that is shaped like an airfoil. Finally, an outer fiberglass skin is applied over the foam layer.

The danger I read about with regard to water intrusion is corrosion. If the water enters the rudder at the difficult-to-seal place where the fiberglass skin meets the rudder post, then it can be assumed that bond is compromised. And if that same water corrodes the welds that attach the flat bars to the post, the rudder can fail such that the post rotates independently of the flat bar, foam, and outer fiberglass skin assembly.

So knowing we’d spend a couple weeks hauled out in a hot, dry place and craving the piece-of-mind I’d gain from seeing what was happening inside, I attached the cutting wheel to my grinder and went to town. Once I’d cut completely through the 3/16”-thick skin, it took only a small bit of prying to pull the cut panel off.

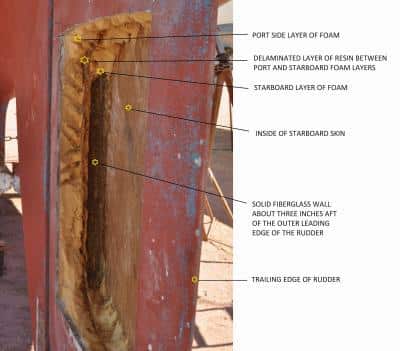

By this time, I’d read everything I could find about rudder construction and repair. There, beneath the panel, was foam like I expected, but not the foam I expected. This was foam from my childhood, that orange-colored 1970s stuff that is not very dense and turns mealy when you rub it between your fingers. I could poke my finger into it and leave a hole. And it was saturated so water squeezed out of it when I did. Only a portion of it was not delaminated from the fiberglass panel I removed.

I grabbed a big piece of it and pulled it out. There, halfway to the other side of the rudder was a thin wall of resin—I’m guessing polyurethane resin. It was cracked all over and brittle like the sugar melted over crème brulee. I suspect it was used to bond the two sides of foam, but there were wide gaps between the two halves.

I dug deeper, until I reached the other side of the rudder. I removed all the foam and resin. That’s all there was, no flat bar or webbing to connect all this to the post.

Where was the post?

I dug forward, removing all the foam I could towards the leading edge. It wasn’t a post I found, but a solid fiberglass wall. The post was seemingly encapsulated in a cavity immediately aft of the leading edge of the rudder and it seemed the skin was a part of this seeming exoskeleton.

I sent pictures to a respected colleague who works for Good Old Boat and Professional Boatbuilder magazines. He hadn’t seen this before, but asked if he could publish a picture I sent him, to solicit reader knowledge. That was good, and I am eager to learn more, but I’m on the hard in the Sonoran desert. It’s over 100 degrees every day, there are biting ants everywhere, and I’m struggling to stay hydrated and finish these projects so we can get back in the water.

So with the knowledge that the rudder was working fine when I opened it up, and with a nod to the Japanese craftsmen who constructed it more than 36 years ago, and with the confidence that I could put it back together at least stronger than it was, I set to work.

First I drilled four drain holes near the base of the rudder and let everything sit in the dry air for two weeks while I attended to other jobs. Then I came back to the rudder and cleaned everything I’d excavated, vacuuming foam bits from the crevices and wiping the surfaces down with acetone. I mixed more than two cups of West System epoxy and poured it slowly into the spaces between the foam halves and the gap between the skin and the lower section of foam. Then I pushed thickened epoxy into the vertical gaps I couldn’t pour into, re-bonding surfaces that appeared to have not been bonded for a long time.

Once everything was cured, I sprayed nearly a full can of dense, closed-cell polyurethane foam into the spaces where it could stick and expand and harden without falling out. Then I epoxy-wetted big areas of the inside surface of the panel I cut out, pushed it into place, and used scrap lumber, rope, and clamps to hold it in place, with pressure.

I’d noted the areas still requiring foam and drilled five holes in the outside of the rudder to spray through, carefully working the straw up as I sprayed, filling every crevice until foam oozed out of the seam and holes. Once dry, I removed the lumber and clamps and used the grinder to expose just over 2.5 inches of raw fiberglass on either side of my cut, a shallow angle that would allow me to make a scarf splice-like fiberglass repair.

I cleaned the entire surface with acetone and then wetted it with epoxy before wetting and applying 5-inch-wide strips of woven glass over the seam. Then I built it up with a 2-inch strip, another 5-inch strip, and then coats of thickened epoxy the next day. Once faired and sanded, the rudder was stronger than when we hauled and all that was left was bottom paint.

I still don’t understand the construction—it may be that there are perpendicular supports attached to the stock down lower, or perhaps this design, as it is, is perfectly robust—but I am confident it is stronger than when we hauled and will probably remain so for the next 36 years. I do look forward to hearing any feedback from the Professional Boatbuilder readership.

We’re back in the water now, underway with a clean bottom, a rudder mystery solved, a transmission not threatening to dump all its fluid, and a mast that will never again interrupt a peaceful night’s slumber. Oh, and even close-up, Del Viento now gleams, looking prettier than ever.

–MR