Lucky enough to have learned to sail when I was a boy knocking around Maine’s Kennebec River in a small wooden centerboard sloop, I harbor a history of mixed feelings about boats. Most of these emotions are positive, even ecstatic. Feeling the wind and exploiting it in a moving boat — there is a profound sense of independence. And yet when I first learned it, this seemed too miraculous. I can recall feeling a premonition that sailing is too glorious to be anything other than temporary, like a lovely Christmas morning under a pretty tree that will be in the trash tomorrow.

Will the day ever come when I will have to give up boats? Until now, the answer has been no. Yet when I have been asking this question recently, six decades after those early joys on the Kennebec, I have a sense that the ground rules are changing.

While we are never too old for holidays, some other things must inevitably be given up. The irony is that the abolition is at my own initiative. This past June, because of something I learned about myself, I decided to cut back on boats, swearing off the type of sailing that I most deeply love, which is going far out to sea. I made this decision last summer in England because I decided that, at age 74, my basic capabilities were gradually failing.

When a very fine yacht club on the Isle of Wight invited me to come over from the States and present a talk on yachting history at its clubhouse, my wife, Leah, quickly organized around that superb event an equally superb shoreside vacation on a theme (English cathedrals and pilgrimage sites) of profound interest to us both.

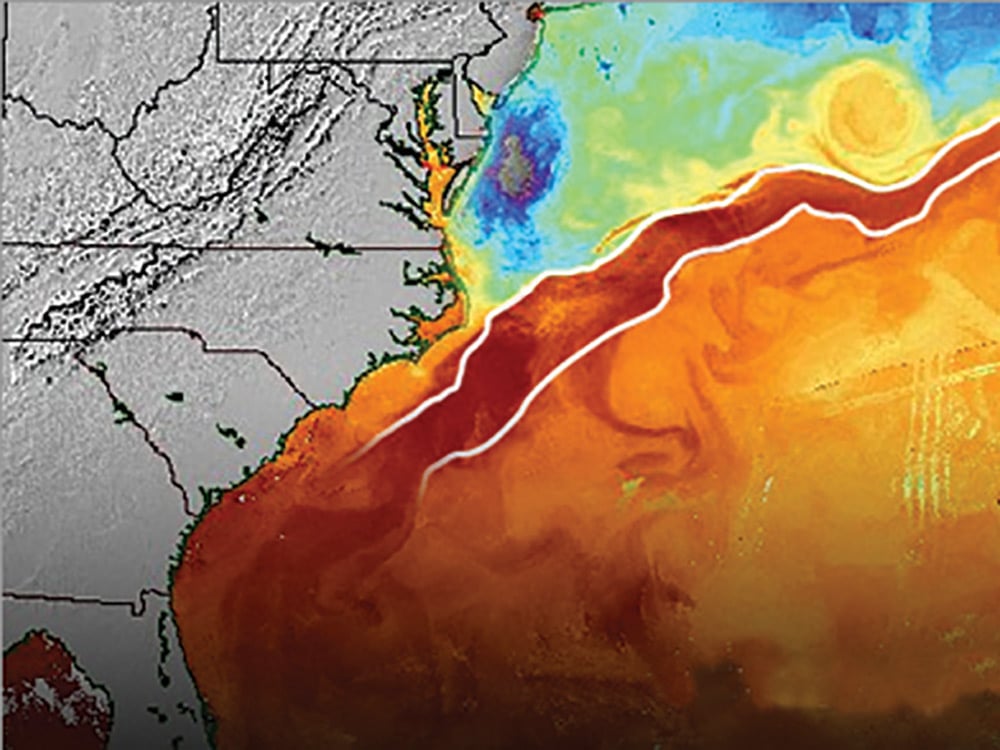

I meanwhile arranged to get in some sailing after we left England by joining the crew of a classic wooden yawl that would sail one of my most favorite challenging routes, 650 miles from Bermuda across the Gulf Stream to the States. Taking both prospects — the tours, and the delivery — seriously, I immediately expanded my fitness regimen, with daily long walks and extensive upper-body exercises.

“One of my most important safety rules of thumb is that any sailor who is physically or mentally ‘off’ in any way that makes him unreliable doesn’t belong in an offshore boat.”

But once we were in England, our ambitious and seemingly sensible plan began to fall apart. We had not considered one important question: Could I do all this? I was eating well and sleeping well, my recent physical examination had been a success, and the jet lag was well behind us. Still, by midafternoon on most days in London or Canterbury or Salisbury, my previously resilient body and brain were scrambled to the point of being distracted, forgetful and (so I was informed) grouchy. After a week of this, Leah tactfully wondered out loud if I really was up to the Bermuda delivery. My immediate response was a defiant husbandly yes. Still, I knew exactly what she was saying. I decided to track myself and make my own decision. By the end of a day of constant self-examination, I realized that though I was generally in good health, I was not at my old state of resilience. I felt more tired, forgetful and distracted than I could recall.

I asked myself one searching question: Would you want to have someone at this stage in your watch in the Gulf Stream?

My answer: Probably not.

With that, I decided to withdraw from the delivery crew. In my reluctant email to the owners, I wrote, “One of my most important safety rules of thumb is that any sailor who is physically or mentally ‘off’ in any way that makes him unreliable doesn’t belong in an offshore boat. … Now three months into my 75th year, I have always been independent and vigorous. These symptoms are new and disturbing.”

I began to wonder whether, at my age and in my condition, I could continue my old seamanship practices. One of my habits was to take a walkabout and inspection tour of the deck and nearby fittings every two or three hours (of course, I was always hooked on with my safety harness). Once, in a deeply reefed 45-foot sloop slogging through the Gulf Stream toward Bermuda, my flashlight beam triggered a bright spark in the leeward waterway. Further inspection revealed it to be a cotter pin that had somehow fallen out of the headstay turnbuckle (where it was quickly reinstalled).

Would I do that inspection today? Surely not in rough weather. But I could train a younger sailor.

The most important piece of safety equipment in a boat is a healthy, fit sailor.

Circumstances of Concern

Concerned about my strength, endurance and mental acuity, I was quite sure that I had made the correct decision by dropping out of the delivery crew. Yet I had some doubts, and to test them I consulted the spirits of some great and thoughtful sailors who, each in his own way, had said something wise about seafaring in rough conditions.

Joseph Conrad, who spent the first half of his life at sea and then devoted the second half to writing about it, offered a pithy rule of thumb in his autobiography, The Mirror of the Sea. Conrad’s rule was this: “A seaman laboring under an undue sense of security becomes at once worth hardly half his salt.” The key word is undue. A sailor must be honest and frank about risks.

One observer of this rule was Olin Stephens, a great yacht designer (his boats include the one I was to sail in from Bermuda) who was a vastly experienced and successful skipper and navigator. A man of considerable reserve and modesty, he sometimes was quite bold in his sailing and his autobiography, All This and Sailing, Too, for which I provided editorial assistance. He had few fears on the water so long as he trusted the boat. “The hard push was the highlight for me,” he wrote of a wild Fastnet Race in England in 1931 in his yawl Dorade. “We were sailing fast, and I thought it was wonderful as I felt her roll, first with the main boom hitting the water, then with the spinnaker pole almost doing the same. I could hear the water coming in over the bow and rushing down the side deck, moving fast, much of it over the cabin trunk and companionway. It sounded a little like Niagara Falls.” His shipmates worried, but Olin knew the boat was doing what he had designed it to do. Fifty years later, at age 72, he retired from both work and serious racing.

Forehanded

This notion of preparing well for any challenging activity has recently been renamed “forehandedness.” A surgeon, Christopher Nemeth, has defined it this way: “Anticipation and preparation for the uncertain future so that we are ready for it by the time it becomes the present. Forehandedness enables us to achieve a robust performance that can make success possible in spite of circumstances.”

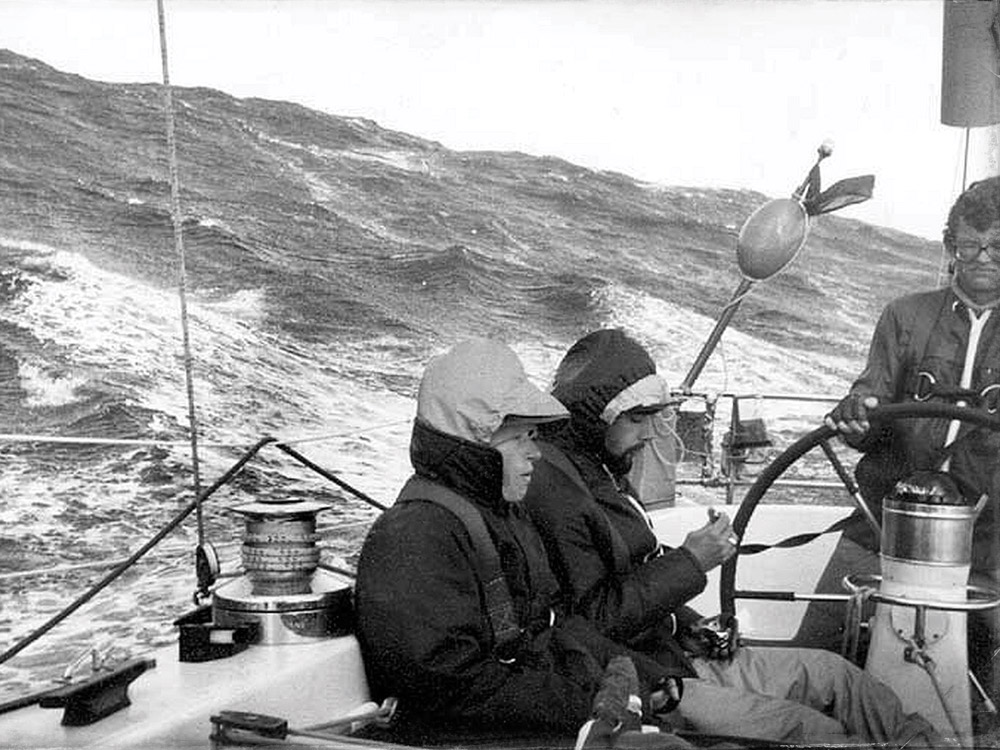

“Circumstances” can vary, but if there is one place where they are constantly under consideration, it is in a sailboat banging across the mighty Gulf Stream, with great swirls of rapid warm-water currents bashing against each other and the strong winds that often blow. Of my 25-plus Stream crossings, at least half have been difficult. In one, a 65-knot gust blew the inner forestay right off the boat. During my first Stream crossing, as a 19-year-old deckhand on a big ketch headed to Greece, we were obliged by a northerly gale and the huge breaking sea it stirred up to heave-to for a day under a storm trysail. We couldn’t set that essential little sail until the deckhand spent the afternoon reattaching the sail slides that had fallen off because their seizings had rotted away.

This memory reminds me of some Gulf Stream wisdom written by the brilliant boating journalist Alfred F. Loomis: “A man who can’t stand the Stream blues is no addition to a crew, however ornamental he may be to a bar.”

Stamina

My own contributions to pithy seamanship rules include this statement in my sailing manual, The Annapolis Book of Seamanship: “The most important piece of safety equipment in a boat is a healthy, fit sailor.” My point is that many sailors place too much faith in the safety hardware they buy, and not enough in the skills, leadership and good judgment of the sailors they sign on as crew.

But there is another issue that strikes to the heart of my personal concern. That is physical fitness. Cruising World’s Herb McCormick raised this issue in his book As Long as It’s Fun, his fine biography of the remarkable Pardeys, Lin and Larry. Builders, owners and only crew of the famous Taleisin, they have retired from voyaging due to advancing age and health concerns. Lin told Herb, “I’m finding it difficult to right out say, ‘I’m not sailing across any more oceans with Larry,’ but he’s made it pretty clear that he doesn’t feel he has the stamina to handle emergency situations. So why be out there?” In other words, when voyaging is not all that much fun anymore, you don’t have to do it.

Reflecting on these risks and variables, and the related morale issues, I think of a story about Sir Edmund Hillary. Long after he conquered Everest, he was not having much fun at all on a long, slow, discouraging slog across Antarctica. As he lay tossing in his sleeping bag, nagged by his faltering confidence, he took careful, objective inventory of his aptitudes and came up with this: “Slightly crazy, frequently terrified and not a bad navigator — and that about summed it up.”

Reassured of his fundamental competence, Hillary rolled over and slept like a baby. He had in his humble way succeeded in converting unhealthy fear into constructive caution. Knowing when to take a step back or even give in is a measure of wisdom and maturity. We can survive the important sacrifices.

John Rousmaniere is a longtime sailor and Safety at Sea instructor, and author of many sailing books, including Fastnet, Force 10.