There are countless stories about yachts abandoned at sea because they lost their steering or rudder. It’s a possible contingency that should be anticipated before heading offshore. Boats that have wheel steering should be equipped with an emergency tiller that has been tested and works. Too many emergency tillers are useless. Test your emergency tiller in heavy air, not only sailing to windward, but also on a broad reach and dead downwind, two points of sail that require a lot of steering.

Tiller Tales

The inadequacy of emergency tillers was brought home to me early in my career as a delivery skipper. I was delivering a 40-foot sloop, with a short keel but an attached rudder, from Grenada to Fort Lauderdale via St. Thomas, U.S. Virgin Islands. About 50 miles west of San Juan, Puerto Rico, the hydraulic-steering system packed up so we were forced to use emergency steering to San Salvador, in the Bahamas the first island we figured we could find a harbor.

We installed the emergency tiller, but it was not well designed. It was simply not strong enough and collapsed after about five hours. I found that the biggest socket in the socket set would fit on the rudder head, and a block and tackle on the wrench handle led to a winch gave us enough control to sail her 400 miles to San Salvador Island where we stopped and rebuilt the emergency tiller. Sometimes you need to go with what you got.

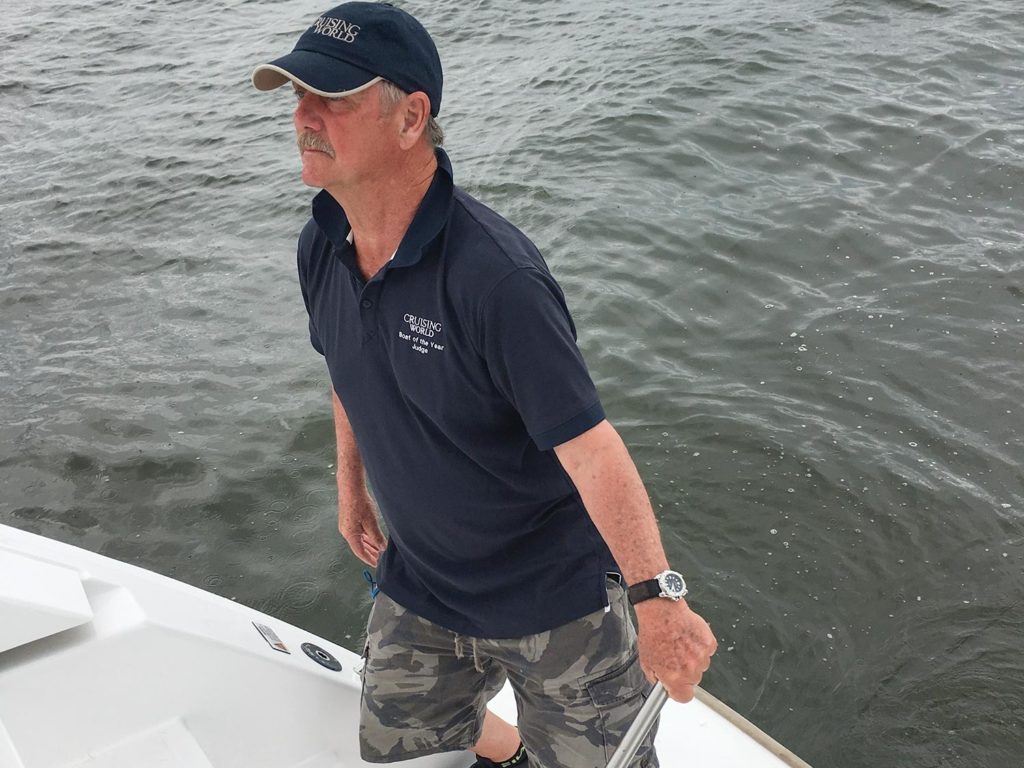

Contrast that to the tale of Pixie, a 54-foot Gardner-designed, ketch-rigged motorsailer. We were on another delivery, from St. Croix to Fort Lauderdale, when on the second day out once again the hydraulic steering failed. But it was no problem as Gardner had designed a proper emergency tiller. Pixie had a center cockpit and a large after deck. We simply undid a deck plate, moved a cushion in the aft-cabin bunk, dropped the emergency tiller through the deck plate onto the rudder head, and we were all set. As the tiller was a full 6 feet long, we had plenty of leverage. As seen in the accompanying photos from the 2019 Boat of the Year tests, many contemporary production cruisers have emergency tillers as well thought out as Pixie‘s.

One common problem, particularly with many older vessels, is that many extended emergency tillers are designed to pass over the top of the wheel. This arrangement may look good on paper, but when you try to use it in heavy weather, especially going downwind, it doesn’t work. The problem is that the tiller must have some height to clear the wheel, but because of its accompanying short lever arm, there’s not enough torque or leverage for it to be effective.

Contemporary yachts, of course, are very beamy and they carry that beam well aft, which means extremely wide sterns. I think many designers are missing an opportunity on these boats to create a better emergency tiller. Because they’re so wide, why not employ a T-shaped tiller? (There were examples of T-shaped emergency tillers in the Boat of the Year testing, but I’m thinking about one that would extend farther abeam.) It would be easier to fabricate with a longer lever arm extended port and starboard. If control was an issue, two people could steer, one to either side. You’d probably want the “arms” of the T to be easily removable for storage. One thing you already see on some modern boats is an emergency tiller pointed abaft the rudder head. This solves the problem of conflicting with the wheel and pedestal.

On cable-steering systems, the most common failure, naturally, is broken cables. Replacing steering cables at sea is difficult, but not impossible. Superyacht skipper Billy Porter told me a story with advice useful to any cruiser. Porter was a veteran of the Royal Navy who crewed aboard a yacht in a round-the-world race that entered as part of the service’s sail-training program. The crew figured sometime in the Southern Ocean, after thousands of miles of downwind sailing, a steering cable would break and they’d lose steering. When that happened, they planned to round up, drop the spinnaker, hoist the staysail and trim the boat so it hove to. Then they could make repairs.

Halfway to Cape Horn, that exact scenario unfolded. The crewman designated to steering controls — everyone had a specific duty — dove down below to address the problem. The rest of the crew reckoned it would take hours to do the job. But 20 minutes later, the crewman popped out of the hatch and said, “New cable installed and tensioned, get underway.” Everyone was amazed and asked how he did it so quickly. It turned out that during his time in port, he stayed aboard and set his alarm for midnight each night to practice changing a cable. The first time took three hours, but he soon learned to assemble all the required tools and different lengths of spare cables near the lazarette. Each night he got quicker and more efficient, so when there actually was an emergency, he was ready. The point is, for those heading offshore, it’s worthwhile to try replacing a steering cable in port — before setting out.

Lost Rudders

Another common characteristic of modern designs is spade rudders. Again, in recent times we’ve heard too many stories of crews abandoning boats in midocean because they completely lost a rudder that either dropped because of a structural issue or because it hit something. Scanmar International is one of the few companies that builds dedicated emergency rudders. The firm’s M-Rud unit works in conjunction with its Monitor windvane, and its SOS Emergency rudder is a stand-alone system worth investigating.

If you do lose a rudder, and you are not carrying a specific emergency rudder, my advice is not to waste any time trying to rig a spinnaker pole with a door secured to it as a rudder. I have heard and read about dozens of sailors who have tried this rig, and it simply does not work.

A more successful tactic was employed by the crew of the Dutch 55-footer Olivier van Noort in the 1953 Fastnet Race. After rounding Fastnet Rock, the boat lost its rudder. The crew responded by rigging a spinnaker pole across the deck and running lines through blocks secured to the ends of the pole’s port- and starboard-side that were attached to a drogue streamed astern. With the lines led to winches, the crew was able to manipulate the drogue to steer the boat.

I’ve heard a similar story from yacht designer Bill Tripp, who was aboard one of his own 60-footers when it lost a rudder on a race 60 miles north of Nassau, Bahamas. That crew didn’t use a spinnaker pole, but they did deploy a drogue that was “triangulated” by lines led directly to winches. In a northerly breeze, they had some success, but ultimately were more successful after setting a staysail (with no main). The drogue kept the stern directly behind the bow, and the crew was able to fine-tune their course by trimming the staysail to control the direction of the bow. And they made it safely to Nassau.

Likewise, the Rhode Island-based Keyworth brothers, Mike and Ken, have been able to tightly control the Swan 44, Chasseur — also without a wheel or rudder — by employing a 30-inch Galerider storm drogue with a double-reefed main and just enough of the genoa unfurled to fill the foretriangle. To rig their drogue, the Keyworths led spinnaker lines from the drogue forward to a pair of snatch blocks set amidships, then aft to cockpit winches. In all these cases, there was a lot of experimentation with sails and line placement for the drogues before finding a workable solution. But solutions were found.

Never underestimate the option of just using your sails if the breeze is favorable. With the wind abeam or forward of abeam, depending on the vessel, many good sailors can steer a boat using sails alone. Yes, it’s easier on a ketch or yawl, which have more options, than it is on a sloop or cutter, but it’s possible with any rig. That said, a cutter with a staysail as well as a jib is easier to steer under sail alone than a single-headsail sloop. Once the wind goes abaft the beam, it’s time to switch to the drogue.

To sum up, for resourceful sailors, a loss of steering or a rudder should not necessarily be regarded as a complete disaster. If well prepared, with well-practiced routines and the proper gear onboard, they could just be a major inconvenience!

Don Street is a legendary sailor, author and voyager, and a frequent contributor to Cruising World. His seminal book, The Ocean Sailing Yacht (volumes 1 and 2), was originally published in 1974 but remains a valuable resource to this day, and can be ordered online from Amazon and other outlets.