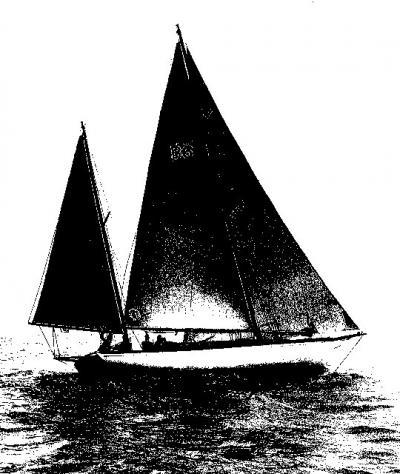

crw0413_lands-end.jpg

In 1946, Mary Paul “Paulie” Loomis spent her honeymoon sailing for four months aboard the ketch _Land’s End_ in Alaska. She cursed at hefty brown bears who interrupted her foraging for blueberries, caught salmon, and climbed the mainmast like a monkey to perch in the spreaders, alert for rock and reef. It was a pretty brave foray in a time when the waters of that vast territory weren’t charted to a modern standard.

The 22-year-old was from the MacLeod family of Philadelphia’s Main Line. Her newlywed husband, Henry Loomis, hailed from one of the wealthiest, best educated, and most influential families in America. His scientist father, Alfred Lee Loomis, helped develop radar and invented the long-range navigation system known to sailors as LORAN, and Henry, as a lieutenant commander in the U.S. Navy, trained pilots in its use during World War II. This is but a smidge of the countless, lofty Loomis family accomplishments over the 1900s in science, government, and business.

The Loomises also loved to sail. Alfred Lee put up the money, and Henry had the mahogany-planked, oak-framed_ Land’s End_, designed by Sam Crocker and built by Britt Brothers in Lynn, Massachusetts, completed for himself and his brother, Alfred Lee Jr., in 1935. Lee, as Henry’s brother was known, went on to became a financier and an Olympic sailor who also managed the successful Independence-Courageous America’s Cup syndicate in 1977. Not only was Land’s End a platform for nautical exploits; she also once came in handy for science: The senior Alfred Lee had an interest in brainwave research, and for one experiment into hypnotic suggestion, an investigation into the impact of emotional disturbances on brainwave activity, he whispered into a sleeping Henry’s ear that Land’s End was on fire.

Like Crocker’s other trademark designs, Land’s End was sturdy, rugged, and simple, with a plumb bow, a bowsprit, a boomkin, and yards and yards of canvas, including a squaresail. Below, the boat’s amenities were basic yet comfortable. An icebox that was loaded from the deck could carry up to 550 pounds of ice; coal was routed through a scuttle to a locker beneath the Shipmate cook stove. The nav station was amidships, opposite the head; the saloon contained a varnished dining table and was made cozier thanks to a Wilcox Crittenden blue ceramic fireplace, trimmed with bronze edging, a Delft tile of a Dutch sailing barge as its centerpiece over the hearth. A forward cabin contained single bunks with mahogany leeboards.

The brothers loved sailing the boat and raced it in the 1936 Newport-Bermuda Race, voyaged to Labrador and circumnavigated Newfoundland, then shipped the boat to Seattle.

And that’s where Paulie—who, as a 19-year-old, was one of the youngest members of the Women Airforce Service Pilots but didn’t know how to sail—enters the story. After a familiar wartime pattern, a young Paulie met a young Henry in San Francisco when he was on shore leave from the USS Enterprise aircraft carrier. Perhaps he was drawn to her youthful beauty, her independent thinking, or her spunk. Maybe her prowess as a horsewoman, skier, hunter, tennis player, and fisherwoman drew him in.

But surely her achievements as a pilot bowled him over: Paulie was one of only 1,074 women to fly in service to the U.S. World War II military effort. Of the 104 women in her class, designated 44-W-3, only 56 graduated. Paulie herself test-flew the dangerous B-26 and the light Cessna 78, one of which she landed without a hitch when the engines gave out right after takeoff.

The romance blossomed into marriage. Brother Lee sold his share in Land’s End and gave it to Henry and Paulie as a wedding gift. Off they went.

“I love Land’s End,” Paulie told me in the summer of 2012 when I met her on a remarkable day aboard the boat after the 46th-annual S.S. Crocker Memorial Race in Manchester by the Sea, Massachusetts. “But I thought she’d been cut up and sunk. I thought I’d lost her forever.”

She wasn’t exaggerating her feelings; her love for the ketch was evident.

But what was it exactly that Paulie and countless other sailors have so clearly known and felt so deeply about_ Land’s End_? What was it that I—after nearly 15 years of supportive yet somewhat passive immersion in the life of this boat—still stubbornly didn’t get about her?

Perhaps, I thought as I sat down to chat with the woman who’d pioneered the role that I now play on Land’s End, the opportunity for understanding what had been invisible to me was at hand.

PAULIE’S RIGHT ON ONE COUNT: She did lose Land’s End, when she and Henry divorced in 1974 and he took the boat to Maine. But many happy years interceded. Career opportunities for Henry at MIT called; the couple moved back to the U.S. East Coast, buying a home on a tiny island lying practically midchannel in the harbor at Manchester. They had four children. All of the Loomises—family and a wide net of friends—cruised and raced spring through fall aboard Land’s End, which was brought back East and kept on a mooring by the boathouse at the island.

The boys loved diving off the spreaders; a daughter, Pixie, who’d grow up to be an equestrienne, loved riding the staysail until Henry would shoo her away so he could raise it. The family spent a Thanksgiving or two aboard the boat at Jeffreys Ledge, off the Massachusetts coast; they roasted turkey, although usually the onboard fare was a pretty spare matter.

As the kids became teenagers, they’d take off alone aboard her. Somebody was always getting into mischief; groundings weren’t unusual, but the boat could take it. Over the years, in her steady, comfortable way, Land’s End touched dozens of lives, and today, a number of people carry vivid memories of her.

But on the other count—the rumors of sinking and demolition—Paulie, to her own endless delight and that of family and friends, is blessedly wrong.

So far, the ketch has had three owners: the Loomises, then Bob Booth, who bought the boat from Henry in the 1990s and kept her in Rhode Island to teach sail training.

The third, and current owner, is Captain Rick Martell, my other half, who found Land’s End at a yard off Rhode Island’s Sakonnet River in a pretty sorry state, although intact and complete with all tackle. Over my vigorous objections, Rick bought her in 1999.

“It’s the boat I’ve wanted to own all my life!” was his battle cry.

My forces were swiftly routed. Nose in the air and not all fingers in the pie, I cursed Booth for the gross interior left behind, the bulkheads painted turquoise, the scratchy settees laden with cat hair. And I wasn’t nuts about miles of teak and mahogany, leaks and mold, belaying pins, or a boomkin.

UNDETERRED BY HIS GRUMBLING and whiny first mate, my good captain, a Renaissance man of sorts—VietNam vet, potter and artist, logger, professional skipper and delivery captain—set off on a mammoth project over the next dozen years to refurbish the love of his life.

Today, though pretty much as she was when Henry had her built, Land’s End carries a new main, jib, and mizzen sail and roller furling; lazy jacks; varnished grabrails; a rebuilt samson post; a reconstructed transom that’s now varnished, not painted; a rebuilt Westerbeke marinized diesel; Lowrance radar and a chart plotter; and some new deck hardware, including a rounded varnished box that people think is the rum cask but is actually an attractive way to hide a propane tank. More recently, another 1,000 pounds of ballast have gone in to put her back on her lines and help balance her better under sail.

Belowdecks are more of the fruits of Rick’s hard labor, which he’s fit in between seasons of sailing various designs—from Oysters to Hinckleys and Swans—to and from the Caribbean for private owners. He installed, or had installed, new upgraded electrics, extra battery banks and a galvanic isolator, interior lighting, a redesigned galley with wood shelving, liner boards of mahogany above the lockers, and new cushions upholstered with jade-green Ultrasuede. He wooded, reefed, and caulked the hull. He ripped out the gross, spongy cork sole and had one of satin-surfaced pine boards installed. Rummaging around at marine consignment shops, Rick found a kerosene anchor light, which we suspend from the mizzen boom in the cockpit at night, and a hurricane lantern, which we use to warm the saloon. Last, but not least, he painstakingly removed the turquoise paint and refinished the interior with an eggshell white.

We did make one other small change that’s important to us. Working in what former CW editor Nim Marsh calls the Word Mines of_ Cruising World_, I’ve learned to appreciate the style requirements of the National Geographic atlas. Over the years Land’s End was spelled “Lands End,” without an apostrophe, and it didn’t make sense, if the reference was to England’s most southern point of land. So we made the change to “Land’s End,” and when Rick found an Olde Towne canvas-covered ribbed dinghy, we named her Lizard, for the opposing, smaller point of land.

Both are in decent enough form. Land’s End is still rough around the edges and needs way more TLC than our pocketbooks can afford; there’s nothing more costly, or non-essential, we know, than restoring and maintaining a classic wood ketch. In the 1980s, Brooklin Boat Yard in Maine had done a partial refit of Land’s End for Henry. But make no mistake—the boat is not a museum piece. Land’s End is no gleaming Herreshoff New York 40, 12-Meter, or S- or P-class charmer that wins the silver trophies on the wooden-boat regatta circuit. She’s an old boat, and she’s for relaxing.

She hasn’t been cut up, and she hasn’t sunk, and those are the most important things of all.

EARLY ON, IN SUMMER we’d explored a few Narragansett Bay anchorages , southeastern coastal Massachusetts, and Martha’s Vineyard. Cruising is for going places, I’d complain, not tinkering and varnishing. And the mold—sheesh!

Admittedly, it was a treat to bring Land’s End into a harbor: People buzzing around in their dinghies would sing out admiration for the classic wood ketch. When this happened, the sting over the amount of time and money she commanded in our lives would mingle momentarily with pride, which I had no business feeling, as this was Rick’s project, not mine. He’d only nod at my repeated critiques, and when people paid him compliments, he’d beam a brilliant smile.

Eventually, we converged with other owners of Crocker designs. Barry Blaisdell, the owner of Gabriel, a Crocker sloop, contacted us and invited us to do the annual race in 2001. (See “From Land’s End to the Crocker Cult,” in CW July 2002.) Sailed on a triangular, windward-leeward course of about 20 miles, the race is one of the larger summer sailing events in New England and has drawn up to 100 boats in dozens of current and classic-plastic designs, from Catalinas to Tartans, Bristols to Sabres, Pearsons to Hanses, Jeanneaus to Js.

__

Land’s End, we decided, wasn’t ready for a 100-mile transit from Rhode Island to the starting line that year, so we drove up and crewed with the Blaisdells, and Gabriel won. At the post-race party at Crocker’s Boat Yard, we met Sam’s son Sturgis, his son, Sam, and Sam’s son, Skip. People were thrilled to learn that Land’s End indeed was afloat. “You’ve got to bring her up to do the race,” they told us. “You have to.”

THE FRONT PAGE of The Manchester Cricket, an independent weekly newspaper, offers up the usual small-town fodder writ large. And the front-page feature in the issue of June 22, 2012, was no different, unless you happened to be a now-88-year-old woman named Paulie Loomis or the man whom Loomis didn’t know: Rick Martell.

“Lands’ End Featured for 46th Annual S.S. Crocker Race” read the headline, with yet another variation of the possessive apostrophe.

“Each year the Crocker Race is dedicated to the memory of S.S. Crocker and the boats he designed,” begins the article by Carrie Woodruff. “This year’s featured boat is the Lands’ End, built in 1935 for Lee and Henry Loomis.”

Paulie called Skip. “I want the owner’s phone number!” she demanded.

Skip assured her that he’d pass on her contact details, then contacted Rick. “Are you still coming?” he asked. “We’ve put your lines drawing on the glasses we give out after the race. We’ll give you a mooring for as long as you need it and put you on the dock of the Manchester Yacht Club for the party. And the wife of the original owner wants to speak to you.”

The heat was on; we were committed. Rick went into delivery mode, plotting a 100-mile course from Newport, Rhode Island, to Manchester, buying food, and loading pounds of block ice into the box—yes, through the deck. Before he left, he called Paulie.

“Who’s this?” she said. “Wimbledon’s on.”

“It’s Rick Martell, Mrs. Loomis,” he said. “I’m the owner of Land’s End, and Skip Crocker said you wanted to talk to me.”

“Land’s End?” she exclaimed. “I love that boat. I need to see it again!”

THE REUNION OF PAULIE and her beloved boat was enormously significant for me. It was an event that in my mind, in retrospect, eclipsed the race itself on July 14, although that, too, was a weighty achievement for Land’s End—and a ton of fun for all the crews of the 60-boat fleet, which included a total of four Crocker designs. Post race, we tied up at the slip at the Manchester Yacht Club as the belle of the ball; we lay next to Tyrone, a 60-foot Crocker whose owner, Matt Sutphen, had embarked on a love affair similar to Rick’s in 2006, when he bought the schooner. A stream of admirers, well-wishers, and former crewmembers who’d sailed on Land’s End came aboard, and the captain wore the grin of a man who’d won a billion-dollar lottery. “Overwhelmed” is about the only word that describes the state of the first mate, who’d presided over a rushed and frenzied session of polishing and cleaning, air-freshening and rearranging.

Any less of an effort was unthinkable on a day that more than a dozen years ago would have been simply unfathomable.

“This is just great!” Paulie burst out as Rick reached over and helped her climb aboard. “She hasn’t changed a bit!”

Of course not, I thought, but I behaved, buttoned my lip, then scurried past her belowdecks so I could take in her reactions when she saw the interior.

Slowly, steadily, knowingly, Paulie descended the steep companionway stairs, turned toward me in the saloon, and, with an amazed and half-dazed look on her face, ran her hands over the liner boards as she moved forward. Then she kissed the kerosene lantern above the nav station.

“This is just great!” she said again. “Henry would’ve loved to see this.” She settled onto a settee cushion, and Rick came below just in time to hear her begin reminiscing. Memories poured out of her like milk from a pitcher. No stone was left unturned; she recalled the 24 snatch blocks that went with the square sail, the challenge of heaving to, how she and Henry traded watch duties, how the boat originally had no forward hatch, where she had dish drying racks installed so she could clean up and set drinks out. Looking down, she said, “The cork sole was so greasy. This is so much better.”

My jaw tightened; goose bumps popped up on my arms. This woman really remembers this boat. Really.

She went on. During their Alaska honeymoon cruise, they were running low on ice as they came into Nanaimo, on Vancouver Island.

“We got there and asked if we could get some ice,” Paulie said. “Henry had grown this beard. He was a good-looking man. The guy on the dock said he’d sell us 150 pounds. I said, ‘150 pounds isn’t going to take us anywhere.’

“ ‘OK,’ he said. ‘I’ll give you 500 pounds, because your husband looks so much like Jesus Christ.’ I nearly fell over!”

While Paulie and Rick chatted on about sailing, the Loomis family, and the boat’s years in Manchester, my mind was racing. There were things I still wanted to know; gaps in the tale nagged at me. I needed to settle at least one of them. She’d told Rick during their phone call that she’d spent her honeymoon aboard the boat, whose forward cabin contains only single bunks.

I interrupted them. “While you cruised in Alaska,” I said, “You say you slept in—?”

“We slept here, in the saloon,” she answered without missing a beat. She grabbed the slat that I’d forgotten about, the one just beneath the starboard settee, and gave it a tug inboard.

“I had this made into a double,” she said. “It was so warm and cozy with the fireplace. Don’t ever lose that,” she said, emphatically pointing at the fireplace. “It’s a treasure.”

| |JOIN the 50th S.S.Crocker Memorial Race: While our participation in the 46th race in memory of naval architect Sam Crocker was a milestone for Land’s End, the highly popular and well attended event comes off like clockwork every July. Anticipation is now building for the 50th celebration, set for 2016. Send your ideas for a fitting tribute to both Crocker designs and half a century of the regatta to the president of Crocker’s Boat Yard, Skip Crocker ().|

And that was my instant of clarity. It all made sense to me now, Paulie Loomis aboard Land’s End, in 1946, in Alaska, on her honeymoon. With her fortune and her imagination and her drive, she could have placed herself at any one of the beautiful or elegant places that the world conjures up for pleasure. Instead, she chose to court rough-hewn adventure on Land’s End. In Paulie Loomis endures the spirit and truth about Land’s End, a saga of living life to the fullest that I’d ignored all these years, too focused, I now see, on mold and miles of varnish.

So, as I’d done countless times before—always immersed in all my senses, but with the feeling on those occasions that there was much more to this boat than I could ever know—I scanned the saloon and its contents: simple kerosene lamps, varnished lockers, wooden ceiling ribs painted eggshell white, the dining table, the blue ceramic hearth. I listened, and at last, I heard.

For the woman who so loved the outdoors, who was endowed with a trail-blazing spirit, who was a brave pilot towing live targets in war time, who wasn’t a sailor but had a few bucks, drove across America, met and fell in love with a man from one of the country’s more prominent, fearless, and patriotic 20th-century families, Land’s End made perfect sense. And it still does.

Elaine Lembo is CW‘s deputy editor.