Lying on my back, the lower half of my body on the aft end of the starboard pipe quarter berth, the upper half scrunched against the inside of my Moore 24 Gannet‘s hull, I could not quite see the bolts that were my objective.

Gannet‘s interior is a crawl space. Except in my favored position in a Sport-a-Seat on the two 7-inch-wide, 4-foot-long boards that pose as the cabin sole, I don’t have even full headroom for sitting (only slouching). So going aft on the pipe berths is more slithering than crawling. Slither I did one morning in order to replace the Autohelm electrical deck connection with one made by Perko. I have two different tiller pilots: one from Autohelm, another from Signet. Installing Perko plugs on both now enables me to use them interchangeably.

Two tiny bolts, with two tinier nuts, secured the Autohelm fitting at the aft end of the cockpit. Reaching up blindly — something at which I am becoming increasingly adept — in a contortion no old man should have to endure, I finally fumbled a pair of Vise-Grips around one of the nuts and then rolled over and slithered backward on my belly to the companionway, went on deck, and unscrewed the bolt.

I never did secure the second elusive nut, and finally broke away enough of the plastic fitting from the cockpit side to expose its bolt to a hack saw. Why is it that when you are trying to remove something, with no matter how many or how few screws or nuts, one sticks?

I’ve been known to become a bit testy at such times. But that day I found myself thinking: It’s a lovely morning. You are on the water. You have nothing better to do than work on this boat, with the exception of sailing her. And that will come again with time.

Although I have owned boats for almost 50 years and probably shouldn’t have been surprised, I was — by how much time and money it took to convert Gannet, well equipped for round-the-buoys day racing when I bought her, into an ocean passagemaker.

Why anyone would want to do that is a reasonable question.

My initial plan was to buy a small boat to sail on Lake Michigan during the northern summer and fly to New Zealand, where my other boat, The Hawke of Tuonela, lived on a mooring, to sail her in the northern winter. Sounds pretty good. But from the beginning one of the attractions, for me, of Moore 24s was their reputation for liking big wind and waves; another was that many have been successfully raced from California to Hawaii. I like sailing oceans. I like being far away from land and settling into the routine of a long passage.

Several other factors entered in.

I have completed five circumnavigations over four successive decades — two in this century — and I’d like to make a fifth decade. I turned 70 in 2011, and going around again in my 70s is also appealing. But once I bought Gannet I realized, for me, that two boats are too many.

I have long known that I am a serial, not a parallel, machine. In other words, I concentrate on one thing and then go on to the next. I don’t like to multitask and have never thought that anyone does so well. Two boats more than 8,000 miles apart — plus a wife — were too much. Unable to do justice to both — plus a wife — I realized that I had to choose between them. Gannet won out because she offers the possibility of a new sailing experience, fresh challenges and more interesting problems to solve. Plus, I have a special affection for small boats.

Once The Hawke was listed for sale, Gannet‘s days on the Great Lakes were destined to be few. The Chicago area is the first place I’ve lived as an adult where you can’t even keep a boat in the water year-round. And I need the ocean’s endless horizon. So: a Moore 24 for the world. I have quoted from T.S. Eliot’s Four Quartets before: “Old men should be explorers.”

But preparing Gannet was taking such a long time.

The morning I changed the Autohelm fitting I had owned the tiny sloop just over a year. Yet by a more relevant measurement, I had owned her only three or four months. Bad weather prevented the boatyard from launching her until late May 2011, and a detached retina ended an already brief sailing season for me in early September. For a year, progress would be considered slow. For three months, it was pretty good.

My first major change to the boat was to replace her gasoline outboard with an electric Torqeedo. Then, after a few day sails, I started on her interior.

I doubt that many Moore 24 owners spend much time below. The boats are usually raced hard for a few hours and then put away, often on a trailer. Gannet‘s previous owner had told me the interior needed work, and he was right. Mismatched paint, dead cushions, a split in the vinyl on one of the pipe quarter berths, confused wiring: I needed to sort all that out before I could stay aboard overnight and have an organized base on which to build.

New cushions and pipe berth covers ordered, I removed everything else from the interior and painted it using Pettit’s one-part Easypoxy, from bilge to overhead. Moore 24s have no liner, which made this easier, though that is not a word that came to mind when I was sprawled roller in hand in that dead space in the stern.

With the paint dry, I sanded flaking varnish from the Bruynzeel plywood main bulkhead (with its distinctive circular cutout), and also from some other plywood panels. I also filled some holes and applied several coats of Deks Olje — I stopped varnishing decades ago. When the new cushions and covers were delivered, the transformation was dramatic.

The electrical system was next.

As one would expect with ultralights, weight is critical on Moore 24s, which displace only 2,050 pounds, half of which is in the keel. But the little boats are often raced with a crew of four or even five. The maximum permitted crew weight is 825 pounds, which put me 670 pounds ahead. While crew weight is movable and useful on the rail when going to windward, I intended to try to keep as much as I could centered and low. However, I was also thinking in terms of living aboard for months and covering thousands of miles, not spending a handful of hours racing dozens of miles (or less). So some compromise was inevitable. There was also the matter of style: Despite the weight, Gannet would carry a couple of Dartington crystal double old-fashioned glasses and a bottle of Laphroaig.

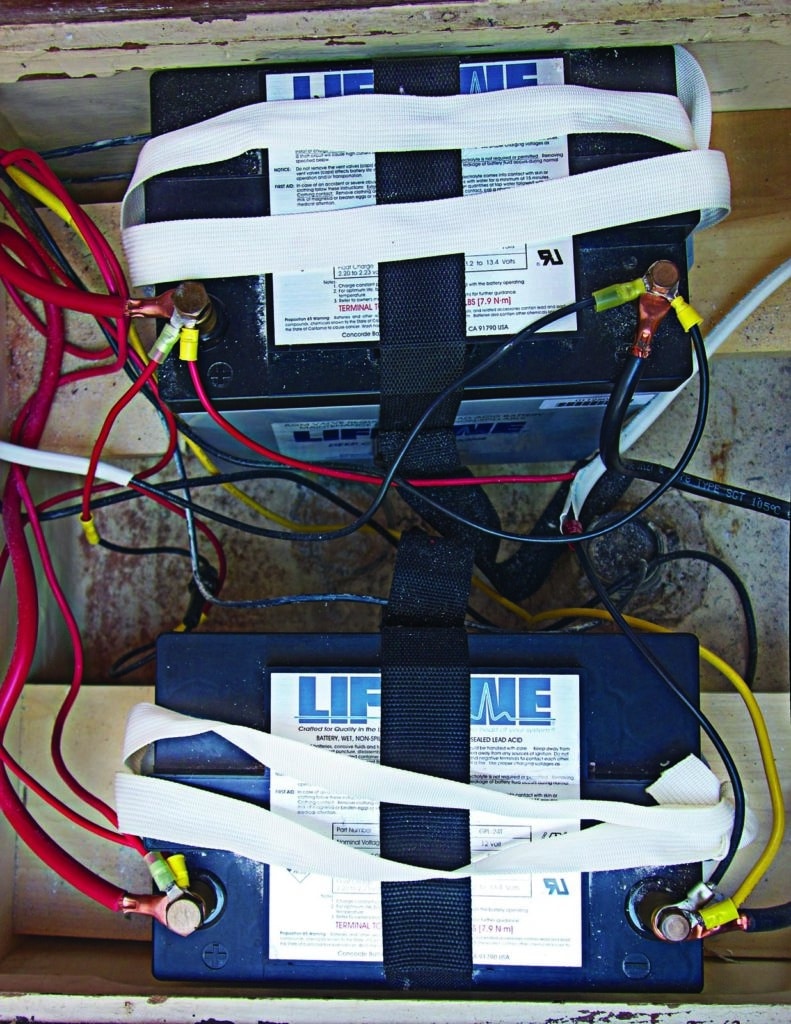

The first and greatest weight was a pair of 80-amp Group 24 AGM batteries, which just squeezed into the battery compartment at the aft end of the V-berth. At 56 pounds each, they were like always having another small person on board, though denser and located just above the keel. I replaced the fused electrical panel with one with circuit breakers; removed the single fixed cabin light and a wire running to a GPS antenna mounted on the stern; and secured other dangling wires.

Moore 24s are basically empty shells. There are no water tanks, head, sink or lockers, and to use the word “system” to describe her electronics may be an exaggeration. Gannet‘s batteries would be charged by solar panels that would in turn charge other batteries for computers, iPods and speakers; rechargeable Sanyo Eneloops, which I have found to be the only kind that hold their charge well during storage and remain ready when you need them; and the lithium-ion Torqeedo battery.

For charging I wired a cigarette-lighter socket directly from the AGMs to each side of the cabin, each with its own in-line circuit breaker. I then purchased from Amazon two Elgato Micro USB plugs, two Tripp Lite 150-watt inverters, two Eneloop chargers, and a lot of AA and AAA Eneloop batteries. Equipment charged with a USB cable is plugged into the Elgato. Gear charged from AC is plugged into the Tripp Lite, which I have found to be blessedly silent. Many inverters aren’t.

Music is essential to my sailing life. Gannet‘s system is appropriately ultralight, consisting of an iTouch and several Bluetooth speakers, including a Soundmatters FoxL v2 that is not much bigger than a candy bar, and a Bose SoundLink. The latter, which came onto the market after I had bought the FoxL, has fuller sound, but the FoxL is amazingly good for its diminutive size. It has long been my policy to have a backup for essential systems.

When I bought her, Gannet‘s depth finder and GPS displays were mounted on the mast and difficult to see. I moved the depth finder back to the cockpit, where a hole exactly its size, covered with a piece of plastic, proved it had resided there before. I also replaced the outdated GPS with a Velocitek ProStart, also mast-mounted, but with a very readable simultaneous display of GPS-generated COG and SOG.

Gannet‘s cabin lights are two Mighty Bright XtraFlex LED book lights, which have two levels of brightness and can be clipped anywhere. One is more than enough to illuminate what I like to call Gannet‘s “Great Cabin.”

When I installed the six-switch circuit-breaker panel, I labeled one “Chart Plotter,” but a timely article in Practical Sailor comparing chart-plotting software for iPads persuaded me to buy an iPad and the iNavX app instead of a conventional chart plotter.

Because there is some confusion about whether the iPad’s “assisted GPS” will record a position in mid-ocean, I also bought a Dual Electronics XGPS 150A Bluetooth GPS receiver, which may not have been necessary. I have been told that the latest iPads and iPhones will get positions anywhere, but I do not personally know that for a fact and do not want to find out a couple of hundred miles offshore.

With one caveat, I have found the iPad and iNavX to make an excellent chart plotter. iNavX is simple to understand and use; it comes set up to download all the free NOAA charts and also to access and purchase for reasonable prices charts for other parts of the world. So it does everything I need and a good deal more, like interfacing with NMEA 0183 and 2000, and even wirelessly controlling some autopilots. The caveat is that I find the iPad screen impossible to read in bright sunlight. This is not a serious problem because the unit is able to obtain a GPS position from inside the cabin.

Pairing the Dual XGPS receiver with the iPad was simple. But then I wondered how to determine if the position on my iPad was coming from its own internal antenna or the Dual.

Online I found advice on how to put the iPad into airplane mode, which turns off both the GPS and Bluetooth, and then to turn Bluetooth back on. When I switch the Dual on and off, the position appears and then disappears, which proves that the position displayed on the iPad is coming from the Dual. (I will probably eventually use the now free circuit-breaker switch for a masthead LED tricolor nav light.)

I also have chart-plotting software with detailed world chart coverage enabling my laptops to obtain positions using any of several handheld GPS units. And I bought a used David White sextant, the same U.S. Navy model from World War II that I used on my first circumnavigation. One way or the other, I should always know where I am.

Five-time circumnavigator Webb Chiles is a frequent contributor to Cruising World.