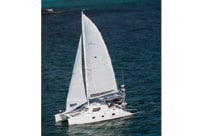

A rare sight on the world’s waters 20 years ago, catamarans are now ubiquitous. At boat shows, they elbow aside monohulls, clamoring for attention. And they get it. Their mere presence demands it. They’re big and brash, they offer bountiful creature comforts, and they revel in their exuberant styling.

Catamarans have evolved over the past three decades, and the public perception of the cruising cat has gone from oddball and dubious to mature and proven. Viewed more clearly through the lens of experience, the spectacular flips of some early racing models are accepted now as the inevitable outcome of experimentation and the price of progress. Modern cats have benefited from the “oops” moments of these pioneers, and they’re now considered at least as safe as monohulls.

“The first question out of the mouths of visitors aboard catamarans isn’t ‘Will it tip over?'” says Hugh Murray, president of The Catamaran Company, which handles cats in every capacity, from new- boat dealer to used-boat broker to charter broker. “We haven’t really heard that for five, maybe more years. We do get ‘How fast can it go?’ But that’s usually for pass-along information intended for the guys back at the office. What people are really interested in is the space.”

That, and the idea that sailing holidays don’t have to mean the family has to be cramped together, white-knuckled, at 30 degrees of heel. Instead, they can spread out and lounge in the airy deck-level saloon, with its wide view of the horizon; engage in the sailing in the roomy cockpit; or lie on the trampoline and watch the sea go by.

The most popular cats bear out this dynamic. Their predominant features are an abundance of living space aboard a stable platform. Despite the inherent potential in the configuration, cruising catamarans, just like cruising monohulls, aren’t built for speed but for comfort. Their appeal has as much, if not more, to do with the luxury they offer–and a penchant for lying quietly to an anchor in a rolly roadstead–as it does with their ability to sail a little faster off the wind than their monohull cousins. OK, in some cases, a lot faster.

While cabin count and condo-like convenience rank high on the cat designer’s brief, they come blended with performance and seakeeping features in all ratios. There’s a cat for every wallet and want, from small to large and from gentle and domesticated to fast and feral.

Under 30 feet, a catamaran’s natural proportions converge to make it less habitable than a monohull of similar length. The hulls become constrictingly narrow, and it requires great artistry on the part of a designer to fit headroom into a bridgedeck saloon without seriously limiting clearance over the water or condemning the profile to a caricature.

One of the smaller boats with true liveaboard potential is the 33- foot Gemini 105Mc. It has accommodations approaching those of a 38- or 39-foot monohull–and at $150,000, not a dissimilar price. With centerboards raised and rudders tilted up, it can float in knee-deep water.

At 40 feet and over, available space seems to grow exponentially.

“These boats have more space than many two-bedroom apartments,” says Murray. “Buyers see them as a home away from home, and more and more they’re bringing household appliances aboard, like a flat-screen TV for every cabin.”

Still, the draw for some sailors remains the potential for exciting, wave-skimming passages. For them, such builders as Outremer and Maine Cat offer boats with more slender hulls and less capacity for weighty accoutrements.

“The Outremer 45 has as much performance as you’d want in a cruising cat,” says Gregor Tarjan, the president of Aeroyacht, a dealer for Outremer and Fountaine Pajot. “The trade-off is narrow hulls and low headroom.”

Compared with more sumptously appointed 40-footers, the slippery Maine Cat 41 is on a tighter budget for sleeping quarters, and it doesn’t even have a bridgedeck saloon. On the tween-hulls platform, it’s set up for open-air living under a fixed hardtop–a sun porch under sail.

As the number of new catamarans has proliferated, so too has the number of used boats. “In the early 1990s, there might have been under 100 used multihulls on the market, max,” says Bill Ware, co- founder of 2Hulls, which is now part of The Catamaran Company. “Today, we have over 170 listings, and that’s just The Catamaran Company. Worldwide, the number is much larger.” In early spring this year, his company listed half a dozen Lagoon 38s, which isn’t surprising given the builder was approaching hull number 400 in production. Their prices ranged from $225,000 to $325,000, an indication that cats from the recognized builders hold their prices well.

Over time, Ware has seen many different types of buyer. “Some sailors buy a cat as a transition boat,” he says. “Especially monohull sailors. They might be thinking of moving to a trawler later on, but they buy a cat because it’s stable, and they aren’t ready to give up the sails.”

Whatever your needs and preferences, and those of the others around you involved in the decision making, you’ll find a number of choices where your desires will mesh with what’s available.

**

Equations in Cat Design: Develop a critical eye for proportions**

Many factors determine how a cat functions, that is, how well it delivers its promise as a sailboat and as a living space. Designers go to great lengths to create the desired level of appointments while balancing hull hydrodynamics and weight distribution to provide the requisite combination of performance, stability, and ride characteristics.

As in monohull design, one goal is to keep weight close to the center of the vessel to reduce pitching. But if the weight is too concentrated, the pitch frequency may in fact become uncomfortably short. This won’t bother adrenaline junkies but might put the less sanguine on edge. Moving weight away from the center of gravity will lengthen the pitch frequency but also increase its amplitude. Too far, and the motion both tires the crew and slows the boat.

Hull design, particularly how finely the bows and sterns are drawn, also contributes to pitching characteristics. Full ends with generous reserve buoyancy will act quickly to damp the motion, perhaps uncomfortably so. Fine ends may not damp the pitching enough, resulting in hobbyhorsing and, perhaps, the potentially dangerous immersion of the bows. Fine ends work best on boats groomed for speed with centralized weight, whereas full ends better absorb the long- period pitching of a heavier boat with a more widely distributed load.

It follows that boats designed for the performance end of the spectrum have short bridgedecks that keep the weight centered; pure cruising boats spread the accommodations, and the load, more longitudinally. The bridgedeck of the built-for-speed Gunboat 48 is 53 percent of the boat’s overall length. On the Switch 51 and the Catana 47, it’s 55 percent. At the opposite extreme are the Gemini 105Mc (89 percent), some Lagoon models, and the Royal Cape Catamarans 50 (82 percent). Most cats fall between the Nautitech 40 (63 percent) and the Lagoon 420 (77 percent).

Another key factor in the agility-vs.-amenity equation is the length- to-beam ratio of the hulls at the waterline. Narrower hulls are faster but don’t have the payload capacity of beamier hulls. Most cruising-catamaran hulls have length-to-beam ratios of about 8:1, but at this ratio, even a 40-foot hull offers tight quarters, taxing the designer to create accommodations that aren’t claustrophobic. Ways of creating additional living space include flaring the hulls above the waterline or stepping them inward in way of the wingdeck. This sometimes results in increased drag when sailing in anything other than flat water.

Builders run the gamut from mass producers to one-at-a-time custom yards, and each weighs the features that affect performance, comfort, and cost, hoping to strike the balance that will attract the right customers in the right numbers. Clues as to the builder’s thinking are visible on the boat’s exterior.

If peppy performance is on your wish list, look for a bowsprit, used to project the tack of a cruising chute of some kind. Look also for daggerboards, which particularly improve windward performance and maneuverability. Windage is a big drag on cats, so boats designed for speed and agility tend to have a more streamlined appearance: rounded deck edges; smooth, lozenge-shaped deck saloons; lower total profile. Faster cats also have shorter bridgedecks, so eyeball the trampoline area forward and the hull extensions aft.

More cruiserly craft tend to have longer bridgedecks, as mentioned above, plus larger and squarer superstructures and simpler rigs. If you don’t want to hassle with daggerboards and will be content with less spectacular performance, go with fixed keels; depending on where you cruise, you can take advantage of their shallow draft when seeking isolated anchorages or pulling up near a beach.

If you’re a wind-in-the-face sailor, you might prefer dual helm stations out on the sterns over the more common position at the deckhouse bulkhead. Nautitech and Catana favor this approach, while Lagoon, on its larger models, has a flybridge, removing boathandling operations from the cockpit completely.

One of the most talked-about dimensions on catamarans, and one that you don’t often find in the published literature, is the wingdeck clearance–the height of the wingdeck or bridgedeck above the water. Slamming in a seaway can make offshore passages noisy and uncomfortable, and while factors like bow buoyancy and the shape of the tunnel also come into play, high wingdeck clearance is the single surest way to reduce the number of impacts in a given sea state. In boats intended for high-speed offshore voyaging, designers aim for as high a clearance as possible in keeping with goals for low weight and windage. Height isn’t so critical in boats intended for cruising in coastal or sheltered waters.

By making observations from the dock, you can get an idea of which boats might satisfy your sailing needs. Only then should you venture aboard–where you’ll surely be seduced by the sumptuous saloons.

**

Payload vs. Pace: Some designs handle the poundage better than others**

With a few exceptions–Prout catamarans came into existence before the age of fiberglass and of singlehanded transatlantic races–cats first entered the public’s awareness by sweeping the field in the ocean races in which they were allowed to compete with monohulls. But just as it’s a myth that catamarans are inherently unsafe, it’s also a myth that they’re all fast. They’re susceptible to the same performance constraints–poor hull design, too much weight, insufficient sail area, inefficient keels–as monohulls. And as with monohulls, only 10 times more so, every creature comfort you bring exacts its price from speed.

Catamarans are sensitive to loading in direct proportion to their projected performance. “You can add 10 percent to the weight of a monohull and lose maybe one percent of its maximum speed,” says Gregor Tarjan, Aeroyacht’s president. “Do that to a multihull and you lose 10 percent of speed.”

The narrow hulls of a fast boat will immerse more quickly than the wider hulls of a more cruiserly craft. And because cats have so much volume and deck space, it’s easy to load them up. An average 40-foot cruising cat with a hull-to-beam ratio of 8:1 has a pounds-per-inch- immersion measurement of about 1,300 pounds. One hundred gallons each of diesel (700 pounds) and water (800 pounds) will set it down an inch. A 50-pound anchor with 250 feet of 3/8-inch chain adds 450 pounds, and you’ll probably want three anchors, a couple of spare rope rodes, and half a dozen mooring warps, bringing you close to the second inch. Add a generator in its sound shield, an air-conditioning compressor, and a foursome of air handlers, plus a battery charger and an inverter, and you’re looking at your third inch. It’s not unusual on a 40-foot cat to see a 12-foot RIB with a 20-horsepower outboard, a rig that can easily weigh 500 pounds, slung from davits that weigh another 100 pounds. Add to that a barbecue, diving gear, a kayak, and a windsurfer, and you’re well on your way to your fourth inch. We haven’t yet added tools and spares, never mind food, beverages, pots and pans, linens, or even people. If you attain the advertised capacity payload, which for a 40-foot cat might be about three tons, the boat will float almost five inches below its designed “light ship” waterline.

When the boat floats lower, wetted surface grows. If the transoms immerse, drag increases significantly. Perhaps more important than the lost performance, the wingdeck clearance is also reduced. The closer the boat’s wingdeck is to the water, the lower the sea state in which it’s likely to interact forcibly with waves, a situation that’s again uncomfortable and slow.

The tendency of boats to accumulate weight hasn’t gone unnoticed by their builders. In several instances, a revised model has simply been lengthened. Two examples are the Dolphin 460, which started life as the Dolphin 430, and the Manta 42, which grew from the Manta 40. Both benefited from their sterns being stretched out. They gained volume aft, some of it below the waterline, supporting the added weight that seems to accumulate back there, around the engine compartments and in the aching voids under cockpit seats and coamings. Extending the existing hull lines farther aft raises the transoms, too, and as long as the bridgedeck remains unchanged, it’s now a little more centered on the longer hulls, and the new combination should be less prone to pitching.

Eyeball the transoms and the stems while the boat is afloat and look around the boat to determine its load condition: Are the fuel and water tanks full? Is there a generator? How many anchors and mooring lines? Are provisions and stores aboard? How many people?

If you want to make the most of the boat’s sailing potential, pay attention to how much gear you bring aboard. Take inventory regularly, and send ashore anything that hasn’t earned its place aboard. Keep those transoms clear of the water.

**

Loads and Righting Moments: A cat bears heavier loads because of its inherent stability**

If cruising catamarans have failed to live up to the mayhem predicted by early critics–oceans littered with upturned boats–it’s due in large part to lessons learned from accidents with early racing machines. Many capsizes were the result of the lee bow immersing under the dual influences of wind pressure and wave action, which caused the boat to pitchpole. A key factor proved to be the relationship between length and beam. It’s no coincidence that the maximum beam of a cruising cat rarely exceeds 55 percent of its length. And high freeboard forward isn’t there simply to provide headroom but to create reserve buoyancy in that all-important lee bow.

It’s rare for a catamaran to capsize under wind force alone. To render the chance as unlikely as possible, designers limit the sail area of vessels (such as charter boats) that might end up in the hands of less experienced cat sailors. A typical situation that might catch the unwary is a tropical rain squall, in which the wind can gust from 15 to 30 knots in seconds. Even with sail areas small enough to minimize such a threat, most cruising cats have adequate sail power–sail area-to-displacement ratios in the low 20s–for all but the lightest conditions.

The reason for employing such a cautious approach to design is simple: Catamarans don’t give the same clues as monohulls do when they’re overpressed. Most important, they don’t heel.

At small angles of heel, a monohull has a small righting moment. As wind strength increases, a monohull responds by heeling, which dampens the shock load in much the same way as a stretchy nylon line absorbs energy. A monohull’s righting moment increases until the heel angle reaches about 60 degrees, and it remains positive well past 90 degrees, at which point the heeling force becomes minimal, and the boat begins to right itself.

A cat’s righting moment is the resistance to immersion offered by the leeward hull. It starts out as a measurement much greater than a monohull’s, so the boat is unable to absorb wind gusts by heeling. A wind force on the sails that would cause an average 45-foot cruising monohull to heel 15 degrees would heel our average 40-foot cat only three degrees.

When a cat does heel, its righting moment increases until the leeward hull carries the entire weight of the boat and the windward hull is flying. For practical purposes, designers consider this the angle of vanishing stability because from this point on, as the boat heels farther, righting moment diminishes rapidly as the center of gravity moves closer to the leeward hull. On our theoretical average boat, this angle is about 16 degrees. It’s fairly general practice among naval architects to design cruising cats so that in theoretical static loading conditions, this point won’t be reached in winds under 35 knots.

As discussed in “More Righting Moment Means Less Heel” (see the sidebar), the maximum righting moment for an average 40-foot cat is approaching twice that of an average 45-foot monohull. Since this is the starting point for calculating rigging loads, it follows that spars and standing rigging have to be substantially more rugged. Here, the cat’s wide platform works in its favor: The wide shroud base reduces the shroud load needed to support the spar, which in turn reduces the compression loading on the spar. Nevertheless, working loads are high, and standing rigging tends to be heavier on a cat than on a monohull.

Moreover, the compression load from the mast must be carried in an unsupported area, literally in the center of a beam, and the headstay load likewise. These loads and the racking forces generated as the boat moves through a seaway demand structures meticulously engineered to be stiff. Any flexing will generate damaging cyclical loads in the hull and the rigging.

However placid a catamaran may appear at rest, once it gets moving, it’s a powerful creature and deserves respectful handling by the crew.

**

Sailing a Cat: Attention to trim and reaching sails can provide a large speed bonus**

To power the boats under sail, designers, with few exceptions, have settled on fractional rigs with small overlapping headsails and big, roachy, full-battened mainsails. This is a combination that’s easy to control and keeps the center of effort low, which is helpful in obtaining maximum sail area while limiting, if not eliminating, the potential for capsize.

Small headsails keep headstay loads low. This makes backstays less important, to the degree that they can be replaced by upper shrouds led well aft, where, well outboard thanks to the wide beam, they don’t interfere with the roachy mainsail.

But speed and performance aren’t givens. “Four things make catamarans slow,” says Gregor Tarjan of Aeroyacht. “Weight, of course. Then a dirty bottom, baggy sails, and an inattentive crew.” That sounds a lot like the operating condition of many cruising boats, but at least a cat crew that pays attention can work to ameliorate any other deficiencies.

While the first impression gained on stepping aboard a cat and into the opulence of a fruitwood-trimmed saloon is of unabashed ease and luxury, these boats demand physical activity when under sail. In-mast mainsail furling has no place here-such a sail simply doesn’t have the needed power or tunability.

Cat mainsails are big, and they’re heavily built to withstand high working loads. Setting and stowing them requires effort (or help from the winches). Bigger mains go up on two-part halyards, and cat builders often provide a winch on the mast. An electric winch, or a convenient lead to the anchor windlass, can be a great help. The sail is usually stowed in a boom-mounted sail bag, but the high house and (frequently) solid bimini roof make packing it a relatively easy task, as long as access to the roof is simple and secure.

Trimming and steering a catamaran call for a delicate touch. Its great beam means a cat can be fitted with a long traveler with which to minutely control the set of the main, the boat’s primary driving force. And because that force can be so powerful, midboom sheeting is unusual. Under way, the mainsheet is the safety valve, typically controlled on a winch mounted near the helm.

Changes in heel angle are so subtle that you have to focus on telltales and the speedo to measure the effect of sail adjustments. You’ll also likely want to tack downwind, because achievable reaching speeds, even in moderate airs, are so much faster than sailing on a dead run.

For light windward work or moderate-air reaching, a reaching sail (variously called a gennaker, screacher, or code zero) can add knots and excitement. Set flying on a furler or, in the case of an asymmetric spinnaker, from a sock, it’s easy to hoist and recover from the vast foredeck. Several builders offer bowsprits, and some support tacking the sail to the windward bow when off the breeze. On the Gemini 105Mc, an optional track spans the bows so the sail can be set to windward on either jibe without detaching the tack.

On any sailboat, the enjoyment you get from sailing is directly proportional to the effort you put into getting the best out of the boat. In the right conditions of steady breeze and flat sea and with an active crew, a catamaran can almost match a ride on a magic carpet.

**

Speed, Economy, Comfort: You can have any two of these**

Legendary multihull designer Dick Newick is generally credited with coining the speed/economy/comfort triangle as it applies to multihull sailboats, though it’s true for vehicles of any kind. Essentially, you can have any two of these qualities at the expense of the third. You can have speed at a low price if you’re willing to give up comfort, and you can have comfort at a low price if you’re willing to give up speed. If you want some of both, expect to pay for them.

If we take a couple of examples from the current multihull marketplace, we can see how effective the triangle is in measuring what you get for your buck. The Gunboat 48, which won the award for Most Dramatic Moment during CW’s 2006 Boat of the Year trials (see “Liftoff,” Editor’s Log, December 2005), has a light-ship SA/D of 32.3, making it far and away the most powerful of the catamarans reviewed. Another way to look at power in a cat is to compare displacement to the boat’s footprint, or length times beam. The Gunboat weighs a shade under 17 pounds per square foot, while three others in the Boat of the Year competition–the Lagoon 500, St. Francis 50, and Jaguar 36–came in between 25 and 27.

So what does it cost? The Gunboat is fully tricked out for cruising with beds, heads, galley, and the works, but everything is pared down to save weight, and the package comes in at a cool $73.45 per pound of displacement. The Lagoon 500 costs $17.35 per pound, but fashioned more for comfort and loaded with amenities, it weighs 131 percent more. When sailed in top-performance mode, the Gunboat behaves like a racing boat, demanding constant close attention from the crew. The Lagoon, while capable of a fair turn of speed off the wind, won’t keep anyone’s adrenaline gland on a hair trigger, but most will find it both slower and more relaxing to sail.

These boats also represent two other extremes in the market. The Gunboat is essentially custom built of advanced, lightweight, and high-strength materials. The Lagoon is built largely of standard materials in great numbers on a sophisticated production line by a company (Groupe Bénéteau) with enormous purchasing leverage.

The cost-per-pound measure is a useful starting point for someone looking to get the most stuff for the dollar, but as the above example shows, it needs to be weighted with other factors, such as where the boat is built, by whom, with what materials, and at what level of outfit.

High-volume builders, led by Lagoon and Fountaine Pajot, produce large numbers of boats in a wide range of sizes to a recognized standard of construction. Options are limited by the economics of the production line, but you usually have a choice between layouts for “charter” or “owner” use. Yards that build fewer boats per year, such as Privilège, offer a broader range of options, and as a rule you can expect to pay more in proportion to the degree of customization you seek. Switch Catamarans builds only four boats a year, each one highly customized around the essential structural components. Manta, one of three U.S. catamaran builders, builds about 10 Manta 42s a year, each to order. It offers a choice of finish materials, and it controls the cost of personalizing the boats by grouping extras in incremental packages.

The largest producers don’t build much under 38 feet, although Fountaine Pajot is introducing its Mahé 36 this year. Numerous smaller builders take up the slack. The Maine Cat 30 and Performance Cruising’s 33-foot Gemini 105Mc illustrate two ways of addressing the problem of fitting livable quarters into shapes that please the eye. Below 30 feet, on smaller hulls, you’re moving into day-cat territory.

If you’re looking to defray some of the cost of ownership and sub out the maintenance to someone else, there’s always the charter business, which has absorbed a large portion of worldwide catamaran output. The Moorings sells its own branded version of Robertson and Caine’s Leopard line, and many boats built by Voyage Catamarans enter that company’s integrated charter business. Most bareboat companies large and small have cats in their fleets, so you can board your cat close to home or, if you prefer, in a favorite cruising ground.

First, you have to decide what you want your buck to buy: frills or thrills? Maybe you should take a test drive first.

**

Cruise Before You Choose: Whether on charter, as a demo, or with a friend, take a test sail**

Purchasing a catamaran for the first time represents a big investment, not just in money but in a different style of onboard living and boathandling. Happily, you don’t have to jump in without testing the waters first. There are many ways to get hands-on experience of cats and the cat experience before making the leap.

Every October, the U.S. Sailboat Show in Annapolis, Maryland, is a great place to view a variety of cats, and Performance Cruising hosts Multihull Demo Days (www.multihulldemodays.com) for several builders shortly thereafter. Many of the companies that have been exhibiting at the show make boats available for brief demonstration sails, so this is a good chance to check out several boats in a condensed period of time. The Miami Strictly Sail show in February also has dozens of cats to view dockside.

But at any time of year, one of the best investments in trial sailing is to take the entire family for an extended introduction to what their new onboard roles might be by chartering a cat. You’ll learn a lot by moving aboard any boat for a week. And to get a jump on the special handling techniques involved and to flatten your learning curve generally, you can also hire and take along an experienced skipper. You can even go whole hog and charter a fully crewed cat, learning from professionals while being pampered.

Charter opportunities abound. At one end of the supply spectrum, the fully integrated Catamaran Company () provides every service, from selling new boats to bareboat and crewed charters worldwide to brokerage sales of used boats. Major charter companies, including The Moorings (), Sunsail Sailing Vacations (www.sunsail.com), and TMM Yacht Charters (www.sailtmm.com), feature catamarans in numerous locations. Even smaller builders often have unique trial opportunities. For example, Maine Cat (www.mecat.com) operates a single base in the Bahamas where you can charter a Maine Cat 30 or 41.

If you enjoy traveling in company, Cruising World Adventure Charters hosts a Sail-a-Cat flotilla (www.sailingcharters.com) every year in the British Virgin Islands. This is an opportunity to share impressions with like-minded sailors-not to mention that on this year’s trip, you’ll get a chance to spend time with Cap’n Fatty and Carolyn Goodlander.

For a more ambitious immersion in catamaran sailing, you could hook up with a crew-networking outfit, such as Offshore Passage Opportunities (), through which you might find a crew position on a delivery.

The chances to learn about cat sailing don’t end with a purchase, however. PDQ Yachts runs a program called PDQ U every summer on Lake Ontario for owners taking delivery of their new boats.

Jeremy McGeary is a CW contributing editor.