Do you ever have a feeling that your life is about to change?” My wife said these words to me as we parked our Toyota 4Runner in front of the covered warehouse containing a 31-foot Hallberg-Rassy Monsun from 1975. I didn’t know what struck Missy, but I shrugged it off. “Let’s leave our emotions here in the car,” I said. I was lying. For the previous two months, I had been admiring this boat online, asking the broker for more pictures, and digesting anything that had information about the Monsun. Even before seeing the boat in person, I had dreams of following along the tracks that John Neal wrote about having sailed in his Monsun, which he owned for 11 years and sailed 44,000 miles before selling it in Australia. We wanted our first keelboat to sail (with Poseidon’s blessing) from our home port on Lake Erie to the Pacific.

At that moment, though, I had to reel back my mind to where I was standing in Michigan. I had learned from reading all the books that you have to leave your emotions out of buying a sailboat. Which, in all honesty, I think is a bunch of baloney. Why shouldn’t you fall in love with something as time-consuming, money-depleting and frustrating as an old sailboat?

Anyway, it was time to focus. I had to find a reason not to buy this boat.

The broker unlocked the warehouse and turned on the dim, fluorescent lights. The warehouse could fit about 50 average-size sailboats, but only about 10 were left on the hard that season, all tucked back into the corner. After five minutes of searching, we found the boat.

The hull looked and felt solid, fair and clean. At first glance, the gelcoat looked outstanding for a 45-year-old boat, and even the nonslip on deck was still in good condition. The downside was that when we went inside the cabin, there was a strong odor coming from the head and holding tank. The cushions no longer had any resilience, and the covers needed replacing. Missy and I were too infatuated with the cockpit to care. It was covered in teak, and it felt snug and secure. The interior mahogany seemed so nautical.

And then I opened the engine bay to see the Yanmar 3YM30, outfitted to the boat in 2015 and with only 200 hours logged. The engine looked immaculate, something I wouldn’t mind working on.

A clean engine bay was a major checkpoint for me. It meant that the previous owner had cared. Not only that, but when something broke, I would be able to hop in and fix it without later stepping into our boat’s cabin covered in grease.

The sails still had their inspection tags from the sailmaker for their yearly service. And, being a freshwater boat, it had rigging in decent condition.

That was it. The boat had its flaws, but we were sold.

Making the monsun shipshape

We closed on the boat after the survey and arranged to have it shipped to our marina in Monroe, Michigan. Our project list was built on our bluewater passagemaking dreams, which we’d spun up by reading Don Casey’s This Old Boat and Inspecting the Aging Sailboat, listening to Andy Shell and crew’s 59° North (now called On the Wind) podcasts, clicking around John Harris’ website, morganscloud.com, and scouring our surveyor’s report. Everything we wanted to do would be in our spare time because we were working full time. On the weekends, we would haul our tools to the marina and work on the boat throughout winter. Our goal was to fix up the boat in two years, and then cast off the lines.

We followed the basic principles that Schell and Harris preach: Keep the water out, keep the rig up, and keep the crew happy and healthy. We added a fourth item: Keep it small and simple.

Keeping the water out required us to replace all the original through-hulls, which had gate valves as seacocks instead of ball valves. We also had to replace the hoses and clamps for the deck scuppers and cockpit drains.

We went with Groco IBVF seacocks and flanged adapters, and Scandvik ABA hose clamps. Replacing the through-hulls was an intimidating project, but the most technical aspect was ensuring that the through-hull and flange were flush to the hull inside and outside. It took some time to level the inside of the hull with epoxy resin and colloidal silica filler. With lots of sanding on the inside of the hull, and patience, we were able to ensure a watertight seal once the 3M Marine Adhesive Sealant 5200 was applied.

During the survey, we had noticed some evidence of water entering from the lower shroud plates, so another task was to remove the U-bolt-style lower shroud plates. Then we had to remove any of the core that seemed to have water intrusion. We filled it with epoxy and redrilled the original bolt holes. I went to a local machine shop and had them fabricate the backing plates out of quarter-inch 316 stainless steel.

That mom-and-pop shop with a couple of CNC machines was able to knock out the job in no time. As a plus, they became enthusiastic followers of our journey.

Five frustrating inches

Next we focused on keeping up the rig. The rigging was old, its age unknown. So, even though the boat was lightly used for four months out of the year and had never seen salt water, we still decided to replace the rigging. The turnbuckles were replaced the first season with BSI turnbuckles and toggles. The following season, we replaced the 1-by-19 wire, ordering the length of wire and mechanical Sta-Lok terminals online from Defender. We took the measurements of the stays in January, but we didn’t get around to cutting them until much later. We cut the backstay in May, a few days before the boat was ready to splash.

When we stepped the mast, Missy informed me that the backstay wasn’t going to reach the chainplate. “Well, unscrew the turnbuckle. It will fit,” I said.

She replied with, “It’s about 5 inches short, and the turnbuckle is on its last few threads.”

My heart sank. We were going to have to take off the mast and wait for another order of wire to replace it. But in a pinch, we found a Dyneema strop and a soft shackle that we could use as an extender. That combination allowed us to step the mast and move the boat over to our dock slip.

We left the rig only hand-tight and did not bend on the sails. Once the new order of 1-by-19 wire showed up, I began cutting again, checking and double-checking measurements. In front of our boat slip, I used a mini hacksaw and a homemade miter box to make a clean, perpendicular cut.

Once the backstay was cut and ready to go, Missy went up the mast, after setting the halyard and topping lift as additional temporary backstays. To my disbelief, once again, the backstay was short.

“What the heck!” I yelled in frustration.

“How is this so off?” Missy asked with undertones of blame.

Both times, I had cut the backstay 5 inches short. I finally figured out that I was failing to account for the difference in swage and Sta-Lok length (about 2½ inches on each end). I learned that, when measuring stays, it is important to make a simple sketch or note stating exactly where the measurement started and ended, even if you are freezing your butt off while taking the measurements in Michigan in January.

The third time, Missy came up with a plan to ensure that the length would be correct. I would first attach the Sta-Lok fitting to only one end, and Missy would go aloft and connect the fitting to the masthead. Then I would cut the backstay to the correct length by visually checking it.

Finally, we had a backstay. With this setback, the rest of the rigging waited until we were on our way along the Erie Canal. The remaining shrouds were cut with the mast down, on the free dock in Waterford, New York.

Getting comfortable

The most daunting and time-consuming of the tasks was keeping the crew happy and healthy. To us, this meant staying well-rested and well-fed, and living in a clean environment. Our boat had been a Great Lakes vacation cruiser. Used lightly and only for the summer season, it wasn’t outfitted for full-time living aboard.

Since we would spend every day sitting and sleeping on the boat, we decided to replace the cushions and covers. We transformed one bedroom of our two-bedroom apartment into our canvas loft, and another room into boat-parts storage. This meant that our bed would have to be relocated to the living room, which we figured would be good practice for living in a small space. Missy measured all the cushions, including the V-berth, and came up with a quantity of foam, Sunbrella, underlining fabric and zipper length. Before ordering, we tried Sailrite’s foam sample box to find the perfect foam firmness. We placed the 6-by-6-inch foam samples on the ground, testing each to see what worked best for us—which would have been a funny sight to see, trying to test a cushion with our butts halfway on and halfway off the tiny samples.

Missy then cut out the cushions using an electric knife, the kind regularly brought out for Thanksgiving turkey. All of the cushions required curved edges along the hull, which required Missy to make two measurement lines (top and bottom), and then cut the cushions at an angle. To make this complicated cut, I would sit under the cushion and guide one side of the blade to make sure it was still on the cut line. The cushion edges were not perfect, but, by oversizing the cushion slightly and using Sailrite’s plastic-shrink method, the small imperfections were no longer noticeable.

The cushion covers were sized and sewn to the same dimensions as the original Hallberg-Rassy. This resulted in a skintight fitting. Missy decided to modify the settee cushions, changing them from a single 6-foot-long cushion to separate cushions that matched the stowage underneath. This greatly improved our access to cans of beans and tuna below the settees. Missy also cut the fabric-wrapped backrests in half so that we wouldn’t have to clear off an entire side of the salon to access underneath.

I had learned from reading all the books that you have to leave your emotions out of buying a sailboat. Which, in all honesty, I think is a bunch of baloney. Why shouldn’t you fall in love with something as time-consuming, money-depleting and frustrating as an old sailboat?

And finally, to keep us snuggly in our bunks underway, Missy sewed some lee cloths out of Phifertex and binding, with pockets for quick storage of a headlamp, headphones, a book or a cellphone. She used webbing and buckles to allow for quick tensioning, and ease of ingress and egress. Every time I come in to rest on our boat, I still marvel at how amazing the cushions look and feel.

Getting even more comfortable

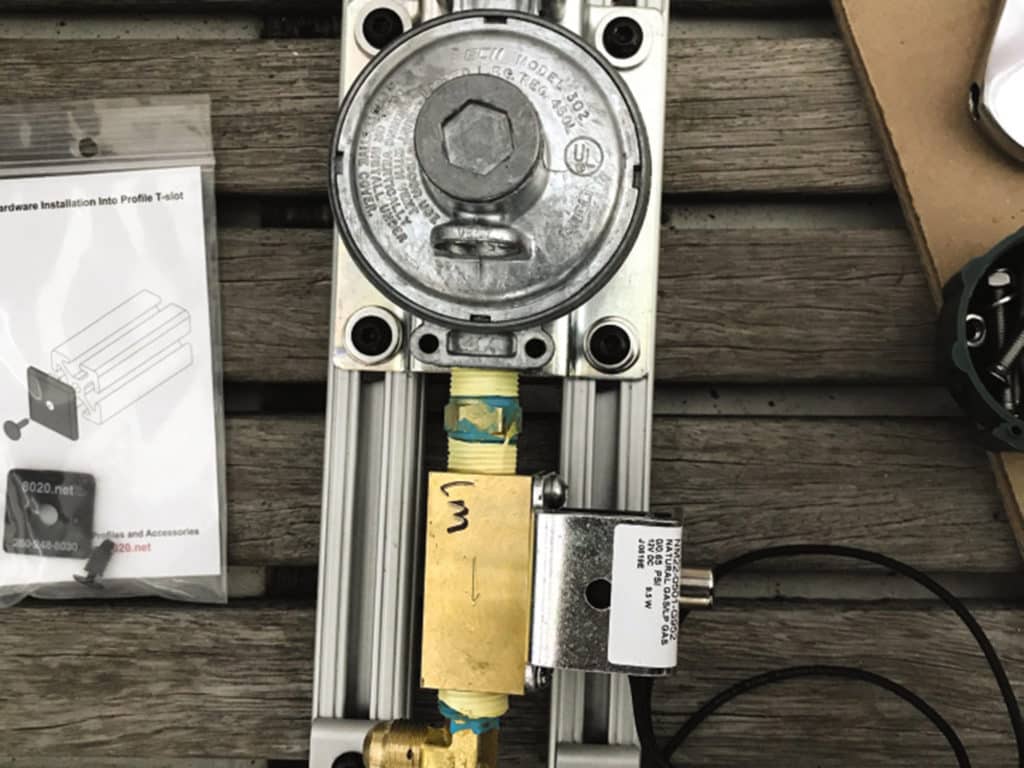

When we first received our boat, it came with an Origo two-burner stove. We kept the alcohol stovetop for the first summer, but it became obvious within the first two weekends that it was not for us. I immediately grew tired of refilling the alcohol, which always seemed to be empty in the morning when we wanted to make coffee. The following winter, I replaced the Origo with a Force 10 two-burner propane stove and oven. It’s a major luxury to be able to light the stovetop without a lighter or match, and without fumbling around the cockpit locker to find the denatured alcohol.

Then there is the added benefit of oven-baked fresh bread, which my wife said was a requirement for our new lifestyle. Since beginning cruising, she has made bread on the Hudson River approaching New York City, while underway in the Atlantic bound for Marsh Harbour in the Bahamas, and many times throughout the islands.

We also tried to go down the path of no refrigeration. We did it as part-time liveaboards the first summer. We bought bags of ice every weekend. Then we attempted it as full-time liveaboards. But halfway through the Erie Canal, we ordered an Engel fridge and had it shipped to meet us in Annapolis, Maryland. For vegetables and eggs, we chose to keep our icebox filled, which meant that every two or three days, we were buying a bag of ice. If I wanted cold beer, I had to splurge for two bags of ice.

Man, was the fridge worth it. Enjoying a cold beer off Hawksbill Cay in the Exumas while sitting waist-deep in crystal-clear water on a mile-long sandbar with new friends was bliss. The only downsides of the fridge are the space it takes up and the extra 100-watt solar panel we had to add for the energy use.

Setting off aboard Ukiyo

With these changes and many other small projects done, we planned to set off from Monroe, Michigan. We quit our jobs, terminated our apartment lease, and attempted to move onto the boat. We struggled to fit all of our stuff aboard, so we laid out everything on the lawn in front of our slip. Curious dock neighbors came by later that evening, worried we were dividing up our belongings and separating.

After two more weeks at the dock, we were bound for Annapolis via the Erie Canal, Hudson River, New Jersey coast and Delaware Bay. In Annapolis, we spent five weeks on a second refit geared toward offshore sailing. We anchored the boat up the Severn River near Severna Park, Maryland—my childhood hometown.

With the help of my family, we had a mooring ball and access to a dock. My dad and I worked for weeks to finish some major items. We installed a Hydrovane self-steering system, replaced our 50 feet of three-eighths G4 chain with 125 feet, swapped out the 35-pound CQR anchor for a 44-pound Spade anchor, and added deck fittings and reinforcements for the Dyneema removable inner forestay. We also bought new sails and completed many minor projects. It was a real treat working with my dad, and my mom always had a world-class dinner ready when we got home.

All of these items, in my mind, fell under the category of “keep the crew happy and healthy.” You see, happiness to me is sleeping soundly and staying well-rested at anchor and underway. Adding a Hydrovane, which acts as our third crewmember and steers the boat perfectly offshore, allowed Missy and me to relax. And the oversize Spade anchor has been worth every penny during winter cold fronts that blow through the Bahamas.

Meanwhile, Missy converted my parents’ basement into another canvas loft. This time, she spent two weeks redoing our dodger and dodger frame. The smile on her face when the test fit was successful rivaled our wedding day.

Finally, we added critical safety equipment, including an ISO-certified life raft, an EPIRB, two personal locator beacons and a new manual bilge pump. Then we were off to Morehead City, North Carolina, to wait for a weather window for a five-day trip offshore to Marsh Harbour.

All in all, with our refitted boat, we spent three months cruising across Lake Erie and along the US East Coast, and then four months cruising the Bahamas. We waited out hurricane season in Luperón, Dominican Republic, with plans of sailing the Eastern Caribbean before heading west to Panama.

The refit almost broke us a few times, even before we left the dock. There were so many unknowns, from how we would shower to whether we could actually live in such a small space. Once we left the dock, though, we immediately adapted to our new home and lifestyle.

As we continue our journey, we wake up every morning not knowing what the day will bring. Will we swim with eagle rays? Run aground? Lose our dinghy? Adopt a kitten?

We never know. To us, this is what life is all about. It’s all part of the adventure.

Follow Missy Hearn and Greg Thomasson’s journey on Instagram @sv_ukiyo or on their website, thirdreefadventures.com.