January 2017 found me in Durban, South Africa — off which runs one of the world’s great ocean currents, the Agulhas — preparing Gannet, my Moore 24, for an ocean passage and not seeing the weather I wanted. Eventually, I left anyway, and rode out two gales at sea.

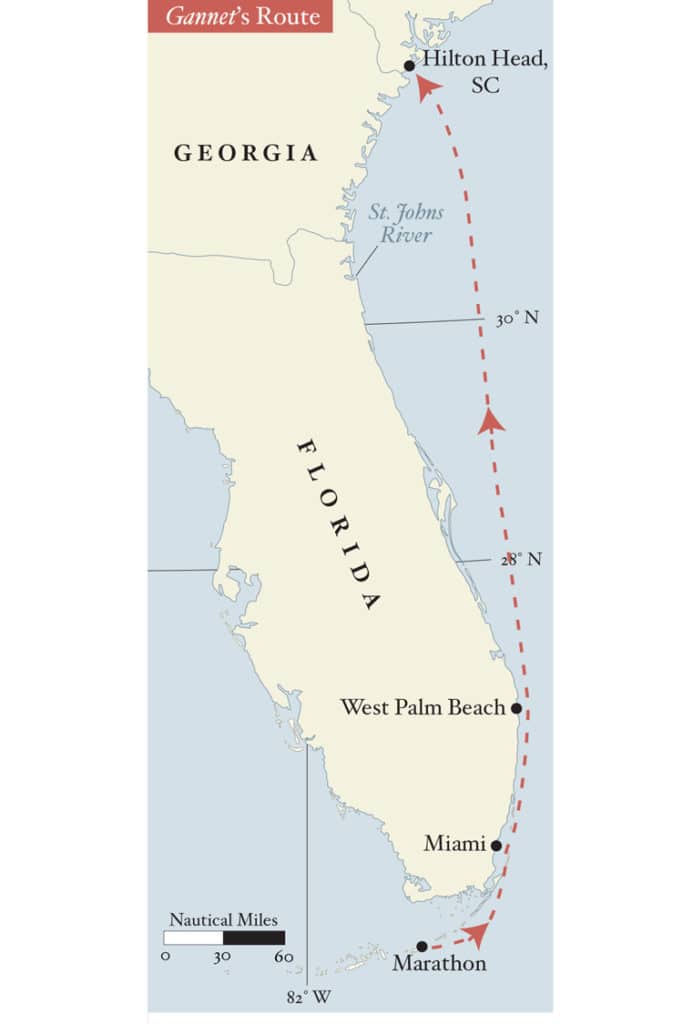

January 2018 found me in Marathon, Florida, where Gannet survived the previous fall’s Hurricane Irma undamaged on the hard at Marathon Boat Yard and off which runs another of the world’s great ocean currents, the Gulf Stream. Again I was preparing the little gray sloop for an ocean passage, this time north to South Carolina’s Hilton Head Island, where my wife, Carol, and I had just bought a condominium overlooking Skull Creek Marina. Again I was not seeing the weather I wanted, and again I left anyway.

Before I go to sea, I check weather with several iPhone apps — Windfinder Pro, Windy, MeteoEarth — and I download GRIBs on my laptop with LuckGrib. Once I go to sea, I check the barometer and study the waves and sky and live with whatever happens. At least thus far.

In Marathon, I wanted wind from the west or south. What I got was a week of strong wind from the north. When that finally ended, the forecast was for wind from the east for two days, veering southeast, then variable to dying as another front approached, followed by two days of 20-plus-knot northerlies gusting to gale strength.

The east wind would mean beating the first 60 miles along the Keys, but it would then be a reach when I could make the turn north. I didn’t know how far I could get before the front reached us. There are harbors on Florida’s east coast in which I could find refuge. I studied the charts and considered some, but knowing that once I go to sea I tend to remain there, I expected I would head offshore to gain sea room and heave to or lie ahull and ride it out. So on Saturday morning, January 19, I left.

I had mounted the electric Torqeedo outboard onto its bracket several days earlier. I had started and put it into gear each day. I had tested it that morning. I pushed Gannet away from the boatyard wall, reached back and turned the throttle handle, and got nothing except a display reading, “Error 32.”

One of the often-overlooked virtues of jib furling gear is that you can quickly get under sail when your bleeping motor dies. I unfurled the jib. Fortunately, the light wind was from the northeast, and I could ghost out the narrow boatyard channel cut through mangroves on a reach and then turn west on a run down the channel to the ocean.

After clearing a now always-open bridge, I had a little space and set the tiller pilot to steer while I disconnected and reconnected the Torqeedo’s tiller arm. The engine whimsically decided to run, and I continued down the channel at 3 knots under jib and Torqeedo. The Torqeedo was useful when, at several places, the wind was blocked by buildings.

Past the last of the channel markers, I turned south and raised the main. About this time the Torqeedo died again, but it did not matter. I got us under full sail and removed and stowed the offending motor, outboard bracket, fenders and dock lines.

East wind was forecast, and I had planned to sail south to Sombrero Light and the deep water beyond the reef before tacking. However, the wind remained north-northeast, and we sailed closehauled on port tack at 5 knots inside the reef, up what is called Hawk Channel, on a course that would take us into deep water in 10 or 15 miles. This was just as well because the depth finder was not working. It consistently displayed depths of 2 and 2.1 feet. When against the boatyard wall, I thought this was approximately accurate. Obviously, it wasn’t when we were in 20 to 30 feet of water. This too wouldn’t matter once we passed into the Florida Straits and into thousands of feet of water, until the last few miles into Skull Creek, where I would have to pay close attention to our position on the iNavX or iSailor apps.

The sun never quite burned through the overcast, and in early afternoon the wind veered to the east, forcing us off to the southeast, and increased to 18 to 20 knots, causing Gannet to heel more than 30 degrees. Life on Gannet heeled more than 20 degrees is harsh.

I don’t think of Yogi Berra, a great athlete and an American original, often enough, but in January 2018, I did. It was, as Yogi famously put it, “déjà vu all over again.”

I was sailing with brand-new laminated North 3Di sails. Impressively constructed, they’re beautifully shaped, with an unfamiliar hard plastic finish, and almost unbendable. Once out of their sail bags, they were never going in again. I partially furled the jib and put a reef in the mainsail. As often happens, the ride smoothed out and our speed increased, though we were still occasionally thudding off waves.

The jib has foam along the luff to help it maintain better shape while partially furled. This is common, but I have never before had such foam. I noticed when furling the sail at the dock that it makes starting the initial wrap difficult. That afternoon, with wind in the sail, it made it impossible until I led the reefing line to a winch. I’ve used winches to reef jibs on other boats. This was the first time on Gannet. That might be a measure of the power in the 3Di sails.

The reefed sails maintained good shape. The first reef on the main is deep, around the normal second reef level, just as I want. And the second reef is near storm trysail level. Gannet doesn’t need much sail area to keep moving.

The night was painful. At 1800, a mile off Alligator Reef, I came about and headed east-southeast into deeper water. If the wind remained steady, I thought that if I tacked again at midnight, I would clear Elbow Reef and be able to turn north.

The wind did hold steady, but it increased in strength, gusting in the low 20s, heeling Gannet more than I wished and causing her to bash into and leap off waves. No matter how many cushions I used, I was unable to find a comfortable position behind the lee cloth on the port pipe berth. I suppose I dozed from time to time, but I was up often, looking for ships, and seemed always to be awake.

At 2300, a cruise ship was a mile north of us, with the loom of the lights of two other ships to the south. I decided to tack away from the traffic and came about onto starboard.

Even though I furled the jib down to a third of its size, our speed over ground jumped from 5 knots to 7 and 8. Obviously, we were in the Gulf Stream and now moving with it rather than across it.

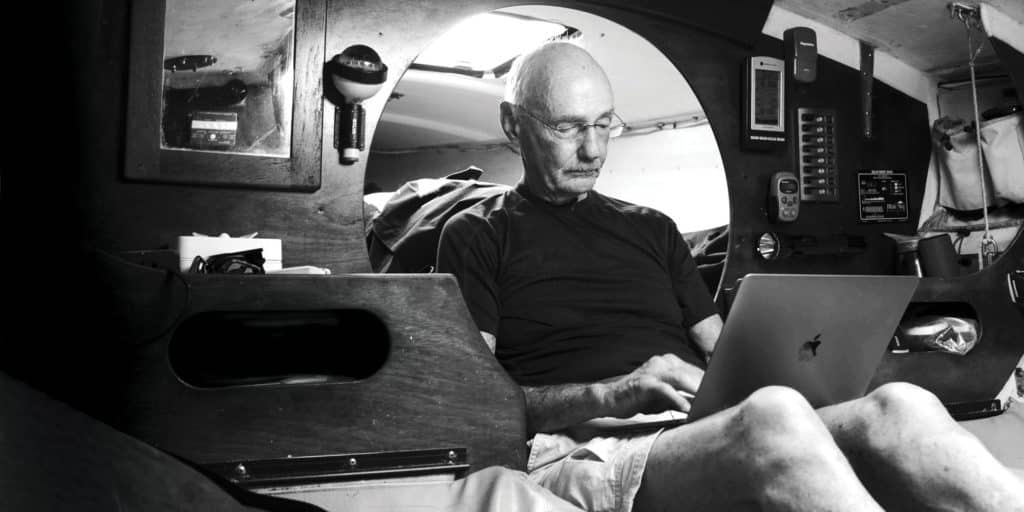

I didn’t see any more ships. I don’t know that I got any more sleep. At 0400 I got up, as I would each morning of this passage, and wedged myself into the position I call “Central” sitting in a Sport-a-Seat on the floorboards, facing aft, where I managed to doze intermittently until first light, when I went on deck and furled the jib down to storm-jib size.

The wind finally veered enough so that we cleared the last reefs, and as the morning progressed, I was even able to ease sheets. What had been an ordeal became fast sailing, with current-aided speed over ground frequently in the double digits.

At 0730 I saw the Miami skyline through haze 8 miles to the west, but surprisingly had the ocean to myself. No pleasure craft. No ships.

As the wind continued to veer and diminished to 14 to 16 knots, I unfurled the jib and thought about unreefing the main, but we were going fast enough, and I was tired.

The second night was in complete contrast to the first: smooth, quiet, almost level and fast. I went to sleep at sunset. Got up often. Once saw the loom of lights of a ship to the east. And Gannet continued to roar up the coast.

At 0900 Monday we were off Cape Canaveral. At noon, Gannet concluded her best day’s run ever of 185 miles. My experience is that the fastest sailing is the easiest, and the hardest the least productive. The waypoint off Hilton Head Island was only 168 nautical miles away, and I began to hope I could beat the front.

That afternoon was beautiful. Perfect. Warm. Sunny. I moved the Sport-a-Seat on deck and sat there, reveling in Gannet‘s speed and grace, sunlight on waves. A single fat flying fish took flight. I brought the Megaboom speakers up and listened to music. The universe is beyond imagination. Time is long, and you are here only for a butterfly’s cough. Cherish any moment you can. I did.

At sunset, the waypoint off Hilton Head Island was 130 nautical miles away. A 6-knot average would see us in our slip at Skull Creek Marina before dark Tuesday. iNavX and iSailor showed our ETA at the offshore buoy around noon. My hope of outrunning the wind shift grew. I would rather not suffer. We would see.

I stood in the companionway in the early evening. Gannet was getting it done, making 8 and 9 knots. The sound of rushing water in darkness. First quarter moon silver on the water. The mouth of the St. Johns River 60 miles west of us. We were alone. Millions of people on the shore, and we had seen no one since the Florida Keys.

I was up again at 0400. These early awakenings were not planned, they just happened. This time, after jibing around midnight, I remained on the starboard pipe berth although it was now to leeward. I got up when a gust heeled Gannet enough so that the food bags on the other berth fell on me. The Hilton Head sea buoy was 52 miles ahead, and we were no longer in the Gulf Stream. Gannet‘s 6.5-knot speed over ground was all due to sails.

The wind had continued to veer and was now west and on our beam. Water was coming on board, but in part because of the small spray hood I had installed in Durban, not much was making its way below. I put on my foul-weather gear and sat at Central, drinking grapefruit juice, waiting for dawn.

With the sun came stronger wind, and Gannet began surfing at 10-plus knots. That rush cannot be overstated. I have never had a boat that accelerates as does Gannet. She is doing 6 or 7 knots, then a gust of wind or a wave, even slight, and suddenly she is doing 10 or 12 knots or more.

At 1100, the sea buoy was 12 miles ahead, and we were in thick fog. I dug out and pumped up the fog horn. Without a functioning depth finder, had I not had GPS positions in my iPhone chart-plotting apps, I would have hove to.

I crawled over the supplies stowed on the V-berth and dragged the anchor and rode bag back under the forward hatch. Even this far out, the water was shallow enough to anchor, but it would be rough. I never dreamed we would make it to Hilton Head Island in three days. The sky seemed a little lighter overhead. I hoped the sun would burn off the fog.

We passed within a hundred yards of the sea buoy. I heard it, but never saw it. Finally, as we approached the first set of buoys at the entrance to the channel leading into Port Royal Sound, the fog began to lift and I saw them.

Within an hour, the sky was clear and I could see the entire 10-mile-long ocean shore of Hilton Head Island. Although there were no other boats or ships around, I kept Gannet just outside the port line of buoys marking the channel. When we reached the mouth of Port Royal Sound in late afternoon, both wind and tide were against us.

I already knew that I wasn’t going to reach Skull Creek Marina before dark. We sailed and sailed, and tacked and tacked, trying to get deeper into the sound, without much success. Just before sunset I furled the jib and anchored in about 40 feet of water. We had come almost 500 miles, but still had 7 miles to go. I poured myself a drink and sat on deck, watching lights come on ashore. We were far enough in to be protected. The water was smooth.

The night was peaceful, if a bit cool at 38 degrees. A friend gave me a good sleeping bag in which I was comfortable, though it was hard to force myself out of it the next morning. After a cup of coffee, I dragged the Torqeedo onto the deck, mounted it on the transom and, behold, it started. The 7 miles to the marina would be near the limits of its range, so I turned it off, raised sails and anchor, and we beat our way up the sound against a light land breeze, but now with the tide with us.

Two hundred yards off the mouth of Skull Creek, I started the Torqeedo again and lowered the sails.

Coming into Skull Creek for the first time was beautiful. A sunny sky. Wind light. A flock of birds standing almost within arm’s reach on a sand spit off the Pinckney Island Nature Reserve to the north. A dolphin broke the surface and swam beside Gannet. A pelican glided past.

I had telephoned the marina that I would be coming in that morning. They were on the lookout for me, and as I slowly approached, Fred, the dock master, called that he would walk down to help with my lines. He did, standing first on the end of the dock, then going to my slip. I glided in and tied up at 1030 and thanked him.

We had easily outraced the front.

I looked ashore at our condo behind oak trees and Spanish moss. Gannet was home. She has never really had a home port. Now she does.

Webb Chiles will sail from Hilton Head, South Carolina, in January 2019 for Panama and then San Diego, California, where he will complete his sixth circumnavigation.