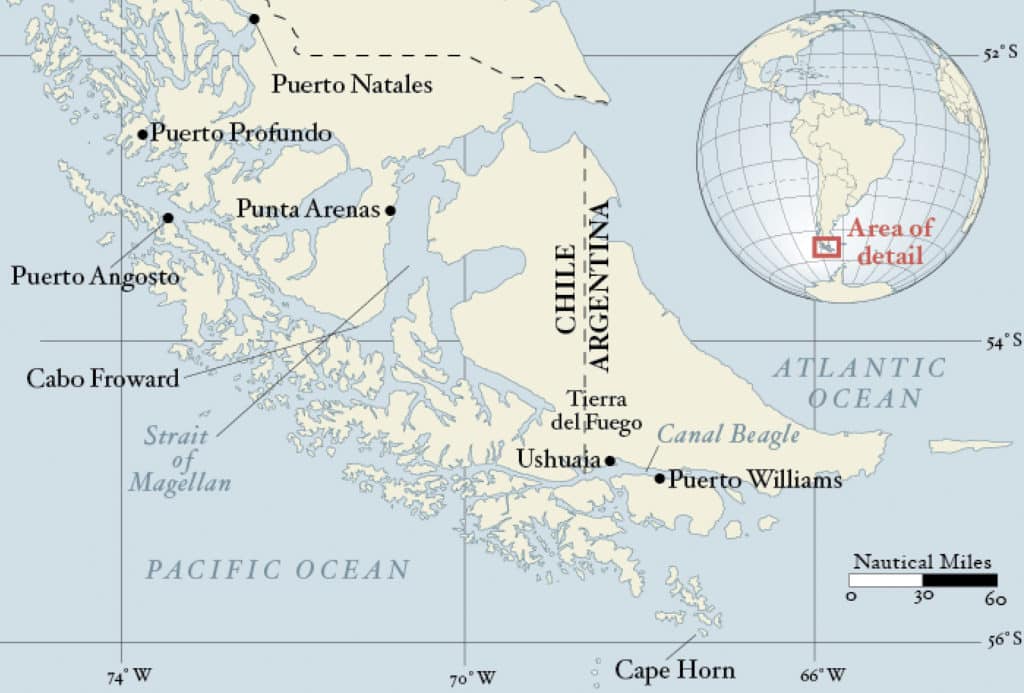

My wife, Alisa, and I were determined not to make bad weather the focus of our trip to Patagonia. But there was one night when the conditions lived up to their reputation. Galactic, our 45-foot steel cutter, was swinging at anchor in Puerto Natales, halfway down the 900 miles of fjords that make up Chilean Patagonia. Puerto Natales is on the inland side of the Andes, where we found the dry grasslands of pampas instead of the dripping rainforest of the coast. Sailing around Natales was just like sailing around Colorado — if Colorado had salt water, flamingos, and more dramatic mountains and glaciers.

But Puerto Natales has no well-protected anchorage. The famous Patagonia & Tierra del Fuego Nautical Guide, more commonly called the “Italian guide,” which is the definitive reference for sailing Patagonia, calls the anchoring situation there “just a step short of tragic.” And being inland of the Andes means that Natales is also subject to winds that come screaming down mountain slopes to surprise visiting sailors.

We had just put our boys, Elias and Eric, to bed. Without warning, winds began funneling over the Andes and into the open anchorage. A routine night on the hook suddenly turned into something beyond our experience in eight years of full-time sailing.

We rushed to get our dinghy on deck and deflated as the winds began to howl in the rig. And then conditions became completely unreasonable. Galactic was knocked from side to side in the dark night, taking punches of wind so violent that Alisa wondered whether the mast would touch the water. We were caught out with only 4-to-1 scope as the water started foaming and spraying around us, and our trusty 88-pound Rocna dragged a tenth of a mile before we got another anchor in the water. And we were the lucky ones. The 70-foot commercial boat anchored next to us was blown out of the anchorage completely.

This is the kind of story that comes to mind when you think of Patagonia, right? Paint-peeling winds, driving rain, pitiless conditions?

What if I mentioned that this happened in mid-June, just as the southern winter was locking down, and that we were about to head farther south in the very heart of winter, down into the far reaches of Tierra del Fuego. Our conditions would be cataclysmic, right?

Well, no. First of all, winter in Patagonia is a not-so-secret golden season, when the polar high extends over the southern tip of South America, bringing long spells of settled conditions.

But Patagonia also suffers from a reputation problem. The need to tell a good story has created an outsize picture of the challenges involved. Alisa and I read a lot of tales about sailing Patagonia before we arrived, and too many of them read as accounts by self-styled “expert sailors” who wanted us to know they were dealing with “extreme conditions.” Their stories began to seem like endless repetitions of “Patagonia: It’s really windy!” Surely, we thought, there must be more to it than that.

Luckily, we were right. Occasionally rotten weather is a part of Patagonia, sure, but it isn’t the essence of the place. That essence has more to do with qualities such as stillness, majesty and solitude. Experiencing these aspects of Patagonia from the deck of your own boat is still one of the great adventures to be had on the planet. And by doing the trip in the winter, we doubled down on that adventure. Going in winter gave us solitude in anchorage after anchorage. We went months without meeting another cruising boat. And winter turned a place that is persistently gray in the summer into a crystalline wonderland of blue skies and frosty white mountains.

The wind raged for three hours that night in Natales, and then was suddenly gone. Alisa and I were both a little dazed by the experience, and impressed at how our two boys, who have spent their entire lives at sea, could sleep through the nautical uproar. Completely unwilling to trust the weather at that point, we stood anchor watches until drowsiness and dull calm convinced us it was OK to sleep.

The next day, the harbor was mirror-calm. But when I went to the Armada de Chile, the Chilean navy, to request a zarpe, the paperwork that would give us permission to continue southward,

I learned that the port was still closed and no departures were allowed. Bureaucracy hadn’t caught up with the change in conditions. I was told the port would be closed a day or two more. And no, I couldn’t have a zarpe until it was open.

In Patagonia the weather might not be that bad, but the bureaucracy can require your most determined go-with-the-flow attitude.

Eventually, the armada officer agreed to give me a zarpe on the off chance that the port might be open the next day. This made me as pleased with my improving Spanish as it did at getting a little concession from officialdom.

When we left Natales, the whole crew was gripped with the excitement of heading farther south. We already had enough snow to let the boys make snowmen on deck, and that first taste of real winter made us eager for more.

Leaving Natales, we transited the narrows of Angostura White, where the tidal currents can run 10 knots. The excellent current tables produced by the armada saw us through safely, and Galactic was soon tied into Caleta Mousse, a perfect little cove, or caleta, tucked into the base of a mountain wall. Only a day from the relative bustle of Natales, this was a place that gave us everything we had dreamed of in Patagonia. Dolphins played in the caleta, Andean condors soared over the high mountains across the fjord, there was good hiking through the Dr. Seuss-like vegetation on the hillside above us, and we had a perfectly sheltered nook where Galactic could wait out a few days of driving snow while held in place by four lines tied to massive trees.

Anchorages like Caleta Mousse are the key to Patagonia. There are hundreds of little coves where the deep water allows a cruising boat to tie securely to the trees, often only a few feet from the shore. With high trees blocking the wind, and shorelines fore and aft, there is nothing in the weather that can bother a boat tied in to points onshore in these places.

But getting in and out of such protected spots is when things can go awry.

And so it was when we tried to leave Caleta Mousse. The morning was calm. I started rowing around the anchorage, untying our lines from the trees while Alisa and Elias pulled them to Galactic. With the lines retrieved, we started to pull the anchor.

It was then that we realized the shape of the mountain wall west of the caleta was perfect for pulling the wind down into the anchorage. All we knew on this morning was that when the anchor was just about up, we were suddenly hit by williwaws that made the water smoke. Alisa quickly spooled out chain, but it was no good. There wasn’t enough room to swing. We needed shore lines again.

I jumped into the dinghy and rowed like a madman to the upwind side of the caleta, a shore line tied around my waist. Once I had finally tied us off to a tree I looked back in relief. And then I saw a sight that made all my confidence evaporate, a sight that turned all my dreams of sailing through Patagonia into so much fluff blowing in the breeze.

A williwaw had Galactic in its teeth and wasn’t letting go. I stared at the underbody of our floating home while the mast leaned over at a crazy angle. Surely we weren’t so close to the shore that the masthead was over the rocks? Alisa was desperately trying to power into the wind blast. She was trapped at the wheel and unable to go up to the bow to tie off the shore line that would solve all of our problems.

It was only for a moment, but that moment stretched out in the suspense of what might happen. Standing there on the beach, the adrenaline of the row ebbing from my veins, I felt my shoulders slump at the knowledge that I was nothing but a spectator. For that one moment, I just stood on the beach and watched whatever would happen, happen.

Of course, the williwaw passed, and Alisa soon had the shore line tied off. We agreed that we would have to be more cautious about picking our moments to leave anchorages. And Alisa reported to me, with some wonder in her voice, that through it all the boys hadn’t evinced any kind of worry. They had been down below, laughing their heads off and cheering the wind on to give them a better ride.

Complete ignorance at what might really go wrong — it must be one of the greatest blessings of childhood. And our determination to see Patagonia as more than a series of confrontations with outrageous conditions? That was getting a little threadbare.

When the weather forecast was ideal, we pulled the shore lines and slid out of Puerto Profundo at first light. In the weeks since we left Natales, I had become intoxicated with how sailing through Patagonia was such a linear adventure. It wasn’t at all like the incredibly open spaces that we were used to from the Pacific. We were always hemmed in on two sides by mountain walls, so the only decision open to us was whether to move forward or go back. Which was no decision at all. We traveled farther and farther south. The days grew shorter with every passing mile, and the scenery grew more and more splendid. The sailing was fantastic, with a scrap of jib being all that was needed to see us speeding along on the prevailing northwest wind. On Galactic, family life slowed down as we found the natural pace of living through the long nights of winter without any of the distractions of the Internet or television to dilute our experience of the place and the season. I was in heaven.

And things were about to get even better. From Puerto Profundo we motored into the Strait of Magellan. As we made the turn into the western entrance, the sun cleared the clouds to illuminate the snowy mountains on either side of us. Who couldn’t feel the moment? We were at the very spot where Ferdinand Magellan became the first European to sail into the Pacific and, finding it on the same sort of calm day that we were enjoying, gave it the name that we all know it by.

That night we tied in at Puerto Angosto, where Joshua Slocum anchored Spray during his first solo circumnavigation of the globe. Slocum was at Angosto for something like a month, and made six unsuccessful attempts to set off from that spot before the weather let him get away.

We were sailing legendary waters.

The eastern Strait of Magellan is a nightmare of huge tides, exuberant winds and few good anchorages. After Magellan made it through the strait, attempt after attempt to repeat his route failed. Luckily, cruising boats can leave the strait around Cabo Froward, the southernmost point of continental South America, and continue along the fjords into the Land of Fire — Tierra del Fuego. We followed that path, and found we had the whole spectacular cruising grounds pretty much to ourselves. There were a few fishing boats around, and every morning we came up on the Patagonia cruisers SSB net and emailed our position to the armada. But even with those occasional reminders of the rest of humanity, our family mostly seemed to be carrying our own envelope of solitude around with us, from anchorage to anchorage, through crystal day after crystal day.

The snow line came down to the sea. The mountainous islands through which we traveled were majestic, remote and polar. Each anchorage was mysterious, and a study in ice and snow and cold when compared to our expectations of what a normal cruising anchorage should look like. The best anchorages were surrounded by hills where the family could walk in the snow and build snowmen, and the boys could indulge in the limitless joy of throwing snowballs at their captain and generally causing a ruckus.

After we entered Canal Beagle, conditions seemed to be building to more and more delirious levels of thrills. Our destination of Puerto Williams, Chile, the southernmost town in the world, was less than 100 miles away. With every mile, the sailing got wilder, the mountain scenery more spectacular. It felt like we might reach takeoff before the trip ended, might attain some otherworldly plateau of sailing adventure that we couldn’t have imagined before we set off but which became obvious, even inescapable, to us now. Fully half of the anchorages we investigated were frozen over, and we got used to the sound of ice grinding against our hull at night with a change in wind or tide. Turning a corner with Galactic might bring us face to face with a cathedral of glacial ice spilling over mountain buttresses to the sea.

And then the day arrived when we came out of the metaphorical cold. After months of wandering on our own, we called the Puerto Williams armada on the VHF to give notice of our arrival. We pulled into the “uttermost yacht club in the world,” a 1930s-era freighter named Micalvi that has been scuttled in a shallow inlet to make a clubhouse and dock for visiting sailboats. We found about 40 boats rafted to the ship, most of them left for the winter while their owners flew home. Our arrival bumped the number of inhabited boats to six. We found ourselves immersed in a warm social scene of like-minded people who shared the bonds of common experience.

I can’t say enough about choosing winter for our first visit to the far south. Winter makes everything lonely and mysterious, the way Patagonia should be. We approached the whole undertaking with humility. We were confident, but we assumed nothing. We prepared adequately, and we consciously worked at making good decisions. Our goal was to make it look easy, with as few close shaves or harrowing tales as possible. And more than that, we wanted to have a blast. We wanted Patagonia in winter to be a really good time.

That part worked. The kids had a blast. Alisa had a blast. I had a blast.

And the sense of moving through the out-of-the-way corners of Patagonia independently? The feeling of choosing our pace and taking responsibility for everything? The relish of dreaming about a trip like this and then doing it, and finding ourselves equal to it?

It’s no wonder people find the sailing life so hard to give up.