Once found only in the ascetic realm of single-handed sailing, self-steering gear has become ubiquitous on cruising boats, even fully crewed ones. That’s because a self-steering unit serves as an additional hand that possesses relentless concentration at the helm; subsists on only amps or lubricants; and, if properly trained, does what’s asked of it without question or complaint.

Reliable remote control of the helm relieves the fatigue and monotony of following a compass course at night. It allows time for sail changes and adjustments; horizon sweeps for ships; attentive navigation; and that quick dip below to check the bilges and grab a hot drink. Without question, self-steering makes for a more relaxed, enjoyable and safe voyage.

But the debate over which kind of self-steering is best for a sailboat — electric or windvane — rages on. I may be an old-fashioned belt-and-suspenders kind of sailor, but I believe both systems have their different strengths and weaknesses, and therefore complement each other. In other words, any vessel that is configured in a way that can accommodate both methods should do so.

In this scenario, the more robust mechanical sailboat windvane would be employed in heavier weather, while the electric autopilot would be used in light airs and under power, where directional corrections are provided not by the wind, but by a fluxgate compass. It is important to understand that while the electric autopilot maintains a steady compass course, a windvane is set to maintain a desired angle off the apparent wind, and therefore will follow any wind shifts or changes in wind velocity. While this does keep the sails perpetually in trim, the course must be monitored closely when in confined waterways.

That said, if forced to choose, I would go with the mechanical windvane, hands down. Vanes don’t rely on the ship’s electrical power supply, which serves as the last link in a long chain of delicate electrical components and breakable mechanical parts. Across the range of types and brands, mechanical windvanes generate amazing power in rough conditions (when needed most), coupled with notable durability. Almost 30 years ago I purchased an already well-used Aries windvane. It has faithfully followed me from boat to boat, and around the world, with clear indications that it will outlast me. On the other hand, I have an overflowing box of spare parts cannibalized from the many electric tiller-pilots I have chewed through in that same period.

Types of Sailboat Windvanes

Introduced by the indomitable Blondie Hasler, founder of the OSTAR solo transatlantic race in 1960, the original sailboat windvane consisted of a direct coupling of a horizontally rotating (vertical axis) vane to a trim tab on the aft edge of a transom-hung rudder. Once the vane was fixed to the desired angle off the wind (using a round base plate with notches spaced at 5-degree intervals), any course change rotated the large vane like a weathercock. This in turn twisted the tab to one side of the main rudder, driving the rudder in the opposite direction, thus bringing the vessel back on course. The advantage to this system was its ease of construction and low cost, but it was best adapted to the waning style of transom-hung rudders. Also, a large vane was required to harness sufficient wind to power the trim tab. Therefore, especially in light airs, the tall, heavy vanes often reacted more to the yaw and roll of the vessel than to the wind, resulting in erratic meandering.

However, from this early and rudimentary concept, two sophisticated yet distinct types of vanes evolved: the servo-pendulum system (SPS) and the auxiliary rudder system (ARS). Both SPS and ARS systems employ a counterweighted horizontal- or vertical-axis wind vane to activate an appendage in the water, but the similarities end there. (To confuse the issue, there is now a hybrid system called the servo-driven auxiliary rudder, or SAR. But by first addressing the two basic concepts, a clearer understanding of this marriage of ideas will emerge.)

The SPS system — best represented by brands such as Aries, Cape Horn, Fleming, Monitor and Sailomat — uses the movement of the windvane to horizontally turn an independent servo-rudder (essentially a separate oar or paddle) that is deployed into the water. As the boat moves, the laminar flow of water presses against the positive lead on the servo-rudder, generating sufficient power to aggressively swing the servo-pendulum, or windvane, in one direction or the other.

While it is the power of the wind that directs the angle the servo-rudder presents to the passing water, it is boat speed through that water that exerts the considerable pounds of pull on the lines that run from the servo-rudder and through a series of turning blocks, ultimately connecting to the tiller (or, in the case of wheel steering, a drum in the center of the wheel). More simply, the servo-rudder does not turn the boat; it pulls on the tiller or rotates the wheel, which in turn moves the main rudder.

Perhaps the main drawback to this concept is the limited throw of the lines, as the distance of arc through which the pendulum swings is limited to the width of its supporting frame, an average of approximately 10 inches. This is no issue when connected to a tiller because one can fix the lines at the optimum point on the helm: high for more power, lower for a greater turning angle. But depending on the stop-to-stop ratio of a wheel steering system, the length of pull may not be sufficient to effectively control the vessel. This problem can be exacerbated by center-cockpit designs, as longer line lengths may stretch more, further limiting the effective length of pull.

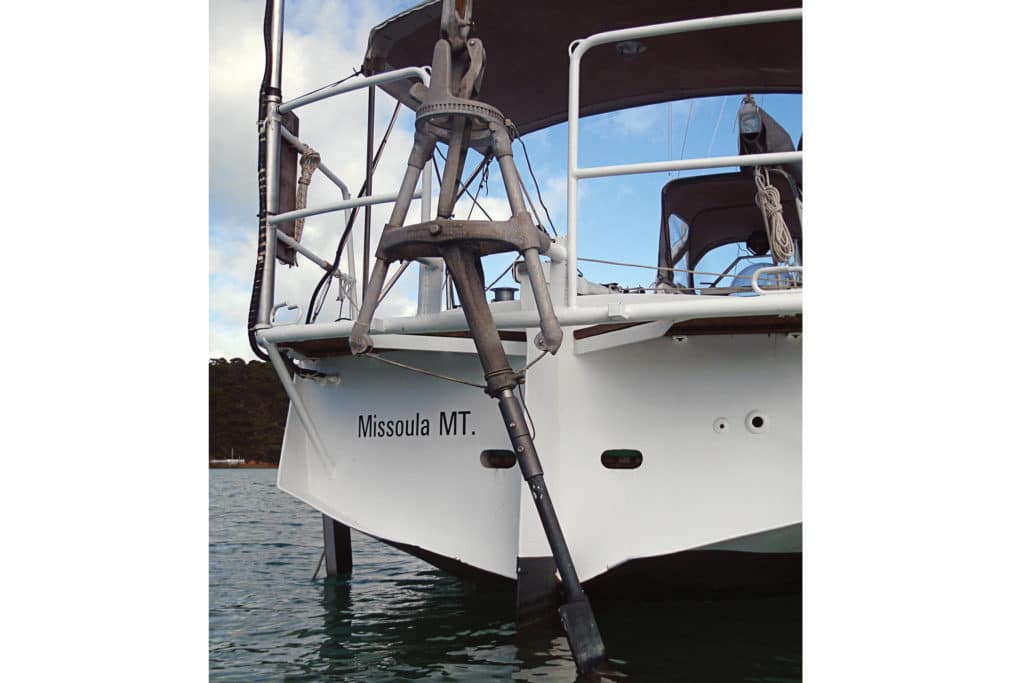

The ARS system, best represented in the market by Hydrovane, employs an altogether separate appendage to steer the vessel. The boat’s main rudder is usually fixed amidship (or angled slightly to offset a lee or weather helm) and a second, auxiliary rudder, directed by a windvane, takes control of the steering. Thus, it is not only a self-steering device, but can also serve as an emergency rudder. Considering that all four of the Mayday calls I monitored on one of my Pacific crossings related to steering failure, this redundancy has considerable value. Because of the forces placed on this rudder it must be robust in construction, well fixed to the vessel, and of sufficient design and size to handily maneuver substantial tonnage.

Pros and Cons of Sailboat Windvanes

There is a heated online debate among some of the manufacturers and distributors of the respective systems, each dismissing the supposed advantages of the other’s design concept while touting their own. I have sailed with both servo-pendulum designs and auxiliary rudders and found both to be practical and reliable; the final decision, to me, comes down to the type of vessel to which they will be attached, the steering system onboard, the conditions of sailing most likely to be experienced and the budget. In my opinion, the auxiliary rudder is more sensitive in light air, which is the average condition found in many recreational sailing areas. I’ve found the servo-pendulum model to be rock steady in conditions so rough that the average helmsperson would be exhausted within an hour.

But there are advantages and disadvantages to each approach. For example, the auxiliary rudder windvane has no provisions for being lifted out of the water to clear flotsam and seaweed; it can affect the backing characteristics of a vessel; and there’s no dedicated, engineered, breakaway “weak spot” when colliding with something like a submerged log. (In such instances, most servo-pendulum rudders simply flip up out of the way, and are popped back in place with the pull of a line.) On the other hand, auxiliary rudders don’t require lines that obstruct the decks and cockpit, a significant advantage depending on the placement of the helm.

To the latter point, perhaps too much is made of the difficulty in fixing, releasing and adjusting the tension of the lines on an SPS windvane. I corrected this problem with a $5 double jam cleat. Instead of using the typical link in a chain to connect to the tiller, I run my lines through an eye bolt on the tiller and back to the jam cleat. I can ease or tighten the lines balancing friction with precision; introduce infinite increments of bias to help balance the boat; and even when under tremendous pressure, immediately release the lines in an emergency situation.

A subtle but potentially important advantage of the SPS windvane is its natural aversion to broaching. As a steep wave slams into the quarter, the vessel can violently swing sideways. However, this same sudden sideways force pushes the servo-rudder in a direction that immediately tries to turn the boat back down the face of the wave. But even that point could be countered with the claim that by fixing the large main rudder in place, as in an ARS, substantial lateral stability is added to the vessel, thus minimizing any penchant to broach.

When mounting either system, the latest sailboat design trends — open, aft-entry cockpits and drop-down transoms — present new challenges. Hydrovane makes the unequivocal claim that its ARS windvane can be mounted off-center without affecting performance. Offsetting the vane opens access to the sugar scoop and/or the boarding and swim ladders. But as drop-down transoms, in particular, become ever beamier, there is less flat and fixed space available for robust windvane mounting. Depending on the stiffness of the vessel, one would not want to push the vane too far outboard for fear of lifting the auxiliary rudder clear out of the water on a heavy heel.

All SPS manufacturers stress the importance of meticulous centering during initial installation. Adapting to these new transoms, Monitor has introduced the SwingGate system to its windvanes. This is essentially a pivoting pushpit, much like a garden gate, with the vane attached. When the gate is open the boarding platform or swim ladder can be accessed, and when the gate is closed the vane sits firmly fixed amidship.

While completely appropriate for trimarans, windvane steering is not well suited for catamaran designs due to the dual rudders and high bridge-deck clearance.

As to pricing, there is no denying that the basic ARS units cost from 25 to 40 percent more than SPS models. Acting as the boat’s main rudder demands that the auxiliary rudder and mechanisms be constructed from heavy, high-quality materials. But if one chooses the swing-gate option, the additional cost of the gate structure must also be factored in.

Summing Up Self-Steering

When choosing a self-steering system for your sailboat, closely assess the design features of your boat and the conditions you will most often encounter. If you intend to make any kind of extended passages, consider a high-quality mechanical self-steering unit, possibly coupled with a lighter electrical system. Often, the two can be combined, offering the precision of fluxgate steering with the power and toughness of mechanical systems (see “A Hybrid Self-Steering Solution“).

After the initial expense of purchase and installation, there will be no piece of equipment on your vessel more prized than your mechanical self-steering. I don’t know of a single long-distance sailor who has given a name to the roller-furling system, nor of one who has not named the windvane. Be it SPS or ARS, called Esther or Otto, trust me, out there on the Big Blue you will have many long and meaningful conversations with it.

But like all relationships, this one requires practice and patience. First and foremost, do not ask the windvane to make up for sloppy sailing. Balance your boat, starting with waterline trim. Keep the weight out of the ends and ensure that the sails are appropriately sized, set and trimmed to the conditions. Excessive heel is not only slow, but places the boat on lines that the designer never intended, resulting in poor tracking. Ensure that the windvane is not blanketed by superstructure or fed turbulent air via barbecues, solar panels or davits. Experiment with different settings, such as blade angle and line tension, to understand and optimize performance in various conditions.

Models that employ a mix of metals should be disassembled, cleaned and lubricated regularly to minimize electrolysis. When reassembling, use a high-grade barrier cream on all fasteners.

All models benefit from an occasional bath of scalding-hot fresh water to dissolve any buildup of salt, minerals and solidified grease.

And finally, for those concerned that these protruding, industrial-looking structures may ruin the lines of an otherwise lovely vessel, remember: “The rougher it gets, the better they look.”

Windvane Manufacturers

Aries Vane Gear ariesvane.com and ariesvanegear.com

Cape Horn Marine Products

Fleming Marine

Hydrovane International

Sailomat USA

Scanmar International

Voyager Self Steering Inc.

Windpilot

Two-time circumnavigator Alvah Simon is a CW contributing editor. This article first appeared in the July 2014 issue of Cruising World as “A Vane to Steer Her By.”