The last few years have been hectic ones for retired business executive and offshore sailor Mark Gabrielson, though his good-natured, ever-curious demeanor belies it.

In 2011, not only had he embarked upon earning a master’s degree in maritime history through the Harvard University Extension School, but he’d also begun research on a book he wanted to write about the local legends of Deer Island, Maine — the brawny 19th-century crews who successfully defended the America’s Cup in 1895 and 1899. And there’s something else: Skipper Gabrielson was preparing Lyra, his 1976 Hinckley Sou’wester 50 yawl, to compete in that year’s Marion-Bermuda Cruising Yacht Race in the celestial navigation class.

The traditional, complex form of navigation had long ago taken hold of and fascinated Gabrielson, to the point that he had a comfortable working knowledge of it and enjoyed using it whenever he could.

For the race, Gabrielson enlisted friend and talented celestial navigator Steve Bussolari from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, while he focused on prepping the boat and crew. Lyra didn’t take the top spot in her class, but a good time was had by all.

Meanwhile, Gabrielson’s book project and academic research accelerated. He sought out and was granted a tutorial with John Hattendorf, the nation’s leading maritime historian, to continue his master’s degree work at the U.S. Naval War College Museum in Newport, Rhode Island.

Yet despite these demands, and with salt still running persistently in his veins, Gabrielson and his crew decided to enter in the celestial class again for the 2013 running of Marion-Bermuda. Lyra’s crew, the same bunch who’d assembled in 2011, did much better, winning the Kingman trophy for the best combined corrected time for a yacht club team — after the commodore of the Beverly Yacht Club realized his team won the award in error, and insisted the trophy be reallocated to Lyra and her Blue Water Sailing Club teammates.

Fast-forward to the summer and fall of 2014, when Gabrielson’s devotion to celestial navigation and knack for digging up historical facts took yet another serendipitous turn — just as the ink was drying on his Deer Isle’s Undefeated America’s Cup Crews: Humble Heroes from a Downeast Island.

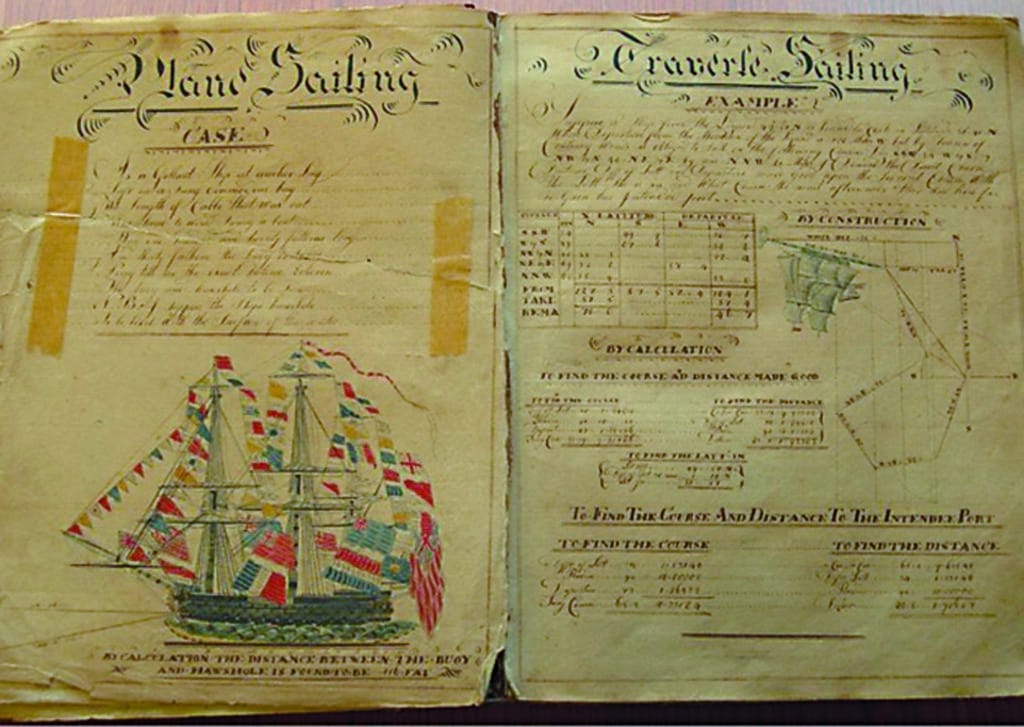

One day, while Gabrielson and Hattendorf were rummaging through the dusty archives of the War College Museum, they pulled open a neglected drawer. In it lay a workbook with ornate calligraphy, dated 1807. The discovery of William Carter’s Navigation Book, Givet Prison, France, was a real breakthrough for Gabrielson in his master’s research. “When I opened that book, it was a holy-cow moment,” he said. “I literally could not sleep that night.”

According to Gabrielson and Hattendorf, the material in the workbook — real-life celestial navigation problems and their mathematical solutions — turned out to be the sole proof that British prisoners of war like Carter, stuck for years in a dark and damp prison in Napoleon’s France, were trained in navigation to a level that in their homeland was almost exclusively reserved for the British aristocracy.

After further research, review and refinement, the book, whose journey to the archives remains a mystery, was put on permanent display as a digital exhibit at the War College Museum. “Had there been no Napoleonic War, or if they hadn’t suffered capture, these British sailors would never have received the valuable education they did through the POW school in France,” Gabrielson says.

Aside from the significance of the find and what it underscores about British command of high-seas trade in the 19th century, it resurrects a newfound appreciation for the sophisticated understanding of navigation that seamen of that age and earlier possessed and routinely exercised.

“The William Carter journal is, indeed, an inspiration to anyone who has attempted, or even feels they have mastered, celestial navigation,” Gabrielson says. “Most of us now use computer software to reduce our sights onto a plotting sheet. The more ‘traditional’ of us still use the Nautical Almanac and Sight Reduction Tables for Marine Navigation, where most of the mathematics behind sight reduction is worked out in tabular form. Carter did all of the math himself. His approach required that he have a strong background in trigonometry. He probably learned trigonometry in the prison school, and then went on to apply it in his navigation problems. That deeply impressed me, and will anyone else who looks at the journal. He was a pure celestial navigation problem-solver — no shortcuts.”

Indeed, spanning centuries and oceans of distance, there’s little doubt that the persistent, tenacious qualities of both sailors somehow put one on a course to discover and shine a light on the other.

Elaine Lembo is a CW editor-at-large.

Editor’s note: While Lyra didn’t participate in the June 2015 Marion-Bermuda Race, Mark Gabrielson, a trustee of the event, accompanied the fleet and handled communications and safety. In his downtime, he assists Harvard physics professor John Huth in teaching Primitive Navigation, a course about navigation methods used before GPS and iPhones.