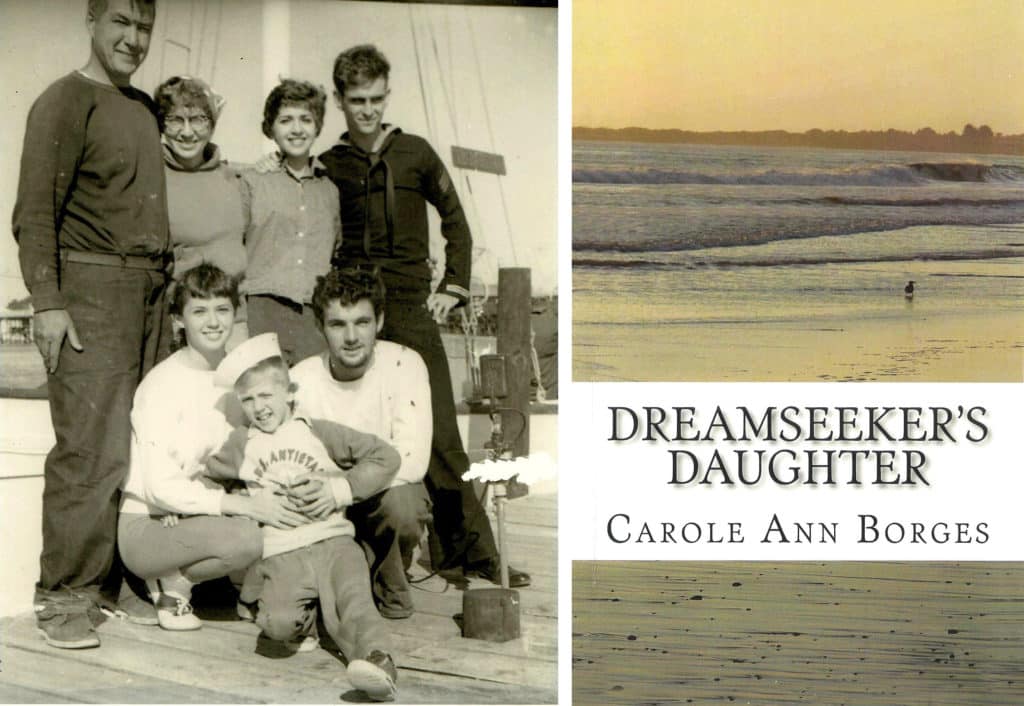

If I ever meet Cruising World columnist Cap’n Fatty Goodlander, and I hope I do, the first thing I’ll say is “Oh, you’re Carole Ann’s brother!” I will say this with all due respect, of course. I’m a huge fan of Fatty’s stories and his irreverent and lusty humor. But after reading Carole Ann Borges’ Dreamseeker’s Daughter (2013; CreateSpace; $15), I am at least as big a fan of her writing. I liked the book so much, I contacted her to ask for an interview, and to my delight, she readily agreed.

Over the phone, from her home in Tennessee, Carole Ann told me that when Fatty’s book Chasing the Horizon came out, she was very proud of him and loved the book, but she felt something was missing. “The feminist in me rose up,” she said. “I thought there should be more about my mother’s heroic effort.” Carole Ann felt her mother wasn’t given enough credit for the critical role she played in their cruising adventure. Fatty’s book focused more on their charismatic father, Edward.

Fatty was just 3 years old when the family moved aboard the Alden schooner Elizabeth in 1953. Carole Ann was 10 years older. She was the one at her father’s side in the boatyard as they desperately tried to breathe life into the rotting hulk of a boat, while her mother, Marie, took care of Carole Ann’s younger sister, Gale, and baby Fatty, then known as Gary. When a shambling Irish setter named Jerry joined the family, Marie decided “Gary” sounded too much like “Jerry.” Whenever she called Gary’s name, the dog came running. She decided it was easier just to change the baby’s name. So Gary was nicknamed Timmy, and remained so until much later, when he became Fatty.

In 1950s Chicago, Carole Ann told me, there were no women on boats. “We were really pioneers,” she said. People were amazed to see a teenage girl deftly handling the helm of the 50-foot Elizabeth. “I was the deckhand and first mate,” she said. But she said her mother was “the real hero” of the story, and Dreamseeker’s Daughter is as much a tribute to her as it is a sailing adventure.

If you’ve ever lived aboard a sailboat on the hard in a filthy boatyard, you know only love could keep a woman and her three children, including a toddler and a young teen, living aboard for four long years, particularly through the frigid Chicago winters. The Goodlanders had no head, no running water, not even a functioning galley sink. Marie collected the dirty dishwater in a pan and had to carry it out, up the companionway ladder and across the deck to the stern, to empty it. Still, the family persevered. It was Edward who kept the dream alive. He envisioned Elizabeth sailing to Tahiti, where there would be friendly natives, warm sunshine, and bananas growing on trees. He dreamed of freedom and adventure, and Marie believed in him. If she or the children complained about the miserable conditions in the boatyard, Edward would gently remind them of the privations of the whalers and how the family’s situation was so much more fortunate, and they would end up feeling guilty for complaining.

But as Carole Ann grew older, she found herself ostracized and bullied in school. The other kids called her “Sunken Sailboat” or “Tugboat Annie.” She hated having to take sponge baths and not having a shower. Marie was having a tough time keeping Timmy out of trouble, too, now that he was a toddler. In desperation, she suggested to Edward that they get an apartment, just temporarily, until the boat was back in the water. He was not receptive:

“‘Move off the boat?’ Dad gasped, like she was suggesting we migrate to the moon. ‘You’re talking mutiny, Marie.’”

The winter of 1956 was the worst. Edward removed a dry-rotted 6-foot section of the hull and covered the hole with a tarp. The icy wind whistled in. Everyone was miserable. But as often happens on adventures, especially those involving a boatyard, just when all seems irretrievably hopeless, the trials are almost over.

In October of 1957, four long years after they moved aboard, Elizabeth was finally launched. Carole Ann was 17 by then, and the whole family was excited to be finally getting underway. With the children out of school, Marie seized the opportunity to share her love of history with them, and there were plenty of historic sites to visit along the Mississippi. “What a wonderful life we had on the boat,” Carole Ann said. “We couldn’t have learned more in school, that’s for sure.” They stood in the trenches at Vicksburg, Mississippi, visited historic plantations on the Natchez Trace, and ate jambalaya shrimp in New Orleans. “The thrill of getting up every morning and opening that hatch, it was like a movie,” she said. Compared with living in the city, the beauty and serenity of the river were magical.

There was plenty of excitement on the way, and not all of it was good. In Cairo, Illinois, a flood caused a logjam, and Carole Ann endured an exhausting night with her father, shoving enormous logs away from Elizabeth’s hull. The bottom of the river was unreliable for anchoring. There were barges to dodge and fierce currents, and Elizabeth sometimes needed repairs. There were the dwindling finances to consider as well. Carole Ann helped out along the way by working in dime stores and drugstores, while Edward painted signs.

The love between Edward and Marie was profound. Overcoming the obstacles of sailing with children enhanced their relationship immeasurably. Marie beamed with pride when Edward hit on the idea of getting an old telephone pole for a mast in Pensacola, Florida. They had seen their first palm trees; surely the South Seas were just around the corner. Carole Ann had accepted the proposal of a young man in New Orleans, but the budding relationship couldn’t withstand the swarm of Navy men she found in Pensacola.

There were heady times for the whole family as they gunkholed along the Florida Panhandle. In Apalachicola, with a hurricane coming, they headed out to sea to ride it out because Elizabeth’s 7-foot draft was too deep to go up-river for safety. Sadly, they ran aground just a few hundred yards offshore, and Elizabeth’s keel was irreparably damaged. They limped over to St. Petersburg, leaking all the way, but there the journey came to an end for the time being.

Carole Ann discovered writing in early adulthood, as Fatty did much later, but her first love was poetry. After a brief stint at Salem College in Massachusetts, she was accepted into graduate school at Vermont College on the strength of her unpublished poetry-book manuscript. She earned an MFA in creative writing in 1985 and went on to publish her poems in many important literary journals.

Beth Browne lived aboard a CT 37 on Bainbridge Island, Washington, and in San Diego. She currently weekends on a custom-built 33-foot sloop in Pamlico Sound, North Carolina.

Editor’s Note: On August 2 — with Cap’n Fatty and dozens of other loving family members at her side — Carole Ann Borges succumbed to cancer at age 74.