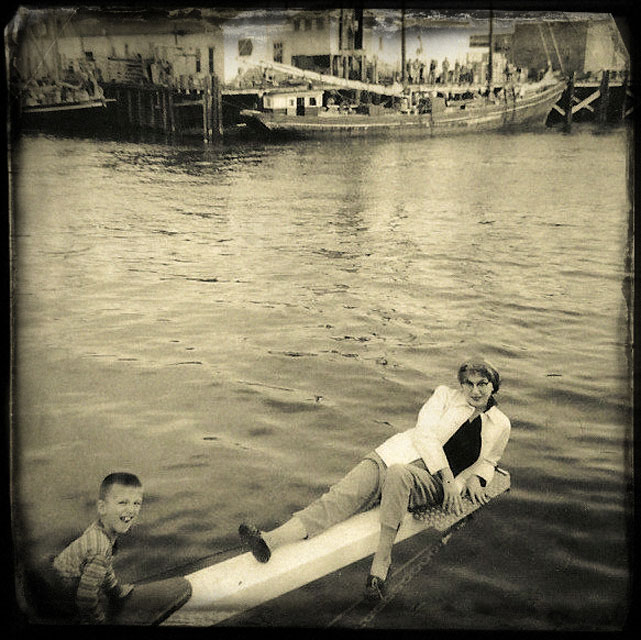

Marie Goodlander

It’s a cold, windy, wintery morning in Chicago, and our 52-foot schooner is on the hard and half buried under tarpaulins and snow. It’s the mid-1950s. I’m young, and I’m huddled over a steaming coffee cup. We’re midway through a major rebuild: Many planks are missing from the hull; only a few new ones have been steam-bent back into place. My mother is making a bacon and cheese omelet on our roaring Shipmate coal stove. The rest of us are gathered at the galley table. Father is preparing to head off to work, and my two sisters, Carole and Gale, are taking turns yanking each other’s ponytail. All is well.

Unexpectedly, we hear a noise outside. There’s a flutter of light as the tarpaulin is lifted.

It seems a young couple is touring the shipyard, and moments earlier they’d come across the majestic Elizabeth. The boat is massive. Built in 1924 by the Morse Brothers of Thomaston, Maine, she towers over the rest of the boats in the yard.

“Lookee here, honey,” the man says to the woman. “Some fool’s trying to fix up this ol’ schooner. Ain’t that ambitious!”

The man ducks under the scaffolding that rings the hull, stoops down, unties the snow-dusted tarpaulin, spies the large gap in the missing planking, and suddenly finds himself standing upright in the middle of our main cabin and happy little home.

He’s as shocked to see us as we are to see him. My mother waves an eggy spatula in his direction and says, “How do you like your eggs?”

His jaw drops in total amazement, Without thinking, he calls out to his woman in the snow, “My god! They’re eating in there!”

Like a jack-in-the-box, he disappears from view, leaving the tarp flapping and the cold air flooding in. We can hear him hastily scurrying away.

“Scrambled,” says my father.

“Runny,” says Carole.

“Letting in the cold—that boils me!” says Gale.

I’m too young to be fast, but I get there. “Sunny side up, says this son!”

“Those are some good yolks,” says my father.

I’m squirming in my seat, so excited that I have to be careful not to pee. I’ve got one! “Don’t egg me on!” I say.

Everyone laughs. Lubbers are so weird! It’s useless to attempt to understand them. We believe it might be all the dirt they inhale or the automotive exhaust fumes.

We’re different. We’re not just a family; we’re a crew, a tribe, a very small nation of sailing revolutionaries. We’re odd, and happy to be so. For many years afterward, whenever the going would get weird ashore, we’d sing out to each other, “My god! They’re eating in there!”

My mother and I draw pictures all day at the galley table. We hold them up to show to each other and then hug because we’ve produced such excellent examples of artistic expression. I’m Picasso; she’s da Vinci. The world will soon know of us. We can hear the applause building like summer’s thunder in the distance.

Carole and Gale come home, climb up the topsides on the lashed-to-the-rail ladder, and fling themselves (and their schoolbooks) into the adjacent dinette seats. We hold up our pictures one by one, and they always find something to praise.

This is just one of my 10 billion childhood memories, but my mother clings to the scene down through the decades with utter clarity. “Remember when we used to draw pictures at the galley table of the Elizabeth, and then the girls would come home?” she’s said to me throughout her long life—even as orderlies wheel her back inside her room or she’s taken off for hip surgery or she’s just adrift on the whimsical clouds of memory that now sometimes befuddle her 94-year-old brain.

A year later, though I’ve grown, I’m still not allowed on deck during a blow. It’s rough, and our bow plunges in the troughs. The wind moans through the rig. Deck planks creak. “Marie!” my father calls urgently down through the companionway. “Get your foulies. I have to reef!”

I’m supposed to stay in my bunk, which is silly. I’m practically a man. I creep aft, climb the companionway stairs, and peer into the wave-tossed cockpit. I can see her at the wheel through the sheets of spray: my mother, my fellow artist. She looks so brave. A wave slaps her and displaces her thick glasses. She’s surprised but shrugs it off. “Come up! Come up!” my father is shouting. “Good! Hold her head to wind. Just a few more seconds, Marie!”

I scurry back into my bunk before they spot me. All is well again. They have it under control. King Neptune is a family friend. He might toy with us in order to teach us certain lessons, but he’s really a benign, loving soul. We’re safe. At sea, we’re home.

And then I’m 7 and the man of the house while my father delivers a fishing schooner to Campeche, Mexico. I’m awakened in the dark. They have flashlights and are whispering. Father warned me there’d be times like this. I must stay calm and show no fear. I strut aft. The Goodlander women were worried about being raped. I wasn’t sure what “being raped” was, but it didn’t seem to concern me.

“He’s right next to the boat!” my mother cries out in fright. “In the water!”

“Who is?”

“The guy!” says one sister. The other backs her up: “He really is!”

I was scared, not of rapists but of bogeymen. I wasn’t sure what they were, either, but I knew I didn’t want to find out. Still, I was a man, and I had a job to do. I crept outside into the cockpit, slithered tentatively over the starboard coaming, and peered over the caprail down into the dark, scary, sloshing space between the boat and dock. Debris was trapped there: seaweed, logs, bottles. The boat was moving in the greasy swell, and the fenders groaned against the pilings. There was no moon, yet barnacles glistened. Crabs held up their claws. Silverfish slid out of sight.

I had to calm my stomach.

I leaned far over the rail to get a better view. I wanted desperately to report no rapist, no bogeyman, no problem.

But then the impossible: My blood froze when the rapist took a long, loud, deep breath.

I started screaming, so loudly that I barely noticed Carole flying past me and dashing down the path for the police.

Afterward, we had a good laugh with all the rescue personnel, cops, and firemen who’d discovered the turtle partially wrapped in a fishing net and thus caught between the boat and the dock, barely able to breathe. They hoisted it out, cut the net away, and set it free.

On another day, I return to Elizabeth after the mile-long trudge from the Mary A. White grammar school. At first, I think no one is home. Then I hear faint crying. I creep into the forecastle. My mother is slumped over her manual Royal typewriter. Her 400-page manuscript is scattered on the cabin sole. She raises her head. Her nose is running. She looks weird.

“I’ll never be published,” she says.

I sit beside her, put my arm around her, and say nothing. Life is hard sometimes. We just accept it; we allow it to wash over us. The tears flow. I attempt to imagine what it would be like if she ever were published, but I’ll have to wait many decades for her to receive her first acceptance, at the age of 88—and see that fierce fire of ferocious pride glowing in her eyes.

I’m older now—perhaps I’m 10 years of age. My father and I are working in Clearwater, Florida, to erect a giant swiveling bucket alongside a highway for a brand-new company called Kentucky Fried Chicken. The manager dashes out of the fast-food restaurant and shouts, “Elizabeth is sinking! There’s no shore power, and the pumps can’t keep up! Hurry!”

Within minutes, we’re in our old jalopy, heading back to Slip No. 7 at Vinoy Basin, in St. Petersburg, Florida. But the traffic is heavy and our car slow. It takes an agonizingly long time. We make the last turn on two wheels, expecting to see a crowd of gawkers milling around the sunken wreck. Instead, we see only Marie, and she’s manning a giant cast-iron pitcher pump that nobody but a real he-man can use, and she’s slowly pumping, stroke after stroke, with its eight-foot-long rusty handle.

She, too, is made of iron. She’s saved the boat, saved our lifestyle, saved our dignity. She’s the stout sea anchor of our sea-gypsy family. My father is grinning a shy, grateful smile as he shuts off the car. “She’s got a set of ovaries,” he says in admiration.

Fast-forward 50-odd years. I’m on the phone with her. We call her the Sea Siren now. She wants to visit. “I’ve never sailed on Ganesh,” she says, as if that explains everything.

I’m a man of logic. I have some sense. I’m not a fool, or leastwise not normally. For decades while circumnavigating, I’ve been conversing with various doctors who keep telling me her death is imminent. Yes, she’s already fallen a number of times. Once, she broke her hip, and an arm, too. Yes, there are pins and rods and bolts holding much of her frame together.

I consult with her doctors and her friends and her neighbors. They all say, reluctantly, that she’s too far gone, too old and frail at 94 to journey anywhere. And of course, sailing is absolutely out of the question.

“Do you want to kill her?” one friend asks me forthrightly.

Did I mention that she’s now legally blind?

So I know what I’m supposed to do: tell her no. Tell her that her dream of sailing aboard Ganesh is just folly!

But during my youth, there were a million times when she was supposed to tell me no—but she always said yes. She’s the one who taught me to be so free, free, free.

I snatch up the phone, dial her number in Santa Cruz, California, and shout, “Great! Wonderful! Of course, we’d love to have you, Sea Siren! We’ll beat up the Sir Francis Drake Channel, have Thanksgiving at Haulover Bay on St. John, and then set up the twin downwind poles for the run back to Cruz Bay. How’s that sound?”

It took us a while to prepare: We removed the Monitor windvane so it’d be easier for her to clamber aboard, added PFDs to the dinghy, and identified strong handholds in all the areas where she’d be likely to sit. My biggest worry wasn’t the trade-wind seas but rather a steep ferry wake that might catch her totally unawares.

On the second night, we take her ashore by dinghy to Caneel Bay to see if she can seduce “one of them rocking fellows,” as she put it. Perhaps to bolster her self-confidence, she says to me, “I want a martini, Timmy.”

Timmy was my childhood nickname.

“I want a martini, too,” chimes in Carolyn, my wife.

“Me three,” says Morgan, my brother, who brought Marie here to the islands from the States.

I’m worried. It wasn’t easy getting her from the swim platform into the dinghy. Now they’ll all be drunk as well.

I voice my concerns. “Don’t be so uptight,” my mother says breezily. “What’s a martini or two? That is, before I switch to the Cruzan rum!”

Oh, dear.

Ashore, my mother’s on a tear. She drags me on the dance floor and starts to make moves no son should see.

“She’s still got it!” laughs Carolyn, grinning behind her champagne glass.

Eddie Bruce, a local St. John drummer, is in the band. My mother has always been attracted to drummers, and she says to me, “Don’t tell him how old I am.”

This causes me to wonder if she lies to “her boyfriends at the old-age club,” as she puts it. Perhaps she naughtily tells them that she’s only 85 or so. Strange.

Our meal comes.

She eats her filet mignon like a happy lioness, then focuses back on Eddie. Oh, god! Now she’s trying to organize a conga line. Eddie is shouting at me. “Your mudder,” he yells, “is just my kind of woman, Fatty!”

Darn! I’m losing control. Carolyn is motioning to the bartender: “Tree piña coladas, please!” (We doan pronounce the letter “H” in dese islands.)

I’m a basket case by the time we’re hoisting the Sea Siren over the transom, but she’s having the time of her life. “Feel the breeze!” she cries. “And those flowers—smell those flowers! Isn’t it wonderful to be alive, Timmy?”

Just because she can’t see doesn’t mean she can’t judge. She feels stuff instead of observing it. She feels a halyard I just coiled. “That’s not the way your father used to do it,” she notes.

I explain that we’re using high-tech double-braid now and that this kind of line isn’t coiled quite the same way as three-strand hemp.

Most of her life was spent aboard vessels with kerosene running lights, cotton sails, and tarred manila anchor rodes. She’s agog at our GPS, radar, and watermaker. “Well, I never!” she keeps saying with a shake of her head.

We join a five-boat raft-up for Thanksgiving, and I have to caution her not to eat all the food herself. Later that evening, a dozen of us are singing together in the cockpit, and I hear Carolyn’s voice intertwining with the Sea Siren’s on the same song that we used to sing as a family aboard Elizabeth 55 years ago.

Yes, things change. I’m using LED running lights, Dacron sails, and BBB chain on Ganesh now. But some things stay the same, too. Like the human voice, filled with love.

Cap’n Fatty and Carolyn Goodlander are wrapping up the rebuilding and repowering of Ganesh. Once again, they’ve begun eyeing the western horizon.