Unlike most Maine cruising stories, this one begins in the Pacific Ocean, off the coast of Peru, in early 2010. Aboard the 64-foot cutter Ocean Watch, we were headed north toward the Galapagos Islands — and our ultimate destination of Seattle, where our voyage had originated — on the latest leg of our Around the Americas expedition. By this stage, having negotiated the Northwest Passage and Cape Horn, skipper Mark Schrader, first mate Dave Logan and I had pretty much exhausted most topics of maritime-related conversation; like waterlogged cavemen, we could communicate on nearly any nautical matter, from tying in a reef to heading for the fuel dock, with a wink, nod or shrug. Words were superfluous.

Luckily for us, though, on this stretch of the trip we also had a new crewmember aboard, one with plenty of probing questions about cruising boats, their systems and offshore sailing. Motorsailing up the coast of the blistering flank of South America in an almost windless El Niño year, Billy Gammon was welcome company indeed. Gammon, a native Texan whose wife, Regan, was on the board of the expedition’s primary sponsor, the ocean-conservation group Sailors for the Sea, was using his time aboard Ocean Watch wisely, and with a specific purpose. He was ready to obtain his own long-range cruiser and take her to sea.

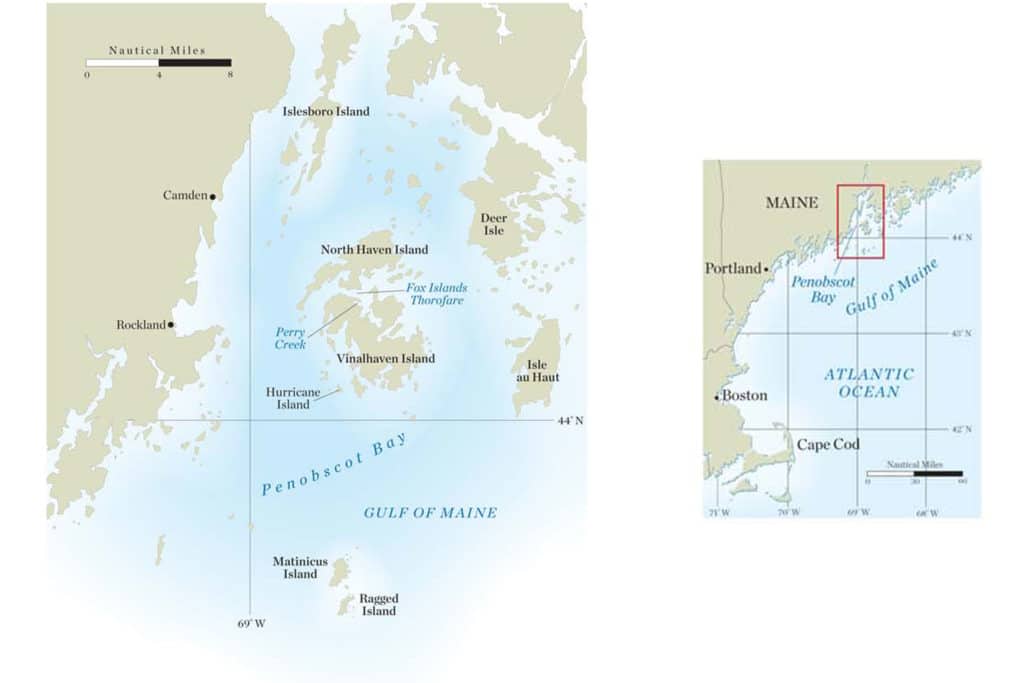

Gammon knew almost exactly where he wanted to go: from his second home on Islesboro, in Maine’s Penobscot Bay, across the Atlantic to the British Isles and beyond. But what he’d get to actually sail there was another thing altogether. He’d done plenty of research and had no end of good ideas, but he was also wide open to suggestions.

In Schrader, Gammon found a passionate advocate of naval architect Bob Perry’s Valiant line of moderate-displacement cruising boats, and why not? Schrader had recorded not one but two solo circumnavigations on Valiants, the first aboard a 40-footer called Resourceful in the early 1980s and the second, in the 1986-87 BOC Challenge, on a 47-foot version named Lone Star. “Mark pretty much sold me on the hull form,” said Gammon, “when he explained how little he knew on that first singlehanded journey and how she got him safely home.”

Logan, who’d worked closely with Schrader on the Resourceful campaign, also vouched for the Valiant. As the de facto engineer on Ocean Watch, who’d helped oversee the boat’s entire overhaul and refit prior to her Around the Americas adventure, Logan also advised Gammon on electronics, rigging, plumbing and just about anything else that came to mind. Logan may be soft-spoken, but he has his opinions. Strong ones. And he was happy to share them.

Fast-forward four years, to 2014. In the years after his stint aboard Ocean Watch, Gammon had pressed forward — with dispatch — on his dream. Almost immediately after our trip, he tracked down a Valiant 42 in Florida that had been built in 1997 and on the used-boat market for a while. A few years languishing in the tropical sun had taken its toll, but she was strong and seaworthy, with good bones. After he purchased the yacht, she was sent north to Maine and eventually to Belfast’s Front Street Boatyard; with Logan consulting on the project, an initial work list was drawn up, one that would grow as the refit proceeded.

Over the next couple of winters — interspersed with some local summer sailing — the 42-footer was completely transformed. Down below, there were new wiring, LED lighting, electronics, an SSB radio, radar and cushions. In came a watermaker and a nifty Dickinson heater. The auxiliary and generator were taken apart and put back together. A new head was added and the plumbing sorted.

Moving on up, the standing and running rigging was replaced, and much of the deck hardware was upgraded. The hatches and port lights were pulled and resealed. Self-steering was addressed: a new autopilot and a Monitor windvane. There was new canvas: a dodger, bimini and cockpit curtains. Bit by bit, the 42-footer was being prepared for, well, anything.

And of course, that also meant a fresh suit of sails. Aboard Ocean Watch, we’d commissioned our old friend Carol Hasse to build us a bulletproof inventory at her Port Townsend Sails loft in Washington State. It was, we reckoned, one of the best decisions we’d made, and Gammon had seconded that opinion during his leg aboard. His revamped cruiser, it was decided, would also fly Hasse sails. In this department, no stone was left unturned, and Hasse’s talented team got to work on a new mainsail, storm trysail, staysail, storm staysail, 110 percent jib and an asymmetric spinnaker. Heck, drawing inspiration from a client who owned a Nor’Sea 27, and knowing Gammon would likely find some breezeless high-pressure zones on the transatlantic trip, Hasse even fashioned a light-air main.

Except for the fine-tuning, and there’d be plenty of that, there was just one major task left to address: a topsides paint job. It turned out to have both aesthetic and personal ramifications. Yes, the light-blue hull proved handsome and striking. What made it special, though, is that while he was at it, Gammon decided to change his boat’s name.

It was a matter he didn’t take lightly. While there was nothing wrong with the boat’s previous handle — Natural Selection — it lacked, he said, “the feminine character that cruising boats favor.”

Prior to his Valiant, Gammon’s formative sailing experiences happened with his mother sailing Down East aboard a modest Pearson 30 coastal cruiser his dad had purchased shortly before he passed away. Together with his mom — and largely because of her forthright initiative — Gammon started sailing in earnest. They learned from their shared mistakes, and had many an adventure in each other’s company — some hilarious, others not, but all in the name of their mutual maritime education and wanderlust. She lived to be 97, and as fate would have it, her days ended at just about the same time her son was pondering a name change for his new yacht.

“In a flash,” Gammon later wrote, the matter was settled. “She would be Eleanor of Hewes Point.” Just like his mother.

Last fall, with one more winter to go before Eleanor would set sail across the Atlantic in the summer of 2015, her crew gathered in Islesboro for a several-day shakedown sail on Penobscot Bay. The plan was to test all the new systems; hoist and trim all the crisp sails; and prepare one final work list to tackle once the boat was hauled and Maine’s snowy season had commenced. Gammon had concluded a four-person crew would be ideal for the crossing, and Logan and Hasse had already signed on to join him. It had been nearly three decades since my first and only transatlantic, an experience I’ve always wanted to replicate. So when he offered me the fourth spot, well, he didn’t have to ask twice.

On the first glorious day of autumn, with clear skies, temperatures in the 60s and a sweet 12- to 14-knot westerly gusting into the upper teens, we pointed Eleanor‘s bow south from Islesboro. And then Hasse’s sail-handling clinic almost immediately began. “Around 18 knots we’ll need to put in the first reef or roll up a little headsail, depending on the angle,” she said. “That’s pretty common on Valiants.” Cruising with Hasse is always instructive.

For a while the sailing was downright stupendous, with Eleanor close-reaching at a pretty consistent 6.7 or 6.8 knots, topping off at 7.4. When the breeze touched 18, as Hasse predicted, the boat was more comfortable after we furled a few turns on the jib. But then the wind softened; the headsail was fully unfurled; up went the staysail. Better. Off North Haven Island, the breeze died further. I was at the wheel when we decided to go up with the drifter.

Uh-oh.

The other headsails had been struck and the spinnaker was aloft in its sock, ready for deployment, when I noticed the water ahead darkening and the shadowy patches closing fast. But before I could say “Hey, it’s about to get kind of windy,” a staunch 25-knot southwesterly was upon us. Since we were on port tack, and the island was directly to port, we couldn’t tack, so the ensuing maneuver — dropping the sock, reefing the main — was a bit of a fire drill. Especially because all the reefing lines and the main halyard were to starboard, which at that very moment was basically an awash leeward rail on a steep heel in the wrong direction.

And of course, because it had been so lovely out, nobody was wearing harnesses. The water in Maine, by the way, is really cold.

Yikes. I could only think: Aren’t you glad you enlisted such an “experienced” crew, Billy? But I decided to keep that one to myself.

We’d had enough fun for the day, so once everything was cleaned up and straightened out, we bore off for Rockland for the evening. On the way over, we deconstructed the day’s events. Yes, we’d already been taught a thing or two, but we all agreed that was the reason we were there in the first place.

The water was darkening but before I could say “Hey, I reckon it’s about to get windy!” the 25-knot southwesterly was upon us.

For Day 2 of our mini-cruise, Gammon wanted to show us one of his favorite little corners of the vast Maine cruising grounds, the snug harbor of Criehaven, on Ragged Island, just south of the larger, better-known island of Matinicus. In a light 10-knot easterly, after breakfast we were again underway.

Back in the day aboard Ocean Watch, by the end of our 13-month journey, we were all well aware of one another’s favorite ways of doing things, to the point that we’d tried to standardize maneuvers and on-deck organization as much as possible. It’s the same deal aboard the better race boats I’ve crewed on. If everyone’s on the same page with stuff like coiling lines and sheets, or running halyards, it becomes second nature — you react instead of thinking about reacting — when things get gnarly or go south quickly and unexpectedly.

Along those very lines, Hasse had clearly given the previous days’ excitement some consideration, and shared her thoughts over second cups of coffee.

A few reefing tips: When tucking in a slab reef, taking in and locking down the boom topping lift a bit is quite useful in easing the loads on the sail, particularly when addressing the reefing line at the cringle, which always seems loaded up. For the main’s new tack, a snap shackle or carabiner is a better, much more secure option than the standard gooseneck hook. Finally, instead of grabbing any handful of sail ties for tying in reefs, she recommended making up and using specific colored ties solely for the main, specifically fitted for that sail. They all sounded like good ideas.

So too was taking a reef in the main as we motorsailed south in spotty air, a practice both Logan and Hasse subscribe to. It makes sense; in that mode, the main is just a steadying sail anyway. With the reef, there’s less sail to trim and, more importantly, less sail area aloft to slat around when pinching, which is often the case when the diesel’s ticking over.

After a while, as the zephyrs persisted, we struck the “main” main entirely and set the replacement light-air mainsail; it’s essentially a triangular drifter with a loose luff. It goes up on the same halyard and is tacked at the gooseneck, just like a real main, sans the track. The only other difference is that the sheet/clew is a dedicated shackle cleated right on the boom, like a reefing line. Because the loads are so light, it’s trimmed right at the cleat, by hand. This was a new one on me, but Hasse’s case for the sail was persuasive; one of the most torturous sounds in sailing is the slat-slat-slat of a traditional main rolling in a swell in no breeze. The nylon replacement eliminates that, and in doing so, also eliminates the shock loads on the rig that occur with a slatting main.

All that said, if I wind up gazing at that sail for extended periods while going nowhere fast during the transatlantic trip, I’m reserving the right to bash my brains out with a winch handle. Not a big fan of drifting under sail.

As the light airs persisted, Logan decided it would be a worthwhile exercise to practice going to windward; he even had a goal. “I’d like to see 35 degrees,” he said, referring to our apparent wind angle. It took a bit of doing, but after experimenting with different sheet leads, we hit the number, making 4.5 to 5.5 knots in about 5-6 knots of true wind…while dragging the dinghy. Cool! We’d already proved Eleanor was a stiff boat. Now we knew she was slippery too.

Criehaven, as advertised, was a cozy but lovely little Maine harbor, chock-full of lobster boats and lobstermen, one of whom told us to pick up his spare mooring, the only free one available. We took advantage of the sensational fall afternoon to work out a permanent preventer for the main boom, and to hoist the storm trysail and determine the ideal sheet placement. Once that was done, Logan said, “May we never have to fly it in earnest.” Amen, brother. At dusk, swarms of mosquitoes threatened to carry us far, far away, so we retired to Eleanor‘s saloon for the evening. It had been another productive day.

Criehaven, as advertised, was a cozy Maine harbor full of lobster boats and lobstermen, one of whom offered us his mooring.

Heading north again the next morning in a pleasant southerly, we finally got a good look at the downwind sails, setting the drifter and, later, poling out both headsails and running up the bay wing-and-wing. Gammon had one last favorite spot to show us, on North Haven Island: a nestled anchorage off the Fox Islands Thorofare called Perry Creek. The cockpit judging panel agreed that the sunset that evening was a solid 10.

We spent our last night aboard enjoying a hot meal and nice wine while watching the “flames” dancing through the window of the new diesel heater. It was pretty terrific. After all, what’s better than hanging out with your pals shooting the breeze in a snug harbor in a warm cabin on a cool autumn night? It was certainly a pleasant way to wrap up a spin through one of America’s most spectacular places to cruise. Will it be as much fun in the British Isles? We aim to find out.

In the meantime, I have one special memory of our shakedown sail. On the stretch from Ragged Island to Perry Creek, having gotten to know Eleanor in so many ways, the last thing I figured we needed to do was have a quick check of the windvane.

I started to say as much to Logan but he shot me a glance I’d seen countless times on the journey around the Americas. It never failed to get across the salient point that whatever I’d just suggested was basically ridiculous; as mentioned, Logan and I don’t require speech to converse. And this time, as always, his silence was clear as a bell. The cocked eyebrow said it all: “Lobster pots. Everywhere. Deploy the windvane? You’re freaking kidding me, right?”

Sometime soon, somewhere between Maine and “the continent” on the other side of the Atlantic, I reckon I’ll be seeing plenty more of Logan’s same loaded looks. Frankly, I can’t wait.

Herb McCormick is CW’s executive editor. This article first appeared as “Shakedown on Penobscot Bay” in the April 2015 issue of Cruising World.

Valiant 42 Eleanor of Hewes Point

Perry Creek off the Fox Islands Thorofare

Dave Logan, Carol Hasse, Billy Gammon

ATN Tacker

light-air main

Spinlock clutches

Maine’s Penobscot Bay

Ragged Island, Maine