The forecast was wrong, but then the forecast was always wrong during the South African summer of 2016-17, so I left anyway.

I had watched the weather for two weeks while antifouling and provisioning my ultralight Moore 24, Gannet, and then for another week after I was ready to sail, without ever seeing what I wanted.

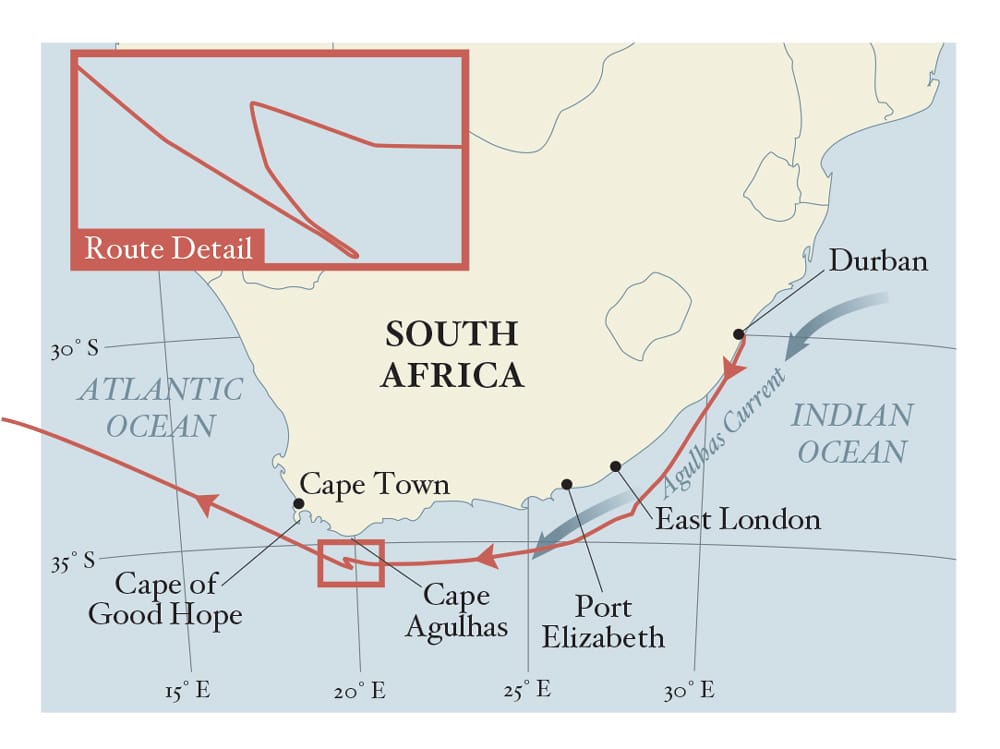

This was my fourth time in South Africa, my third sailing west from Durban. On previous voyages, I had been able to wait for a high to drift over the region, providing three or four days of light east wind, which with a boost from the Agulhas Current, easily enabled me to cover the 400 miles to Port Elizabeth in three days before the wind changed. But that summer, the wind never remained east for even 48 hours.

By February 9, I was tired of waiting. The seven- and 10-day GRIBs I downloaded with LuckGrib showed the continued pattern: east wind for Friday and Saturday, followed by 30 knots from the west for 12 hours on Sunday; east again for a day or two, followed by west at 25 to 30.

Once I go to sea, I don’t worry about the weather. I expect that I can deal with whatever happens as I always have, and my “always” is longer than most. I don’t seek outside weather information. I look at the sky, at the sea and at the barometer. So I decided to turn a coastal passage into an ocean voyage. Instead of trying to duck in and out of harbors — and there are none for the 240 miles from Durban to East London — I would go to sea and stay there, easing Gannet offshore beyond the strongest of the Agulhas Current and hopefully most shipping; sail hard when the wind was behind me; and lie ahull when it was from the west. As far as I know, Gannet was the smallest boat to clear into Durban that year. She certainly was the only one of any size to clear out for St. Helena. The immigration official asked where that was. Sorry, Napoleon.

A local friend, Chris Sutton, came down to see me off. At 0730, a breath of wind came from the southwest. Chris took the dock lines and walked Gannet out of her slip. When I put the electric Torqeedo outboard in gear, Chris called that its quiet whirring sounded like something from Star Trek and that she was Starship Gannet.

The Torqeedo’s battery is old and has limited range. I was not confident it would last the 2 miles from Durban Marina to the outer end of the channel breakwaters, so as soon as we were clear of the moored boats, I raised sail and alternately glided and powered at 3 knots across the busy harbor. Ahead of us, two tugs were pulling a ship sideways from its berth, while to port, a slab-sided car carrier had just tied up.

As the last hour of ebbing tide carried us to the end of the entrance channel, we cut across the wake of a pilot boat. When the bobbing ended, I leaned over the transom and removed the Torqeedo and outboard bracket. They wouldn’t be used again for thousands of miles. I turned Gannet southwest. In the next few days, the boat would round 700-mile-distant Cape Agulhas three times, have its longest day’s run ever and its shortest. The longest came first.

Gannet slashed through the night: pale water everywhere; surging bow wave; foaming wake; cresting 6-foot waves; sounds of rushing water and wind. Despite being heavily laden with provisions for more than two months, the boat had constant, quick motion. It slid down some waves, surfed evenly for several seconds on others. Gannet has no tendency to broach. It surfs straight, and the Pelagic tiller pilot was steering well.

Several hours earlier, I had lowered the mainsail and set up a running backstay. An hour after that, I furled the jib to half size. Even under such a small amount of sail, with 25 knots of wind behind her, Gannet was sailing at 8 to 10 knots, more when she caught a wave, and with the boost from the Agulhas Current, we were seeing speed-over-the-ground between 10 and 13 knots. Light rain and a falling barometer heralded the approaching front.

When at 0100 the wind began to push Gannet‘s stern around, I altered course to head farther offshore. Reportedly, the Agulhas Current is strongest on the 200-meter curve, roughly 660 feet deep, and I didn’t want to be on it still when the wind headed us and blew against the current. The coast from Durban to Port Elizabeth trends southwest. From Port Elizabeth to Cape Agulhas, the southern tip of Africa, west. At sunset that first evening, we were 6 miles offshore, and by the following dawn, more than 30 miles.

I don’t usually sleep well the first night back at sea, and I was up often that night, looking for ships, of which I saw surprisingly few, and making sure Gannet was balanced and under control. The next morning, I dozed off repeatedly at “Central,” as my place sitting on a Sport-a-Seat facing aft on the great cabin floorboards is known.

The wind decreased to 20 knots and the waves to 6 or 7 feet. Some of them slammed into us with a percussive sound that in Gannet makes me feel as though I am inside a drum. By noon, the barometer had dropped 10 millibars in 24 hours, and we were 43 miles offshore.

I put a waypoint into the iNavX chart plotting app on my iPhone each noon and measure daily runs back to it. With any change in course, Gannet sails farther than this straight-line distance, but I have always preferred understatement to hyperbole. That day, the noon-to-noon distance was 180 miles, Gannet‘s best ever. Because the wind had been light the previous afternoon, I was certain that a 24-hour run from 1800 to 1800 would be even greater, perhaps approaching 200 miles, but I had no way to measure that.

Enough water was coming on deck that I had to put on my foul-weather gear any time I poked my head out. I stood in the companionway briefly, not wanting a wave to flood below, and looked around. A sunny, mostly blue sky. This was great, exhilarating sailing. I wished it would last, but I knew it wouldn’t. Tomorrow, stronger wind would head us. I was not looking forward to it.

The wind began to back at sunset, and at midnight I decided to lie ahull while it was still relatively easy to move about on deck. I put on my foul-weather gear and furled the jib, lowered the main, disengaged the Pelagic tiller pilot, tied the tiller amidships and took the tiller pilot below. All this was a little premature, but I slept better, and by dawn, the wind was gusting the predicted 30 knots and heeling Gannet 15 degrees just from pressure on her mast and hull.

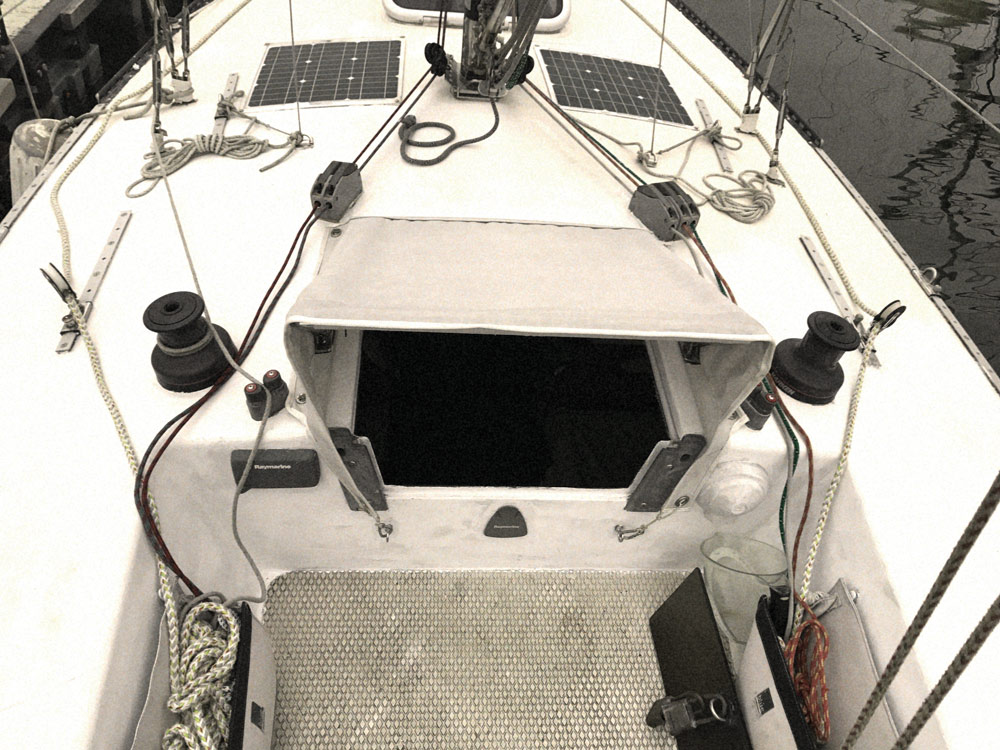

With wind against current, I expected the waves to build, but they remained only 6 to 7 feet, though some broke over us. Inspired by a Danish reader of my online journal who sent me photos of a small spray hood that quickly folds down on his small sloop, I had one made for Gannet in Durban. I can raise and lower it from inside the cabin, and now it was up, proving itself by preventing most of the water washing the deck from coming below.

My now two-day-old forecast proved to be precisely right. It showed southwest wind lasting 12 hours. I hove to for 13. The wind continued to back, and by 1300, it was no longer heading us and had decreased to just under 20 knots. I unfurled part of the jib and the little sloop began to sail at 4 to 5 knots. By 1630, I had let out more jib and Gannet was making 7.

Monday, our third day at sea, found us 25 miles south of Port Elizabeth. Even lying ahull for 13 hours, we could have reached the harbor in three days, but I was glad we had not tried. It would have been a tense dash to get in before the wind shift.

Cape Agulhas was now 282 miles ahead, almost due west. I began to hope we might make it around before the next front brought head winds, but those hopes vanished with the breeze. In good visibility I could see land and more ships than I wanted to, some even passing outside us, but none worryingly close. The tiller pilot kept our bow pointed west, and the Agulhas carried us that way at a knot or 2 with little assistance from limp sails.

After one slow day, the wind returned, and we still almost made it. In fact, we did make it. For a while.

Sunset of our seventh night at sea found us 11 miles east and 35 miles south of Cape Agulhas, almost on the same latitude as Opua, New Zealand, and, as I thought incorrectly, the farthest south we would go on this circumnavigation, with decreasing and ominously backing wind. The gray sea, jagged earlier in the day, smoothed. I stood in the companionway and looked around for ships. I didn’t see any, but they were certainly there somewhere. Knowing I would be up often that night, I closed the companionway and went to sleep.

Sleeping was difficult. I sleep on whichever is the windward pipe berth, behind a lee cloth and with flotation cushions wedged between my knees and back and the hull, and a hard edge of wood around the companionway. The Avon Redstart and two waterproof food bags live on the lee berth, and when the backing wind compelled me to jibe Gannet to port, I had also to jibe the dinghy and bags and my sleeping bag and pillow.

At midnight, my iPhone showed the bearing to a waypoint at Cape Agulhas to be 10 degrees. We were in the Atlantic, but as the ancients knew, there is but one ocean, and our modern divisions are arbitrary. We had a straight course to the Cape of Good Hope, but Gannet sped through the night only for three more hours. By 0330, the wind was blowing 30 knots directly from Good Hope. With reduced sail, Gannet can beat to windward in such conditions, and I have, but it is miserable to do so. None of my boats, with the exception of Chidiock Tichborne, whose mizzen weather-cocked its bow into the wind, have hove to well, so I went on deck and again set Gannet up to lie ahull.

In an interview a few months earlier, I had been asked what I am still learning. It is a good question to which I did not have a good answer. Now I realized that perhaps what I am still learning is when not to suffer needlessly. There are times when you have to push yourself and your boat hard, but there are times when you don’t.

I looked around and saw the running lights of two ships miles north of us. The wind was shrieking in the rigging. A wave crashed over the bow and flooded aft. I quickly stepped below and pulled up the spray hood, which must be lowered every time I go through the companionway. Then I shut the hatch.

Dawn found us still in the Atlantic. By afternoon, we weren’t. The barometer was rising as quickly as it had fallen the previous day. Without sail up, Gannet is a cork, and while her motion was wild, we were not in any danger, except from shipping, and we were beyond most of that. I wedged myself in at Central, read and watched on the iPhone as Gannet was pushed back southeast.

In midafternoon, the wind began to decrease. At 1620, the bearing to Cape Agulhas was 0 degrees, and we returned to the Indian Ocean.

Two hours later, the wind abruptly dropped to 11 knots and backed southwest. Under main and partially furled jib, Gannet again sailed toward the Atlantic, but the wind soon died away completely and we didn’t make it that night.

The following noon found us sailing at 5.5 knots, back in the Atlantic, Cape Agulhas passed for the third — two west, one east — and, I hoped, last time, and a noon-to-noon daily run of 13 miles. Gannet‘s tortuous course had covered considerably more distance during those 24 hours, but, as I measure, it was by far its slowest day’s run ever.

The sky cleared and the afternoon became pleasant. When the wind continued to back and lighten, I set the North G2 asymmetrical and sat on deck, enjoying Gannet sailing at wind speed. For 8,000 miles, ever since rounding Australia’s Cape York, our course had been west. Now it was north.

Two dawns later, I watched the sun rise behind the Cape of Good Hope, which Sir Francis Drake called “a most stately thing and the fairest cape we saw in the whole circumference of the earth.” It was a beautiful sight, the cape peninsula dark gray, almost black, against an orange-and-rose sky.

As we continued north, we startled several seals sleeping with one fin out of the water 20 miles offshore. They were fortunate Gannet is an innocent bird and not a great white shark, which also frequents those waters.

Table Mountain and Cape Town, which has one of the most beautiful natural settings of any city in the world, came into view. On two voyages I’ve happily stopped there. But this was an ocean passage, and I was glad finally to leave the land behind. I turned Gannet out to sea.

Webb Chiles, 76, a five-time circumnavigator, will return to *Gannet at Hilton Head Island, South Carolina, in late August, and if the weather cooperates, sail the Moore 24 ultralight to the Chesapeake in early September. He will speak at the Chesapeake Maritime Museum’s Small Boat Festival on October 6. In January 2019, he will sail for San Diego via Panama to complete the Gannet voyage and his sixth great circle. *