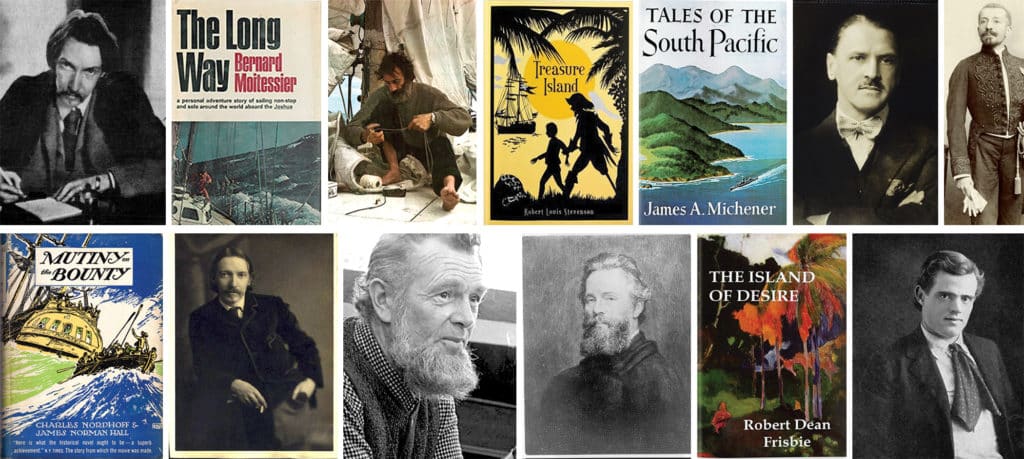

The South Indian Ocean and the South Atlantic Ocean. For most sailors and nonsailors, these two place names conjure nothing more than spots that can be pointed to on a globe. But one mention of the South Pacific, and even a farmer in Nebraska who’s spent his entire life in the American Midwest will conjure a ready knowledge of white-sand beaches, topless native women and cannibals. The farmer might even mention the Southern Cross, Tahiti and tattoos, or Polynesia, grass skirts and whale-bone carvings. South Pacific lore was born over a century ago, about the time that men began leaving ports by choice to sail very small boats across oceans. Upon returning, a few of them, with thick fingers calloused by salt and rope, began writing. For hundreds of pages, they shined a soft and enticing light on the most remote and inaccessible landscape on Earth. They wrote of being carried along by warm trade winds and of landing in exotic, tropical places. Their works inspired other writers (as well as artists and philosophers) to follow in their wakes — and more was written. Ultimately, a collection of writers and their stories offered Western culture the first romantic notions that still draw cruising sailors to the South Pacific today. Some of these writers you are likely familiar with; others I hope to introduce you to. Most interesting to me are the connections that existed between several of them. May learning about these authors fuel your own desire to set sail for the island places they loved and described.

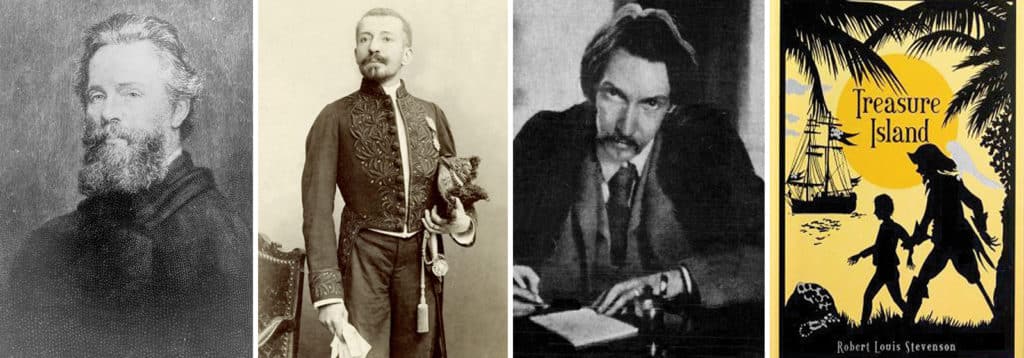

HERMAN MELVILLE

(1819-1891), United States

Herman Melville worked as a school teacher outside Lenox, Massachusetts, when he took a crew position on a merchant ship at age 20. He briefly returned to teaching, but then, perhaps inspired by Richard Henry Dana Jr.’s Two Years Before the Mast, Melville signed on to work aboard the 104-foot three-masted whaling ship Acushnet, sailing out of Connecticut.

After rounding Cape Horn, and more than a year after leaving the United States, Melville jumped ship on the island of Nuku Hiva, in the Marquesas, initially hiding in the mountains to avoid capture by his shipmates. After weeks ashore, Melville boarded Lucy Ann, took part in a failed mutiny and was jailed in Tahiti. He escaped after a couple of months and lived on nearby Moorea before signing on to the whaler Charles & Henry for a six-month voyage to Hawaii. There he joined the Navy and served aboard the frigate USS United States, which set sail for Boston. Ten days after the ship arrived in October 1844, Melville was discharged and began writing.

His first, and best-selling work in his lifetime, was Typee: A Peep at Polynesian Life (1846). Typee is a romanticized, exaggerated account of Melville’s time spent living among the Polynesians in the Marquesas. Historians have suggested that authors Jack London and Robert Louis Stevenson were informed and inspired by Typee.

Melville followed up with a sequel and wrote additional books and stories, including Moby-Dick, a commercial failure that put his writing career in the dumps. Following the publication of Moby-Dick, Melville began working as a customs inspector in New York, writing poetry in his spare time. One of his sons committed suicide, a second died, and Melville eventually succumbed to heart disease in 1891.

PIERRE LOTI

(1850-1923), France

In 1872, 22-year-old Pierre Loti lived in Papeete, Tahiti, for a two-month period that he characterized as “the dream of my childhood.” While there, he immersed himself in Tahitian culture: learning the language, living among the people and loving many women. In 1880, he found a publisher for his autobiographical work of fiction, The Marriage of Loti. At the center of the story is Loti’s romantic liaison with an exotic Tahitian girl.

The Marriage of Loti was a huge success (even turned into an opera called Lakmé) and influenced Paul Gauguin to travel to the South Pacific, where he lived and painted extensively before his death in the Marquesas. Contemporary literary critic Sir Edmund William Gosse said, “At his best, Pierre Loti was unquestionably the finest descriptive writer of the day.”

ROBERT LOUIS STEVENSON

(1850-1894), Scotland

One day in the early 1880s, in rainy Scotland, his head filled with adventurous tales of other writers, Robert Louis Stevenson and his stepson passed the time drawing an elaborate map of an imaginary island. Soon afterward, he conceived the plot of Treasure Island, published in 1883.

Though it’s widely acknowledged that Stevenson was consciously influenced by similar works by other writers, it’s from Treasure Island that our culture can attribute references such as treasure maps with an X marking the spot, and the seaman with a missing leg and a parrot on his shoulder.

In June 1888, in search of a climate that would be more conducive to his failing health, Stevenson chartered the 90-foot schooner Casco and set sail with his family from San Francisco to Hawaii. From there, they continued to the South Pacific, where he bought 400 acres in Samoa.

He became very active in local politics as a defender of the Samoans against colonial administrators. He took the name Tusitala, Samoan for “teller of tales.” In December 1894, at age 44, Stevenson looked up at his wife and asked, “Does my face look strange?” before dying of what is thought to have been a cerebral hemorrhage.

Two years after his death, In the South Seas was published. It’s part autobiography, part anthropology, and chronicles his travels with his wife, Fanny, and their family in the Marquesas and Tuamotus from 1888 to 1889. Today Stevenson’s home and gravesite in Vailima are a tourist draw, but also a place revered by Samoans.

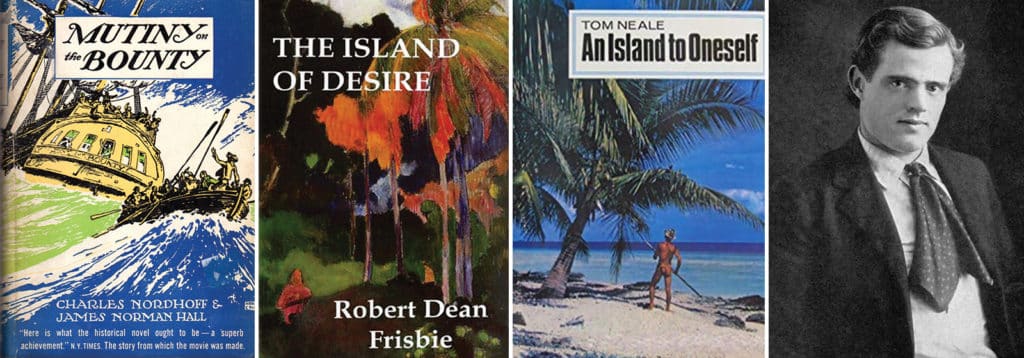

JAMES NORMAN HALL

(1887-1951), United States

CHARLES BERNARD NORDHOFF

(1887-1947), United States

Charles Bernard Nordhoff and James Norman Hall were Americans who both served as pilots in the Army in Europe during World War I. But it was not until after the war that they met, when commissioned to together write a history of their Army unit. The collaboration was successful, and when Harper’s magazine commissioned the pair to write travel articles about the South Pacific, they both moved to Tahiti.

When the Harper’s assignment was completed, they continued living in Tahiti, working on assignment for The Atlantic during the 1920s and 1930s. Both Nordhoff and Hall married Polynesian women and raised families. At the same time, Hall suggested they collaborate on a trilogy: Mutiny on the Bounty, Men Against the Sea and Pitcairn’s Island.

Their partnership is one of the most successful in literary history and spans many more novels, including The Hurricane, a romantic tale of Polynesian life in the South Pacific that was later adapted to film by director John Ford.

ROBERT DEAN FRISBIE

(1896-1948), United States

Influenced by Robert Louis Stevenson, and spurred by his doctor, who advised him to seek a warmer climate, Robert Dean Frisbie moved to Tahiti in his 20s. Shortly after arriving, he met Charles Nordhoff and James Norman Hall, who both encouraged him to write.

In a search for solitude, Frisbie moved to the Cook Island of Pukapuka, where he met his Polynesian wife, Ngatokorua. Despite seeking peace and quiet (the pursuit of which was a theme throughout his writings), the couple had five children before the family relocated to Tahiti in the 1930s. Less than a decade later, Frisbie’s wife passed away and he and his five children relocated to uninhabited Suwarrow Island. They lived on the shallow atoll for a full year on their own, surviving a direct hit by a cyclone. The story of their survival was serialized in The Atlantic and was the subject of his third book, The Island of Desire.

In 1943, Frisbie was diagnosed with tuberculosis and evacuated from the Cook Islands to a hospital in American Samoa by a young Navy lieutenant, James Michener. Frisbie recovered, only to die in the Cook Islands a few years later, of tetanus. In all, Frisbie wrote 33 magazine stories and six books, including My Tahiti.

TOM NEALE

(1902-1977), New Zealand

Tom Neale was a New Zealander who traveled the Pacific islands for decades as a young man, first in the navy and then aboard any boat or ship that would have him. He eventually settled in Tahiti, where he lived until 1943, when the urge to explore hit again. In the Cook Islands in 1948, Neale met Robert Dean Frisbie, who regaled him with tales of his time spent on Suwarrow Island. Inspired, and likewise in search of solitude, Neale landed on Suwarrow in 1952 with only the supplies he could scrape together.

In three separate stints, punctuated by illness, marriage and government edicts, Neale spent 16 years on Suwarrow. Out of this experience came the classic An Island to Oneself. In this memoir, Neale recounts long months in blissful isolation, extreme physical and emotional hardship, and a parade of intermittent visitors, including a cruising family in the early 1960s who stopped by only to lose their yacht on a reef during an overnight squall. The couple and their daughter ended up living with Neale for months before they were able to signal a passing ship.

JACK LONDON

(1876-1916)

Jack London was one of the first fiction writers to obtain worldwide celebrity and a large fortune from fiction writing alone. Though he is known mostly for his stories unrelated to the nautical life, he wrote 10 books on the Pacific, set in places such as the Marquesas and Solomon Islands. Tales of the Pacific is a collection of stories that some consider London’s best writing.

London and his second wife, Charmian, were sailors and Pacific cruisers. In 1906, he commissioned a 45-foot ketch, Snark, for a planned circumnavigation. In April 1907, he and his wife and small crew set sail out of San Francisco. London taught himself celestial navigation and seamanship underway, and visited Hawaii, French Polynesia, Samoa, Fiji, the Solomon Islands and Australia.

London was inspired by Herman Melville’s Typee and was dismayed to find what he described as “a dismal swamp” when he visited the setting of that book, Taipivai in the Marquesas.

W. SOMERSET MAUGHAM

(1874-1965), U.K.

Writer W. Somerset Maugham was not a sailor, but was drawn to the South Pacific by his interest in one of the Marquesas’ most famous (and infamous) residents: artist Paul Gauguin. His time in the Pacific yielded not only his book on Gauguin (The Moon and Sixpence) and A Writer’s Notebook, chronicling his island travels, but a remarkable short story titled Rain.

In December 1916, traveling via the steamer Sonoma, Maugham got held up in Pago Pago, American Samoa, for a quarantine inspection. Delayed for several days of torrential rain, he and the other few passengers holed up in a lodging house. These other passengers inspired the characters of Maugham’s contemporary morality play.

Rain is the story of Miss Sadie Thompson, a smoking, drinking, jazz-loving young prostitute arriving in Pago Pago to begin work for a shipping line. But her paths cross with a smitten military sergeant who wants to help her jump-start a new life in Australia, and a zealous missionary couple who want her to return to the States and repent for her sins. The short story is lush in its South Pacific setting and was immensely influential. Sadie was three times depicted on the silver screen by the likes of Gloria Swanson, Rita Hayworth and Joan Crawford.

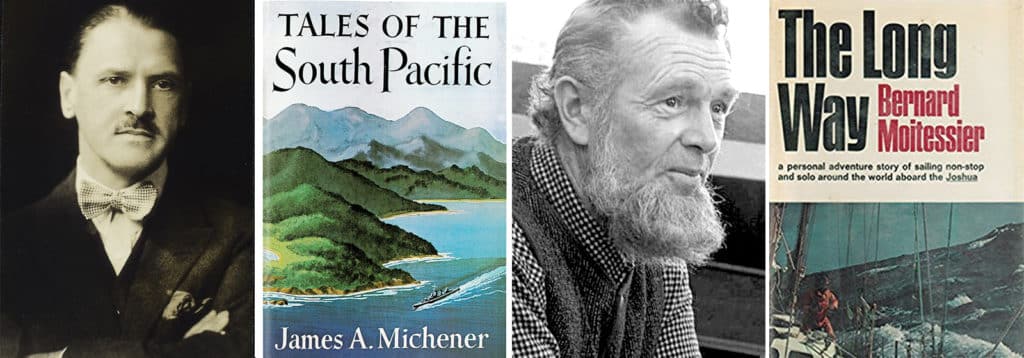

JAMES A. MICHENER

(1907-1997), United States

Raised a Quaker in rural Pennsylvania, James Michener was the beneficiary of circumstance when drafted into the service in the Pacific theater during World War II. Somehow, his base commander mistakenly assumed he was the son of Adm. Marc Mitscher, whose name was only similar. Of course, this resulted in plum assignments for Michener, who eventually worked during the war as a naval historian.

But it’s also lucky for us because the time Michener spent in the Pacific left an impression, and after the war Michener wrote Tales of the South Pacific, for which he won the 1948 Pulitzer Prize for Fiction, along with extraordinary commercial success. In Return to Paradise, Michener wrote, “The great writers, Conrad, Maugham and Melville, spent only a few years in the South Seas, but their memory of those waters was indestructible; for the nature of life in the islands commands attention to the vivid world and its even more vivid inhabitants.” The same could be said of Michener himself.

STERLING HAYDEN

(1916-1986), United States

Like Robert Dean Frisbie and Tom Neale before him, Sterling Hayden sailed to the South Pacific in a bid to escape the trappings of Western life. He’d come of age as a deckhand on schooners, reached the ranks of mate and then skipper as a young man, and had sailed around the world several times before being discovered by Hollywood, first as a model and then as a leading man. As his lights-camera-action career took off, Hayden acquired wealth and fame at the cost of a life he found complicated and litigious. He grew unhappy, and when a divorce judge forbade him to take his kids sailing across an ocean, he did just that, firing up the tabloids and ending his career. His 1962 memoir, Wanderer, captures Hayden’s inner philosophical monologue around this turbulent time and has since been adopted by cruising sailors as a manifesto of the motivations that underlie their passion to cast off.

In 1976, having returned to Hollywood with a role in The Godfather, Hayden followed up on the success of Wanderer with a novel, Voyage.

BERNARD MOITESSIER

(1925-1994), France

Up until his 40s, Bernard Moitessier was an experienced, well-known and well-regarded sailor among the French sailing community. Famously, in 1965, in a hurry to get back to France from Tahiti before their kids were discharged from boarding school, Moitessier and his wife, Francoise, sailed their 39-foot steel ketch, Joshua, direct and eastbound, more than 14,000 nautical miles in 126 days. At the time, it was the longest nonstop passage ever conducted on a yacht.

Moitessier’s most notable story is a twist of Sterling Hayden’s before him. On the verge of possibly winning the 1968 Sunday Times Golden Globe Race (the first race of solo, unassisted, nonstop circumnavigators), for which he stood to gain enormous fame and a sizable purse, Moitessier changed course and continued on, turning his back on the prize. “Because I am happy at sea and perhaps to save my soul,” is the oft-quoted translation of the Frenchman’s reasoning. He continued sailing two-thirds of the way around the world again, returning to French Polynesia’s Tahiti.

His book, The Long Way, is a memoir of the experience and a modern classic of sailing literature. Additionally, Moitessier wrote several other nonfiction sailing books that have been translated to English. Moitessier’s passions were tied to the South Pacific, and this is evident in his writing. During his life, he spent much of his influence protesting the testing of nuclear weapons in the area and the overdevelopment of French Polynesia in particular.

Michael Robertson is cruising with his family aboard Del Viento, a 1978 Fuji 40. He is the editor of Good Old Boat magazine, author of Selling Your Writing to the Boating Magazines and co-author of Voyaging with Kids.

South Pacific Writers: Then and Now

A list of writers such as this cannot exist as a discrete entity. There are too many questions raised that must be addressed, if not answered. I’ll try and cover the most glaring.

Notably, my list is of non-Pacific Islanders writing about the Pacific Islands. This is because, prior to the formation of the University of the South Pacific in Suva, Fiji, in 1967, storytelling among South Pacific island cultures was largely oral. Today, perhaps the most widely known Pacific Island novelist is Samoan Albert Wendt. He is the author of more than two dozen novels and collections of stories and poems, and is a professor of English at the University of Auckland.

My list also stops short of including contemporary writers, Western or indigenous, such as Lloyd Jones, Thor Heyerdahl and Paul Theroux. My aim was to restrict the scope of this story to those authors who laid the foundation for the mythology of the South Pacific geography and culture, the primary elements, absent the complexities that more recent writers appropriately bring to light.

Finally, I ignored the critical role of philosophers in shifting the Western mindset toward acceptance of a tropical paradise. It’s difficult to imagine now, but prior to the idea of the “noble savage,” people “untamed” by civilization were assumed to be barbaric and were feared. But as the idea of the “noble savage” gained currency in the 1700s, explorers’ accounts of warm receptions by remote Pacific Islanders made sense to the collective consciousness and made it possible for novelists to lure readers with descriptions of an otherworldly paradise over the horizon.