After departing remote and beautiful Penrhyn Atoll in the Northern Cook Islands, my fiancée, Gayle Suhich, and I made for Suwarrow Atoll, 450 miles to the southwest. A moderately fresh breeze to start our passage aboard Small World II, our Flying Dutchman 50, ended up petering out on us after the second day. At one point on what became a very slow passage, when our ¾-ounce spinnaker finally collapsed like a deflated balloon, we simply took down all the sails and went to bed — only losing 1.8 miles overnight. Just after dawn on Day Five, while motorsailing in a light easterly, we picked up the line of palm trees on Suwarrow Atoll, and by 1000 we entered the wide, easy-to-navigate pass and made our way into the lee of the main islet. Two boats were at anchor there when we arrived, and shortly after us, a third yacht came in. Compared to where we had been traveling for the last few months, this was a real crowd! (See “A Pearl of the Pacific,” June 2015.)

No sooner had we put our hook down than 22 small- to medium-size blacktip reef sharks came swarming around our boat. We’d caught a tuna just prior to coming in the pass, so there was likely still some blood in the scuppers attracting undue attention. The water clarity was outstanding, and we could easily see our anchor on the bottom in 50 feet of water. Carefully placing the anchor so we didn’t damage any coral, we saw that buoying our chain might be necessary to keep it clear of the numerous coral heads in the anchorage, should the wind veer at all.

Suwarrow is a Cook Islands National Park, and so we’d expected to see park rangers ashore. Yet after a brief conversation with the skippers of the two other boats that were there when we arrived, we discovered that the island caretakers were not yet there for the season, and that the island is uninhabited for six to seven months of each year.

Going ashore, we found overgrown pathways choked with leaves and debris from past storms. We made our way up the main trail from the old broken-down stone wharf, and came upon a building that had been constructed during World War II by the Australian military. The structure had housed coast watchers during that period. It and the substantial water catchments were still usable, for the most part, and a newer two-story building of sturdy pole construction was set to the south. This larger structure housed the quarters for the caretakers, and had a large open-air area in the lower level that was identified by a large wooden plaque as “The Suwarrow Yacht Club.” Flags from many yachts were secured to the rafters and beams of the place, and it was interesting to see a Seven Seas Cruising Association burgee from the vessel Caribee, a boat owned by our cruising friends Randy and Cheryl Baker, a couple we knew from our earlier cruising days back in the 1980s. Small world.

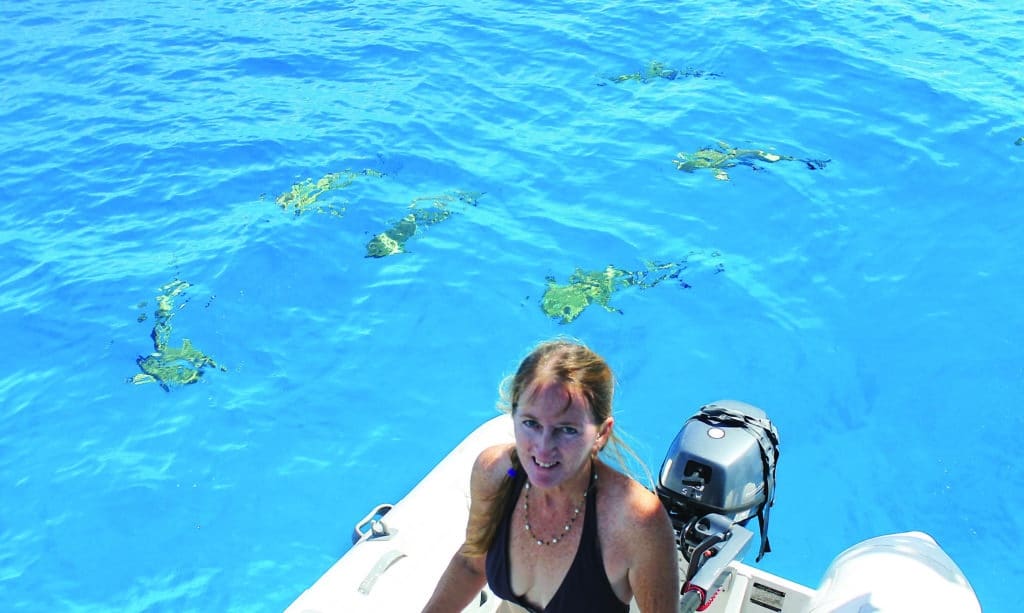

Over the coming days we spent substantial amounts of time exploring the main island, called Anchorage Island, and took our dinghy near some of the other tiny adjacent motus, taking special care not to get too close, as these islets are important breeding sanctuaries for numerous species of seabirds.

We also snorkeled some of the many reefs both close by and across the large lagoon. Fine weather allowed us easy access far and wide. While snorkeling in the pass, Gayle saw manta rays, giant grouper and many larger grey reef sharks.

We took one trip by dinghy near an island that had extensive seabird colonies, and were able to see thousands of chicks milling about in the bushes, in addition to the hundreds of seabirds flying to and from the colonies. Most spectacular to see were the great and lesser frigate birds, whose main breeding colonies are on Suwarrow’s small motus. Watching them as they wheeled overhead in the hundreds was a sight to remember.

One evening, we joined the crews of the other boats and held a potluck ashore at the Suwarrow Yacht Club. On another day, we had a second potluck in an old hut near the water. We later learned that this was Tom Neale’s “summer house” — an open-sided palm-frond and stick shelter, which is still in evidence likely due to regular reconstructions performed by the crews of various cruising yachts over the years.

Tom Neale, of course, was the island’s most well-known resident. Over three extended periods from 1952 to 1971, the Kiwi lived the hermit’s life here. At one point he went 14 months without a visitor, and his book, An Island to Oneself, written at the end of his second stay on the island, is a South Seas classic and a must-read for anyone planning to come this way. Standing on the shoreline looking to the west as the sun set across the wind-swept lagoon, I tried to imagine what it must have been like to be so alone, on an island barely 6 feet above sea level, with no radio, no electricity and only your own ingenuity to keep yourself alive.

The anchorage behind what is identified in most literature as Anchorage Island, or occasionally Home Island, is tenuous at best and safe only in settled weather. While we were there, the winds came up and blew quite strongly out of the south-southeast for three days. This made the 5-mile fetch across the lagoon quite bumpy, as there is virtually no protection from Anchorage Island in a southerly wind. We had upped anchor after the first night and managed to tuck in closer to the northwest shore in a small pocket in the reef that had room for about two boats. A Pearson 36 with two young men arrived a few days later, and at our suggestion they took advantage of this spot and anchored close to us. The other boats farther out made the best of it, bucking as the winds howled in the rigging and the 4-foot waves challenged the snubber lines. A few days later the winds lay back down and went more easterly, and we were able to relax and continue our exploration of the lagoon by dinghy. Suwarrow’s reputation for having a somewhat dangerous anchorage is well-earned. We heard by radio later in the season that a large Amel had a ground tackle failure in bad weather one night while anchored in the lagoon. We were told that the vessel went up on the reef while trying to make a nighttime escape, resulting in a total loss. Thankfully the people survived.

Near the end of our second week at Suwarrow, a ship arrived from Rarotonga. Lady Moana anchored in the lagoon with the island’s caretaker and his wife aboard. Within a few hours this couple and all their supplies for the next six months were landed at the battered old stone wharf. The ship departed before sunset, a rainbow framing it as it made its way out the wind-swept pass, bound for Manihiki.

Going ashore the next day, we were pleased to meet Harry Papai and his wife, Vaine. Harry is a New Zealand-educated, well-spoken Cook Islander, originally from Manihiki. The couple were in the middle of a three-year contract to oversee the safekeeping of Suwarrow’s fantastic natural beauty. They also carry out scientific research for a number of organizations and, of course, are there to welcome yachts when they arrive. A nominal fee of $50 to visit the atoll is charged, but we felt that this was insignificant when considering that yachts are the only visitors to this remote place. Depending on the year, there might be as few as 50 boats coming through, or as many as several hundred if the winds to the south are strong enough to cause sailors to take this typically less-traveled, northern route to the west.

Several days of calm conditions allowed us to explore some of the reefs that dot the otherwise deep lagoon at Suwarrow. With names like Baby Patch, Man in the Boat and Perfect Reef, each major formation offered unparalleled snorkeling with myriad species of coral, huge mantas, spotted eagle rays, giant grouper and many species of shark. These reefs are as unspoiled as one could hope for, and the sheer magnitude of the sea life all around us was astounding. Spearfishing inside the lagoon is not allowed, and the presence of so many inquisitive and sometimes brazen sharks in any case would have quelled our enthusiasm for bringing a fish up and to the dinghy. However, trolling by dinghy along the pass, several yachts’ crews were able to catch grouper, rainbow runners, jacks and tuna fairly easily.

After two weeks at this pristine tropical paradise, we were finally compelled to get moving toward American Samoa, where Gayle’s daughter was due to arrive. We managed to take a night’s break along the relatively short 400-mile downwind run to Pago Pago with an overnight stop at Tau, in the Manu’a Islands. Located just 60 miles to the east of Tutuila, which is the main island in the American Samoan territory, the Manu’as consist of two sparsely inhabited and starkly beautiful high islands on which large sections have been set aside as part of the National Park of American Samoa. Because we’d not yet cleared into American Samoa, regulations did not allow us to go ashore at Tau. We did, however, enjoy the relatively sheltered roadstead anchorage on the northwestern corner of the island, beneath the shadow of 3,000-foot-high Lata Mountain. Unfortunately, strong easterlies and limited time prevented us from returning to explore these islands more thoroughly. We learned that a ferry does make the run from Tutuila to the Manu’a islands several times a week, so visiting could be relatively easy while leaving your boat safely anchored in the all-weather harbor of Pago Pago.

Arriving finally in Pago Pago (pronounced “Pango Pango”), American Samoa, just prior to the Fourth of July, we once again entered civilization, with Internet, shopping and many other cruising yachts. Three weeks whisked by as we went sightseeing and visited friends ashore. Gayle’s daughter, Sarah, also arrived to accompany us for a couple of months. Provisioning and minor repairs kept us occupied as we prepared for the next phase of our voyage across the Pacific and for our planned stop at the very remote islands of the Niua Group, in northernmost Tonga.

Todd Duff and Gayle Suhich have been cruising and living aboard various sailboats since the 1980s. Both are accomplished sailors and licensed captains. Todd has worked as a yacht broker and is an accredited marine surveyor. Gayle has worked in the crewed charter industry for most of her life. In between work obligations, they sail far and wide at every opportunity.