It’s a multi-part question that’s near and dear to the heart and soul of every sailor, including dedicated cruisers with no desire to test themselves on a racecourse: What’s my optimal sail inventory, what are my choices in construction and materials, and what do I need to know about trimming, or shaping my sails to maximize their performance?

The pros at Quantum Sails, including sails consultant Andrew Waters and technical consultant Joan Subirats, have given these issues considerable thought and reflection. In wide-ranging interviews with this pair of vastly experienced yachtsmen and sailmakers about optimizing sail shapes for cruisers, the conversation veered into the differences in cost and effectiveness between Dacron and carbon fiber, the pros and cons of cross-cut versus tri-radial construction, and why the notion of “sail-shape retention” is so important.

Perhaps surprisingly, however, despite the rather technical slant of the overall discussion, both Waters and Subirats invoked the same, unexpected word and concept that’s at the very core of the matter: comfort.

“Whether you’re talking about having full battens in a mainsail, or when to use a code zero headsail or an asymmetric spinnaker, or whether to reef or not in so many knots of wind, it really comes down to whatever that individual’s comfort zone is,” said Waters.

“Every sailor is different, and they sail in different areas and conditions and wind strengths, and have different goals and ambitions,” said Subirats. “You can have an Olympic sailor who wants every last knot of speed, or a cruising sailor who just wants to go out and enjoy the day and have a swim. In the end, it’s up to you to manage your boat in a way that makes you feel comfortable.”

That said, whether your ultimate sailing goal is to cross oceans, amble through the islands or kick back with a cold one, there are hard truths and facts that must be considered when making the important choices about your sail inventory. Let’s examine some of them.

The Three Tiers

A Brit who grew up in the Middle East, moved to South Africa and worked as a sailing instructor in the wild Indian Ocean, and ultimately landed in the Caribbean as a professional skipper before launching his own charter-company business, Waters has been with the Quantum team since 2016. He approaches the art of making sails in groups of three.

“Call it a three-tier perspective,” he said. “Sometimes I refer to it as the gold, silver and bronze levels, but it goes in three tiers. If you consider the construction and the fabric, they go hand in hand with the tiers as well. The durable, economic, centuries-old, tried-and-true method of constructing sails is cross-cut: literally panel upon panel upon panel going from the head down to the foot, in a horizontal plane throughout the sail. In modern-day sailmaking, the cross-cut fabric is Dacron, a polyester-based woven fabric, in a very simple woven pattern, if you like, with north, south, east and west weaves, with no bias in it.”

Waters notes that one of the key points with Dacron is its durability and strength, which translates to a sail that maintains its cut and shape longer, a benefit he calls “sail-shape retention, which becomes really important to the success of technical sail trim and performance. And performance isn’t just about racing, it applies to a cruising boat as well, because if you have sail-shape retention, you can sail close to the wind with a slightly better boat speed for a longer time, which improves performance. Whereas if you use a fabric that isn’t as strong and stretches out, you’re not going to be able to sail as close to the wind, jeopardizing performance. That’s the first tier and it’s important to point out it’s the most economical tier.”

Waters says the second tier of sail construction is tri-radial: “Which, as the name suggests, is panels radiating from each corner of the sail, the load bearing surfaces, the head, tack and clew. And they radiate towards the central body of the sail, the mid-girth. The purpose of this construction is twofold. Because these panels are in the same direction as the load-bearing surface, the pull on the fibers is less, and their resistance to stretch is better. Because the fibers don’t distort, they don’t get loose, which means better sail-shape retention. In other words, they’re stronger.”

“Tri-radial construction,” he continued, “opens up the largest array of fabric choices, another three tiers of materials. You can build them with Dacron, laminated polyester or carbon fiber. If you go with the lamination process, you’re tending to put more performance into the shape, which means you’re tipping the scale towards the performance end and giving up some of the durability. On the other hand, if you want full durability, you’re probably going to give up a bit of the performance.”

The third and top tier, said Waters, in terms of both fabric and performance, “is a membrane sail, Quantum’s Fusion M range, our signature fabric, which is composite construction. Typically speaking, we’re talking a carbon-fiber sail, though you can use aramids like Spectra or Dyneema or other fabrics. At the high end, however, carbon fiber is used in this laminated, molded shape in Quantum’s product line. We have a racing and cruising range, and the latter gets a lot of its durability and abrasion protection by a taffeta skin that we add. With our IQ design technology, you get an incredibly strong sail with fabulous sail-shape retention.”

A Versatile Sail Inventory

With decisions made regarding fabrics and construction methods, it’s time to focus on the sizes and options with the actual sail inventory. For the purposes of this discussion, focusing on cruising boats and sailors, we’ve narrowed our inventory down to a versatile quartet of sails that will cover all the bases in terms of upwind and downwind sailing over the entire spectrum of wind conditions. Starting aft and working forward, we begin with:

The Mainsail: As far as trim and shape are concerned, other than considering the addition of leech battens, there’s not much to discuss in terms of furling mainsails. “But if you have a traditional, conventional mainsail, there are decisions to be made,” said Waters. “The choices are quite varied, beginning with the batten configuration. You can go full battened, or with a number of mid-length battens down the leech. The advantage with the full battens is that they give you a lot of stability and protection with the sail. It tends to ‘S,’ if you like, every time you tack. With mid-length battens, there’s a lot more unsupported area in the front panels of the sail. But these shorter-length battens mean you can better adjust the sail shape. By easing halyard tension, or adjusting the outhaul or Cunningham, you can dial in different sail shapes, and either power up or depower the sail, which allows you to change the sail’s performance. Then you have to decide how many reefs you want in the sail, which will largely be determined by your sailing plans or ambitions.”

Headsail: Racing sailors generally carry a variety of headsails in a range of sizes and strengths that are set on a foil depending on wind strength and sailing angle. The vast majority of cruisers have a single jib or genoa that’s permanently hoisted on a roller-furling device. The big question here is the size of the sail. Waters said, “The distance along the deck from the headstay to the front of the mast is called the ‘J’ dimension. This measurement helps determine the size of your headsail and in terms of sailmaking, ‘J’ is 100 percent. If you go beyond that and overlap the mast you can go to 110-, 120-, 130-, 140- or even 150-percent, which is really a big genoa-type sail. A non-overlapping, 100-percent jib is small, easy to handle, and offers really good close-winded opportunities. But if the wind gets light you run out of horsepower quickly.” In this instance, there is a solution, which brings us to the next sail in this cruiser’s inventory.

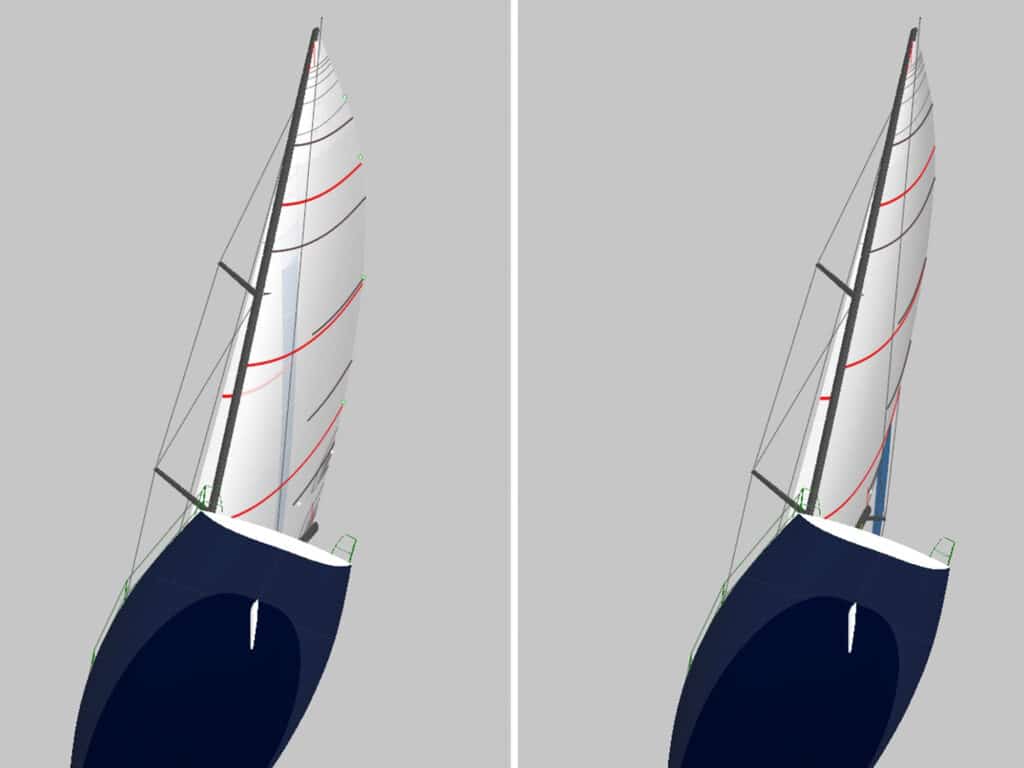

Code Zero: Particularly when sailing off the breeze, on a close or beam reach, a non-overlapping headsail quickly loses its effectiveness. “The code zero is a roller-furled sail that’s built tri-radially that’s very lightweight but strongly built with high-tech fabric,” said Waters. “It’s a really useful sail that can give you a real injection of sail area and shape when you’re reaching, or you can design them so they’ll give you better speed and increased performance when it’s light going upwind.”

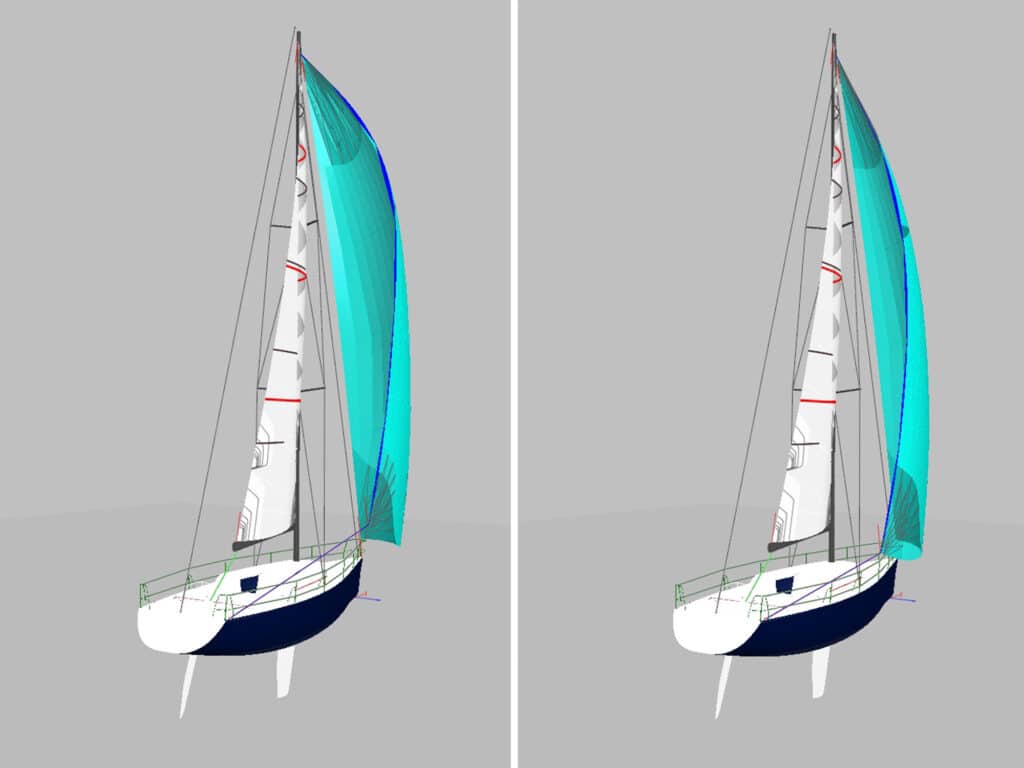

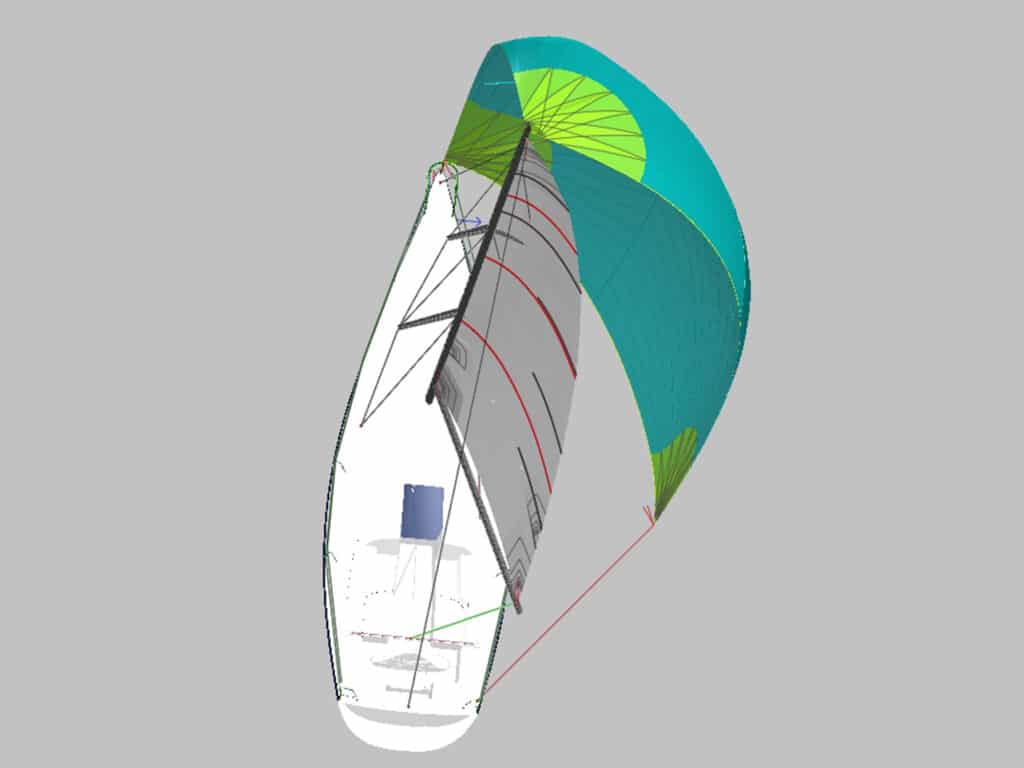

Asymmetric Spinnakers: Once we bear off and sail on a deeper angle, it may well be time to set an asymmetric kite, which for most cruising sailors is hoisted and doused in a dedicated sleeve or sock. “Again, we have different sizes for different wind strengths, normally numbered A2, A3 or so on,” said Waters. “When you have the conversation with your sailmaker, you need to decide if what you want is a running sail, a big downwind sail. Or are you looking for something that’s a bit more versatile, which gives you some reaching as well as running capabilities? Or do you prefer an all-out reaching type of sail? Typically, with a cruising guy, you’ll probably choose an all-purpose asymmetric kite, which gives you a good crossover of reaching and running abilities. Then again, if you have a code zero as well, you might go with a runner.” Decisions, decisions!

Trimming Tips and Techniques

With a pair of engineering degrees and a broad background in sailing and coaching everything from Olympic-class dinghies and one-designs to larger racing and cruising boats, the Spaniard Joan Subirats is Quantum’s go-to resource for, as he put it, “developing the correct tools and software to design and analyze not only the shape of the sails, but their structural side as well.” While that sounds technical, when it comes to actually using sails in real-world conditions, his views and advice are straightforward: “Whether you’re on a racing boat with 15 guys or a cruising boat with your family, correct sail trim is the same. Trim is trim.”

With mainsails, he says, the general outline of a cruising sail is a triangle, while racing sails “have more area at the top, so you have a rectangle configuration.” The defining factor in either, he said, is the roach of the sail, the area along the leech, an important matter in mains with mid-length battens. “If you have a bigger roach, you need to control the twist, which allows you to depower the sail. If you open the leech, you’re basically letting wind pass through the sail and you have less heeling angle. To me, trimming the main is a two-part process: depowering when you need to, and adapting the sail shape correctly to get maximum speed. The basic definition of trim is to adjust the sails to the way in which you want your boat to behave.”

That same theory applies to headsail trim, he said. “At the end of the day, the question is whether you want more or less power in your sails. A racing sailor is obsessed with VMG, the speed made good to the next mark. Cruising sailors, for the most part, aren’t worried about VMG, they just want to maximize their speed to get where they’re going. In both instances, it’s about having more or less power. In light air, you want plenty of it. In heavier air, you want to start depowering, to flatten the sails. The tools to do this—halyard tension, outhauls, jib leads and so on—are the same whether you’re on a racing boat or a cruising boat.” For more information on sail trim and setup, check out Quantum’s mainsail, headsail, code zero, and asymmetrical trim guides.

“I think the general concept for any sailor is simple: what are your expectations for the day, or the cruise? How do you want to sail and enjoy your boat? If we talk to a hundred sailors, we’ll get a hundred opinions, because it’s so subjective. I don’t sail the same way when I’m racing that I do when I’m with my family, even if it’s the same boat. And of course, sailing off the coast of California and sailing across the ocean are two different things. Where you sail is as important as how you sail.”

For more information about sails, visit quantumsails.com/en/sails.