Sailing alone aboard a 35-foot yacht, a wooden ketch named the Temptress, Edward Allcard crossed the Atlantic Ocean — traveling from Europe to New York, and back again — using only the stars and a sextant, surviving on packaged water and meager rations of canned food, cubes of bouillon and the occasional potato.

Mr. Allcard’s two-part voyage, which came to an end when he tied up at Plymouth, England, on July 13, 1951, made him the first person to single-handedly sail both directions across the Atlantic.

He was pursued by sharks, nearly shipwrecked by a hurricane and became an international celebrity when he landed in Casablanca with a stowaway, a 23-year-old Azorean woman who had sought passage to England to become a poet.

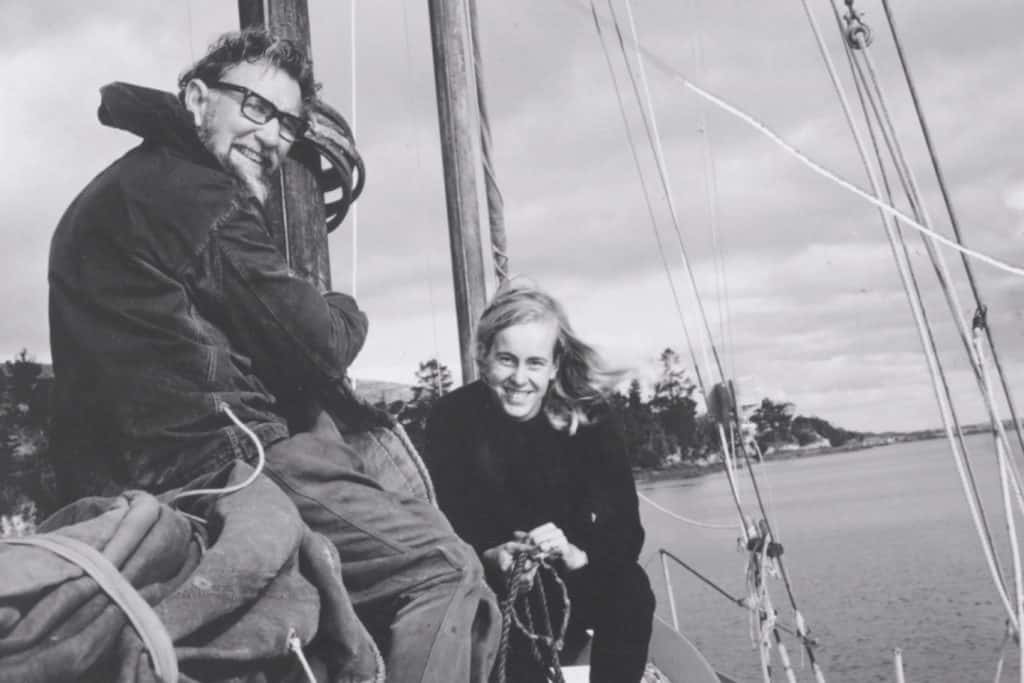

Yet in a life at sea that spanned more than seven decades, Mr. Allcard surpassed his Atlantic expedition with a solo journey around the world. His slow-paced, 16-year voyage included a 12-month exploration of the treacherous waters off Patagonia, in South America, and — after taking time off to meet the woman who became his wife — the birth of his second daughter.

Mr. Allcard, a thick-bearded adventurer whom Boating magazine once described as “the dean of loners,” died July 28 at a hospital near his home in Andorra, a landlocked country in the Pyrenees, where he eventually traded sailing for skiing. He was 102, had sailed until he was 91, and continued writing memoirs of his seafaring life until shortly before his death, publishing “Solo Around Cape Horn and Beyond” in 2016.

The cause was complications of a broken leg, said his wife, Clare Allcard.

Mr. Allcard was considered the last surviving member of what sailing historian John Rousmaniere has called the “the Ulysses generation,” a group of men and women who took to the sea — often alone — in the aftermath of World War II.

Sailors such as Mr. Allcard, his friend Peter Tangvald and the Canadian couple Miles and Beryl Smeeton “were genuine sea gypsies,” said John Kretschmer, a writer and blue-water sailor. “But they were in search of something different from just beautiful or tropical things. They were in search of profound individual experience, and willing to risk their life in pursuit of it.”

Mr. Allcard, who once described sailing as “practically a religion,” was 6 when he learned to sail, and 23 when his boat sank off the coast of Ireland, forcing him to swim to shore. As on later voyages, he had no life raft or emergency radio with which to call for help.

He completed his first major solo sailing trip, from Scotland to Norway, in 1939, and a decade later embarked on his trans-Atlantic expedition. It took him 81 days to travel from Gibraltar, at the southern tip of Spain, to New York.

It was an astonishingly slow cruise by modern standards, but undertaken without the kind of automatic self-steering system that enabled French sailor Thomas Coville, crossing the Atlantic in July in a record-setting four days and 11 hours, to sail through the night with ease.

Mr. Allcard recalled the trip in a pair of popular memoirs, “Single-Handed Passage” (1950) and “Temptress Returns” (1952), which chronicled his tumultuous return journey, including a hurricane near the Azores and his subsequent discovery of the stowaway Otilia Frayão.

The woman, described by one newspaper as a “raven-haired Portuguese poetess,” had offered to help Mr. Allcard clean his boat when he landed in the Azores, and hid inside the hold just before the moment of departure. He discovered her two days later, technically spoiling what was intended to be a single-person journey.

Edward Cecil Allcard was born in Walton-on-Thames, a London suburb, on Oct. 31, 1914. His father was a stockbroker and collegiate rower, and a grandfather encouraged an early interest in sailing, eventually giving him his first boat.\

Read the full story on the Washington Post website here.