Pepe had been drinking again. Oh, boy. It was the fourth time that day that he’d gone over the side, but by now our crew was ready to deal with the problem. “Man overboard!” Jodi called out, not nearly as excited as the first time our “friend” managed to accidentally remove himself from the safe confines of our catamaran. John pointed toward the stern with his right hand, yelling: “I’ve got eyes on him. Two boat lengths!”

With that, the catamaran lurched to starboard as Mike spun the wheel to angle back toward our inebriated crewmate bobbing just above the waves. I was standing on the starboard bow pointing the business end of a worn boat hook at Pepe so our captain could position us for the rescue.

As we closed in on Pepe, hand signals were flashed, the diesels slipped into neutral, and I lunged forward to snag our waterlogged victim. Pepe—a small fender to which a kedge anchor was attached—was not actually a drunken sailor, or even a human one. As I hoisted him (it?) on board, instructor Tim Jenne nodded with satisfaction and calmly said: “Great job, everyone. Let’s do it again.” As we all changed positions, Pepe backed down yet another imaginary one and was once again hurled into the sea for the next in an ongoing series of man-overboard drills.

Some guys never know when to say when.

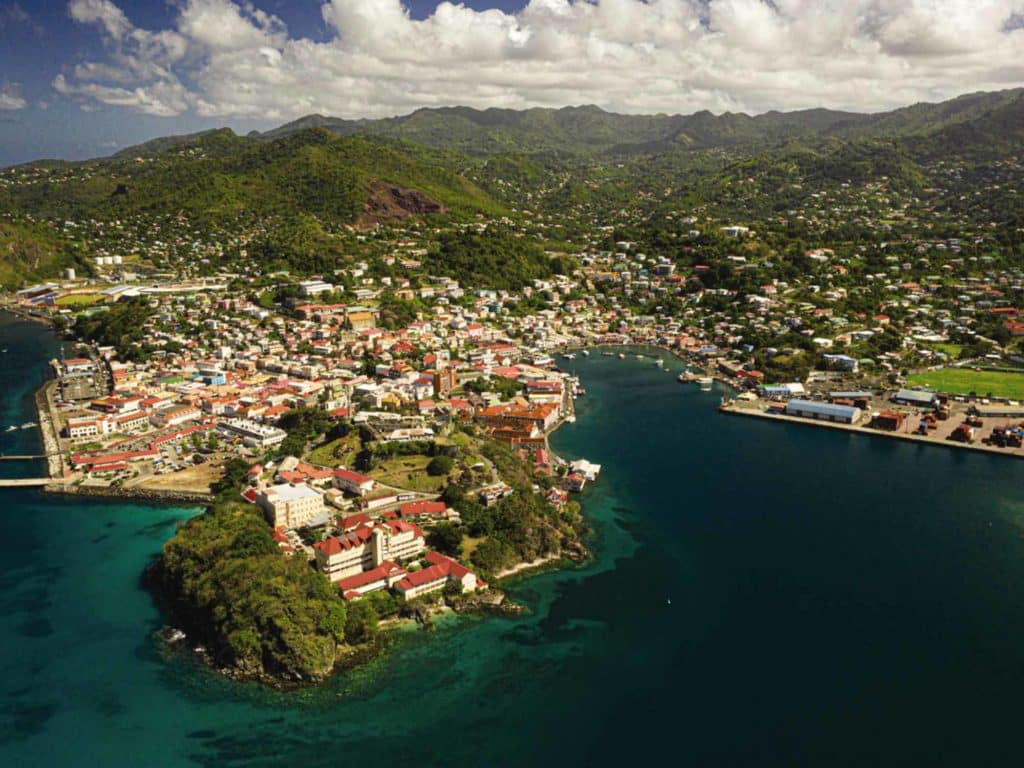

We were practicing a little less than a mile from the southwestern shore of Grenada. The austere gray walls of Fort George stood high on a hill protecting the colorful Carenage and harbor below. Blue waters rose to meet the sandy shoreline, which ascended again to trace walking paths through the lush chaparral foliage. Picture-postcard Caribbean homes dotted the foothills like errant brushstrokes from a vibrant palette. Above it all stood the impossibly green mountains, remnants of massive volcanoes that bloomed from the seafloor to create this Eden. The remains had given way to rainforests visible only when the swirling shroud of clouds at the summit dissipated. When the wind swept down the overgrown slopes, a fleeting scent of exotic nutmeg and cinnamon tickled the senses; this is the Spice Island, after all. I still had to pinch myself that this was my classroom for a week.

I considered myself lucky to be part of a liveaboard sailing course offered by Nautilus Sailing, an ASA-affiliated sailing school founded by Tim Giesler in 2010. Giesler had learned to sail in Southern California, and at the outset, over the course of a two-year period, took lessons from more than eight instructors.

“They were very accomplished sailors, but sadly were not natural teachers,” he remembered. “I was disappointed at what passed for ‘instruction.’ Just because someone has a ton of sailing experience doesn’t mean they can effectively break down complex skills and material and teach people how to sail.” With a strong background in education that involved teacher training and developing experimental education programs, he knew there must be a better way to train new sailors. Nautilus was born, and a partnership with Dream Yacht Charters now allows its instructors to teach formal ASA sailing courses in exotic locales across the globe such as Tahiti, Mallorca, the Sea of Cortez…and, of course, Grenada.

Nautilus offers a curriculum designed to both cater to individual student’s needs and also to ensure that the instruction doesn’t get in the way of the fun one should have while sailing. Because the class takes place entirely at sea on a catamaran, each student is completely immersed in sailing concepts every moment of the day…and later, at night over drinks. All of this occurs in a paradise of tropical sunrises and sunsets, and stargazing late at night in picturesque anchorages.

RELATED: Sailing into Camp Grenada

But make no mistake: It’s an intense course, covering more than 100 practical skills with four written tests. By the end of the week, students receive ASA 101 (Basic Keelboat), ASA 103 (Coastal Cruising), ASA 104 (Bareboat Cruising) and ASA 114 (Catamaran Cruising) certifications. That’s assuming you’re a good student.

Which, it must be said, I most certainly am not.

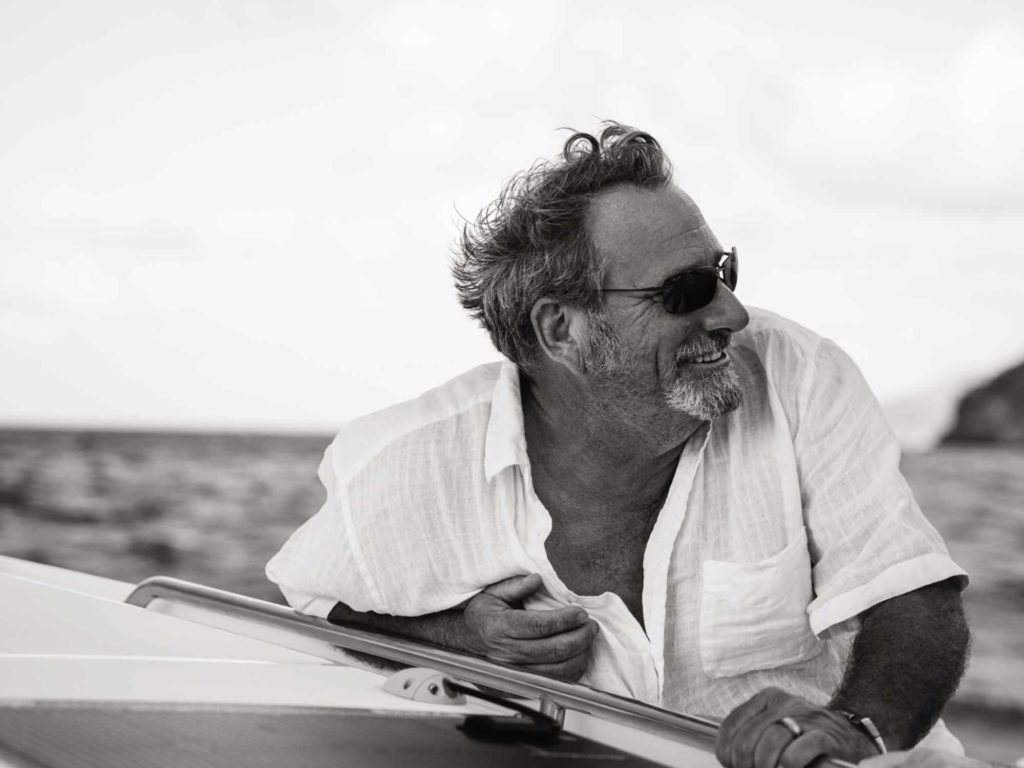

Enter Tim Jenne, my instructor for the week, whom I didn’t envy for having to put up with my smart-aleck lack of preparation. Jenne is the quintessential old salt: a Navy brat, former member of a US Coast Guard rescue team, and sailor since the age of 13. He had that look you’d expect in a man of the sea: sun-bleached brown hair and a tan face broken up with white lines from his ears to his eyes where sunglasses have left a lasting impression.

Jenne was soft-spoken and calm, with a reassuring manner that almost made you believe he’s the most mellow human being you’d ever encountered. But if you watch him long enough, you’ll see that he never stops moving or scanning the horizon or calculating the next move that needs to be made. There’s never a moment when Jenne isn’t behind or beside you, ready to offer assistance or guidance. He believes in getting to know each student’s way of learning, and then instructing in a sequence of telling/showing/doing/discussing. When teaching a new skill, he tries to set up everyone in 20-minute rotations to provide ample learning time and a buffer to absorb it all. It’s another tenet of Nautilus‘ educational playbook.

Three other students joined me on the adventure: Mike, a commercial airline pilot from Canada, and John and Jodi, a couple who worked as a contractor and registered nurse, respectively, and who split their time between Ohio and St. John in the US Virgin Islands. We’d come together aboard a Lagoon 40 from Dream, with various seagoing dreams and plans. Mike was clearly ahead of everyone, and if there were a grading curve in this class, I soon realized he was destined to screw it up for all of us. He’d obviously read the material ahead of time, as we’d been advised to do during the ample communication from Nautilus before the start of our trip. From there it went slowly downhill in the preparedness department…from John to Jodi to me. That said, I’m no stranger to being last in the class, and Jenne was no stranger to teaching a problem child.

The first few days of the course unfolded rapidly; there was no shortage of information to be learned, forgotten and learned again…correctly this time. Before we’d even left the dock, each one of us had already been in the engine compartments checking filters and fuel levels, and filling out logbooks. Before our very first sunrise together, we’d already tied multiple knots to every available surface (knots, it seems, is a fascinating topic among sailors). And each morning began with one of us being promoted to “captain” for the day, which meant plotting the course to our next destination, assigning crew to individual duties, and keeping track of the systems and status of our vessel. During those times, Jenne would always be about, silently watching, ready to jump in if need be while still allowing the students to be in complete control of our collective destiny.

When the wind swept down the overgrown slopes, a scent of nutmeg tickled the senses. This is the spice island, after all.

For two blissful days we’d been underway, but a stunning sunrise on the third morning heralded the arrival of the first of the dreaded exams. The title, ASA 101, loomed above my reading glasses like a grim specter sent to ruin a perfectly good day. Jenne had already done an in-depth review with us over a stout cup of coffee, but again I found myself revisiting the practice test again and again. “We should get this finished so we can go sailing,” Jenne suggested gently, but we received the message loud and clear: It was go-time. And so we gathered around the table and passed around a bag of pencils. Jenne handed out laminated copies of the test, and we were off.

Our catamaran gently swung to and fro against the mooring ball we’d picked up the evening before. Without question, as the waves sighed peacefully along the beach of the aptly named Sandy Island, beside which we’d spent the night, we’d stayed in the most distracting classroom on the planet. Resembling a long, flattened lowercase “j,” the island is no more than 20 feet across at its narrowest point and barely a few feet above sea level. Palm trees dot each end of the shoreline, and just offshore, millions of small baitfish skip across the water trying to outwit prey while pelicans crash into the water from above.

The occasional monohull or cat appeared to claim or leave a mooring ball, which inevitably led to our peanut-gallery observation of his or her skills. “Oof. That’s not going to go well,” someone would say quietly as we all prairie-dogged up to take a look. Or, more rarely: “This guy knows what he’s doing…” And as I refocused my attention on the task at hand, a strange sensation came over me: I know this stuff. The anxiety began to fade as the lessons of the past few days became clear. Before long, I was finished…and had passed with flying colors.

I did not do as well as Mike, however. Nobody ever does.

With the first of the gauntlets behind us, we gazed out at the open ocean, suddenly made textured by the steadily increasing winds. The rigging sang quietly as veins of breeze appeared on the surface of the water around us. “It’s a good day to sail,” Jenne said happily, and with no further direction, we each took up a different position on deck. Moments later, the mooring ball had been dropped and we’d motored away from Sandy Island to hoist the main. Again the thought struck me: I could be sitting in a classroom watching learn-to-sail slides, but here we are taking spray in the face and helplessly smiling. It truly was the way to learn.

Days four and five passed similarly, with repetitive drills and shared captaining duties. We practiced mooring and anchoring in the ever-present trade winds, followed by sailing in circles offshore to feel the boat power up and down with every adjustment we made. We rotated between roles, no matter what the activity, with each person getting plenty of time to learn and understand.

For every hard few hours of action there was a following, and welcome, respite. We snorkeled alongside vibrant Caribbean reefs and walked on tiny, deserted islands. Dramatic scenery slipped past as we sailed between massive rock formations that jutted up from the deep blue channel that ran between them. And one by one, the tests arrived and were completed. I kept repeating the old joke in my head as a way to combat the anxiety: “What do you call a guy who gets a ‘C’ on his sailing exam? Sailor.” But Jenne’s unflagging patience and attention were paying off. I watched him as he graded the tests in the saloon, nodding silently that his students were becoming sailors.

Suddenly the radio crackled to life with the last words any of us expected to hear: “Mayday, mayday, Mayday!”

It had been a beautiful morning sailing south from Tyrell Bay on Carriacou toward Grenada, with strong winds to assist in the journey. We’d been running a fishing line off the port quarter the entire week without any bites, but on this day, a dorado took the lure, giving us a chance to heave to and catch lunch. Jenne filleted the fish on deck, and we enjoyed the freshest sushi one could ever hope to devour before continuing on our reluctant journey back to the mainland. The sense that this experience was coming to an end was palpable, and every so often the crew would simply go silent, breathing in the sights and sounds that would soon be behind us.

As we approached Grenada, the breeze began to pick up considerably, nearing gale-force conditions. Our destination was Molinere Point, the site of one of the most beautiful underwater sculpture gardens in the world. The plan was to pick up a ball, do a little snorkeling and have our final lunch together, but the rising seas and deteriorating conditions suggested a change of plans.

Suddenly the radio crackled to life with the last words any of us expected to hear: “Mayday, mayday, mayday!”

“Write down those coordinates,” Jenne said as he grabbed the radio to respond, but we quickly realized there was no need to plot a course; the emergency was right here at Molinere.

“Two people recovered,” the voice on the VHF continued, her voice trembling. “Unsure if there are more in the water.” I grabbed our binoculars and ran from the saloon to the bow of the catamaran and began sweeping the horizon.

After locating the boat that had made the distress call, I slowly scanned the turgid blue and white water between us. John appeared on deck beside me and said loudly, “Cooler, there!” I searched and spotted a floating Igloo, and not far from that, a tan, wooden gunwale and a paddle just below the waterline. A tangle of net still clung to what was left of the sinking fishing boat, but thankfully there were no other people to be found. With Mike at the helm and all eyes on the water, we continued to search the area for any more survivors. The radio crackled to life again: The two recovered fishermen were the only ones on the sunken boat, and coordinates for the vessel were called in to the Grenadian Coast Guard.

We managed to find calm water and an open mooring along the shoreline at Molinere to catch our breath and let the tension from the morning slide away. We slipped into the water and snorkeled through the now-famous underwater sculpture garden installed by Jason deCaires Taylor. Shadowy figures loomed out of the stirred-up sand along the bottom. Shapes—some whimsical, some disturbing—appeared below. A circle of stone humans held hands with their backs to the center, coral and algae covering their bodies. Colorful fish darted from limb to limb, seeking safety.

My head cleared and I was able to reflect silently on the importance of the skills we’d all learned this week, all of which were given a different level of importance after answering a mayday. But I knew this meditation had to come to an end: The final test would soon be upon us. The decision was made to head back in to St. George and do some docking practice in the fresh breeze to round off the experience. Then, finally, we were back at the marina.

There’s no point in any further suspense; Jenne trained us well, and we all passed the final exam, with the exception of Mike. I’m kidding, the teacher’s pet ended as he began—impressively. I stood over Jenne as he signed off on each course in my newly acquired logbook, filling in the blank space where my certification seals would eventually be placed. I was filled with pride; I honestly didn’t think I’d make it this far. But I did. We all did.

The final numbers of the trip were straightforward: 117 total nautical miles. Max boat speed: 10.6 knots. Max wind speed: 34.8 knots. ASA courses complete: four. But none of these numbers really represents what an experience it was, and no retelling of the tale could ever represent what it was like to be there. But the beauty of this class at sea wasn’t just to learn, but to build a platform for future memories as well. And thanks to Nautilus, there will be no shortage of those on the water for years to come.

It was time to find Pepe. Cocktail hour was calling.

Well-traveled rogue and bon vivant Jon Whittle is a staff photographer and videographer for Bonnier Corp.

To learn more about Nautilus Sailing, visit nautilussailing.com or call (800) 680-7902.