The most useless item on a cruising boat? A calendar.

I can’t recall how often I’ve heard and agreed with this quasi joke. Unfortunately, though it is mostly accurate, it doesn’t take into consideration time frames imposed by natural seasons, plus the pressures of the human-created ones. And twice now, when I’ve been voyaging in Australian waters, a combination of the two have led to more-dramatic sailing than I truly enjoy.

In 1988, Larry and I decided to take a break from fixing up the small run-down cottage and boat shed we had purchased in New Zealand to sail over to rendezvous with cruising friends at Townsville, Australia: a great way to avoid winter, and to explore a bit of the Great Barrier Reef. At the same time, we were in contact with several other friends who were cruising through Polynesia and planned to head south to New Zealand to avoid the tropical cyclone season. It seemed only natural to invite them to spend Christmas at our first-ever “home base.”

So, between the natural calendar events (i.e., changing weather systems) and our “human-created” calendar event, we ended up caught in the worst storm of our lives as we tried to fight south out of the Barrier Reef so we could head for home before the cyclone season and in time for Christmas. (We were caught in a “squeeze zone”: a ridge of high pressure wedged against a stationary tropical low.) Obviously, we survived. Obviously, it didn’t turn me off to sailing. Obviously, we tried and mostly succeeded in avoiding being pressured by calendars after that. But now….

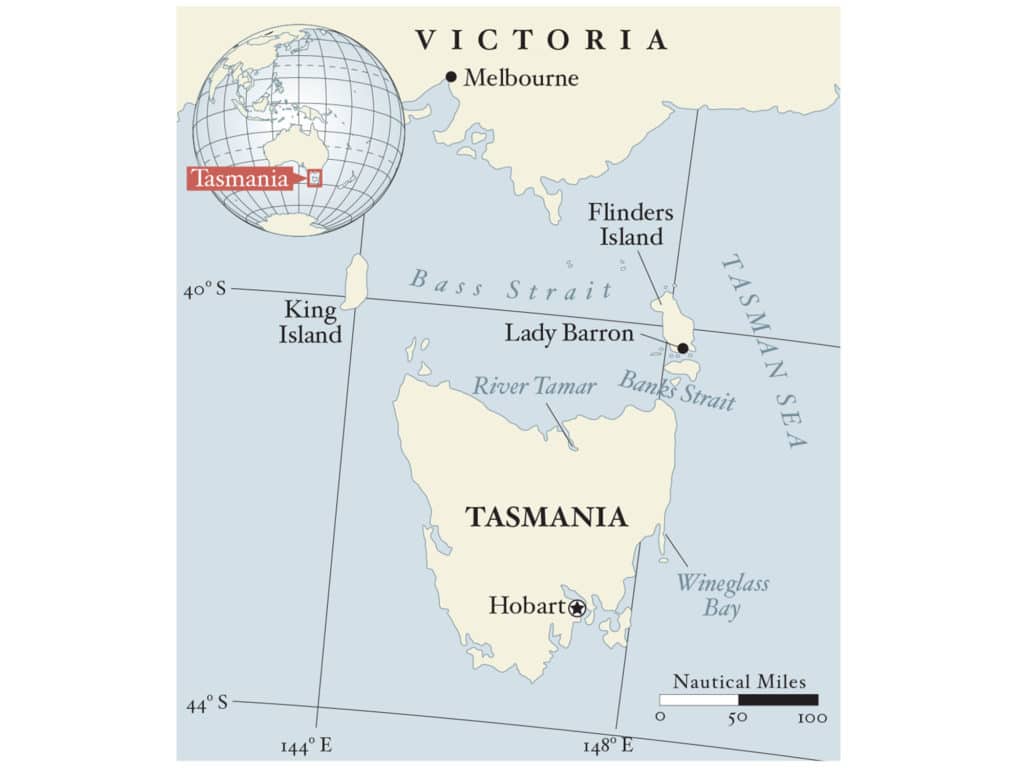

David, who I have voyaged with since 2017, is from Australia. He has three grown daughters living in scattered places. One has a home and slowly expanding family in Melbourne. This definitely influenced our plans. Since David often talked of exploring some of the isolated bays and hiking trails of Tasmania, I agreed: “Let’s go! We can sail across the Bass Strait to Melbourne and have our own home with us for the Christmas season.” His young granddaughter could come on board and play. We could play host part of the time and not be underfoot when little ones got overtired. So, a year ago, after cruising from New Zealand through the islands of Vanuatu and on to Australia, we sailed Sahula, David’s Van de Stadt 40, south to Hobart, Tasmania.

Despite being in the Roaring 40s, we had good winds or good anchorages to hide in as we explored the islands and rivers south of Hobart. Even when we meandered around the bottom of “Tassie” to the truly wild west coast, we were able to find well-protected places to wait out the occasional strong winds that blew in from the west, especially as the only calendar influencing our decisions was that created by the weather systems.

We left Sahula safely sheltered in Kettering, just south of Hobart, for several months while I worked in New Zealand to finish a book project, then we traveled to the US to launch it into the world. (It was late summer in the Northern Hemisphere but still winter in the Southern.) Sometimes, in our land travels, I looked at my preferred weather app (windyty.com) and felt pleased to be away from the wild winds and freezing temperatures of the Tasmanian winter.

I reassured myself, when summer in Australia approaches, the high-pressure systems tend to move south and shove the Antarctic lows below Tasmania. That’s when the winds should turn light, the weather kinder. Besides, we only had to sail north, then west, about 400 nautical miles. I checked my mental calendar again. Yes, once we returned to the boat, there would be at least nine weeks to make the journey, with several interesting islands to visit along the way. If we got a bit late, all we’d need was a three-day patch of good weather and we’d be home and hosed, as the Aussies say.

But the reality proved different. Once back in Oz, both calendar events and natural events colluded to provide what can only be called “interesting” sailing.

Instead of the two weeks we’d planned, due to weather and the inevitable extras that always seem to pop up, we needed four weeks to get the boat ready to go after her winter storage. Then the weather turned foul, just when we were ready to set sail. Each Tasmanian we met said, “Worst springtime we’ve had in years.” That was of little solace as we slowly chewed our way north, eating up day after day of our mental calendar by hiding in various nooks and crannies from the often storm-force headwinds. As much as we reminded ourselves, “This is cruising; relax and enjoy this anchorage,” we couldn’t.

Each day we’d scour the weather forecasts looking for that elusive weather window. We worked north until we were sheltered amid the wild beauty of Wineglass Bay. For four days, we checked the forecasts the minute we awoke, at noon and at 6, but the weather failed to cooperate. Low after low marched right through the Bass Strait, sending gale-force headwinds our way. Then we both spotted it: the promise of a fresh southerly breeze to speed us north to Flinders Island at the entrance to the Strait. Three different weather models concurred: 16 to 18 hours of fair winds, maybe blowing up to 25 knots, then easing off for several hours before turning to gale-force westerlies. With only 115 nautical miles to cover, it appeared we’d have plenty of spare time to reach a safe spot before the big westerlies filled back in.

At 0100, we were both wide awake. “That northerly wind has dropped off—let’s go,” David said. Bundled up against the cold, we headed out. We soon found that the wind had mostly abated but the sea hadn’t. We kept going, engine roaring, mainsail doing nothing at all. By daybreak there was no sign of the “fresh south wind” forecast by the Met office. But an hour later, I pointed out dark water to the south.

The engine was shut down with the first gusts, the yankee set, and we were soon scudding in front of a breeze that rose so quickly that within minutes we were reefing down, then reefing some more. Soon, we were running under staysail alone before 32 knots, gusting to 40. At first it was exciting, feeling the boat respond perfectly to each adjustment of the wheel. Then, as we approached the entrance to Banks Strait, the waters rushing from the Indian Ocean through the Bass Strait and curling around the islands and into the Tasman Sea, we began to bank up against the southeast gale-force winds.

Had we been in deeper water, I am pretty sure this could have been just exhilarating sailing. But as so many Sydney-Hobart racing sailors have found, the continental shelf extends far offshore here, and with only 40 meters of water, the seas become short and steep. The autopilot couldn’t cope. Nor could the self-steering vane. It became imperative that someone helm the boat carefully. I tried spelling David to find I could do only 20- or 30-minute stints because of our height difference. The helmsman’s seat on Sahula is built for someone 6 feet, 2 inches. I am only 4 feet, 10 inches and can’t reach it to steady my body as I control the wheel. “We have got to get a wooden step built for you as soon as we get to Melbourne,” David said after helming for almost nine hours straight. (I plan to hold him to that promise.)

The winds neither abated nor shifted to the west as we approached Flinders Island. This presented a worrisome new problem. There is a bar across the entrance to Lady Barron, the small port on Flinders. All the information we had showed that the leading lights should give us at least 4 meters of water at high tide. But the bar is known to shift quite dramatically. I began to be concerned that, with this wind, the bar could be breaking. If the entrance was impassable, we’d have to lay offshore, maybe for as much as 12 or 15 hours, and hope the winds eased or changed because the charts showed no other anchorage that would provide shelter in these winds.

Then luck and modern technology gave us the break we needed. Though no one answered our VHF call, one bar appeared on my cellphone. Google gave me the number of the port manager at Lady Barron. “No fishermen working out of here anymore. Ferries use the eastern entrance,” Garth told me. “So no idea of what the bar is like or where it actually is right now. But you might check out the hook at Harley Point. Some of the fishermen used to shelter there when things weren’t right.”

There is a strange feeling of disconnect when the seas suddenly seem to disappear as you round a wave-swept, barren point to encounter almost calm water. Yes, the gusts of wind still screech around you, and yes, the scud of clouds overhead show the gale still rages. But as you feel the anchor grab the bottom and the boat settle back, then you realize you’ve found a secure—if not absolutely steady—place to wait till things calm down, and the adrenalin charge that kept you performing fades out. Then, an almost giddy sense of accomplishment kicks in. Sails fully secured. Engine off. Hot soup boiling on the stove. Wind forecast to abate and change to the west in the morning. We both felt this giddiness and at the same time, a wonderful sense of accomplishment.

This sailing definitely hadn’t been fun. Being pushed by the calendar lured us out in winds we’d rather have avoided. But we’d done it, worked together as a team, and experienced some of the winds and seas that give the Bass Straits its well-deserved reputation.

Being pushed by the calendar lured us out in winds we’d rather have avoided.

And now the calendar felt less pressing because we had three weeks before the family started gathering. There was still more than 150 miles to go. But now there were signs that things would improve, with the next high-pressure system definitely farther south than the past ones.

We’d soon be on our way again. We both agreed, once the holidays were over, we would avoid having the pressures of a calendar or schedules, and instead set only flexible goals. But as I was writing this, a note arrived from friends back at my island home in New Zealand. It read: “You planning to be around during the America’s Cup? Lots of fun parties and races planned for around the island.” The mental calendar clicked in. More than 10 months to get there, only 2,500 miles….

A final thought: Crossing the bar after a good night’s sleep and with the wind more to the west was a bit on the dramatic side but presented no true dangers. We stayed only one day at Lady Barron because a favorable wind kicked in. A relatively benign 12-hour beam reach got us halfway through the Bass Strait to the River Tamar on Northern Tasmania, where we then motored 20 miles inland to the delightful small city of Launceston. A successful passage after all.

Voyaging legend Lin Pardey has spent the season sailing in Australia and is currently planning a return trip to her home in New Zealand. This past summer, her husband, Larry, passed away after a long illness.

Cruising the Bass Strait

Challenging? Yes. Interesting? Definitely. Unfortunately, few visitors to this area of the world take time to explore the islands and anchorages of the Bass Strait. Instead, sailors head south from Sydney to Tasmania to wait for a good weather window in Port Eden, then dash across the straits to beautiful Wineglass Bay. From there they enjoy day-hopping toward Hobart. It’s sort of sad, because the islands of the strait, and the rivers and small fishing ports of Northern Tasmania, can offer the uncrowded, off-the-beaten-track experiences most of us yearn for. But cruising here requires good timing, patience, appropriate anchoring gear and some local knowledge.

Though I have met hardy Melburnians and Tasmanian sailors who talk of year-round cruising here, for those who are looking for less-challenging sailing, here’s a short weather primer. This is the Roaring 40s, an area of strong westerly winds and frequent fast-moving low-pressure systems that sweep right around the bottom of the world. Lows tend to compress as they try to push through the strait, turning gale-force westerlies into storm-force tempests. To add further drama, the waters between mainland Australia and Tasmania lie on top of an ancient land bridge. Nowhere is there more than 150 feet of water, and often there is less than 60. So, even moderate winds can create steep seas. The shallow water also exaggerates tidal and ocean currents, which, at the eastern end of the strait, can run at up to 5 knots.

Fortunately, during late summer and early fall, the high-pressure systems that usually dominate mainland Australia migrate south. This provides much milder wind conditions, and also breaks the predominance of westerlies. Though this southern migration can happen as early as mid-December, February and March provide the best chance of fine weather for exploring the Bass Strait islands, small ports and rivers along northern Tasmania. For several years, the Royal Yacht Club of Tasmania has hosted a Round Tasmania rally in mid-February every two years. More than 50 boats take part in the monthlong 800-mile event. To date, rally participants have never been kept in port for more three days due to inclement weather.

Due to the downturn in fisheries in the Bass Strait, VHF communications with harbor authorities among the islands and in the small ports is limited. As noted, we had more luck using local phone numbers provided in cruising guides.

You will be highly dependent on your ground tackle out here. A few places such as Lady Barron anchorage on Flinders Island and Grassy Bay on King Island have guest moorings available for visitors at no cost. Unfortunately, these steel moorings are designed for big, rough fishing boats. With wind against tide, you are almost guaranteed to suffer topside damage if you choose to use one.

Especially among the islands, sea grasses and kelp can make anchoring difficult. The preferred anchors among Bass Strait cruisers are a fisherman-type with sharp fluke ends that can dig through the kelp to find the sandy bottom below. If spending a whole season cruising here, I highly recommend adding one to your arsenal.

Cruising Victoria, a Guide to Cruising Victoria, the Bass Strait Islands and Northern Tasmania by the Cruising Yacht Association of Victoria definitely provided the most complete information. We relied on windyty.com and deckee.com for weather planning. The latter also provides tidal information based on your actual location. As tidal changes can be up to an hour different on opposite sides of larger islands, we found their info extremely useful.

If you are dreaming of an endless supply of the famous Bass Strait crayfish, put on your diving gear. Fishermen will not sell to you cheaply because the price has skyrocketed. Crays were priced at 120 AUS per kilo ($40 a pound USD) when we reached King Island.