In Jules Verne’s science-fiction classic Journey to the Center of the Earth, the entrance to the underground world is in western Iceland, at the top of the ice-covered Snæfellsnes volcano. His explorers have many fantastic adventures underground, encountering giant beasts and taking a punishing sail through a raging subterranean sea.

So when our two chartered 50-foot Bavaria sloops rounded the tip of the mystical Snæfellsnes Peninsula this past June, in the shadow of the volcano, we were not surprised to see some fantastic (but real) beasts: A huge whale—probably a minke—breached off the stern, large pods of orcas and dolphins passed by, and countless beautiful North Atlantic seabirds soared around us.

And when the inevitable Arctic winds kicked in from the north a day later, it almost felt as though we too could be sailing in a storm at the center of Earth.

Here’s how Verne described it: “Low clouds and fog, heavy wind and seething waves, a sunless, engulfing dull grey haze.” In the novel, it got toasty down below, so his sailors were warm; but it was bitterly cold up on the surface in the real world, and we piled on all the warm and heavy-weather gear we could muster.

Our group of a dozen friends had come here to spend two weeks sailing the incredibly beautiful coast of Iceland, where everything is—or quickly can become—extreme: the winds and ocean rollers, tides and currents, temperature, and an unforgiving volcanic shore. At the time of our visit, while various outfits offered crewed charters, only one company, Iceland Yacht Charter, was willing to rent its handful of yachts as bareboats to private sailors without a professional captain and crew, although the charter captain had to be licensed.

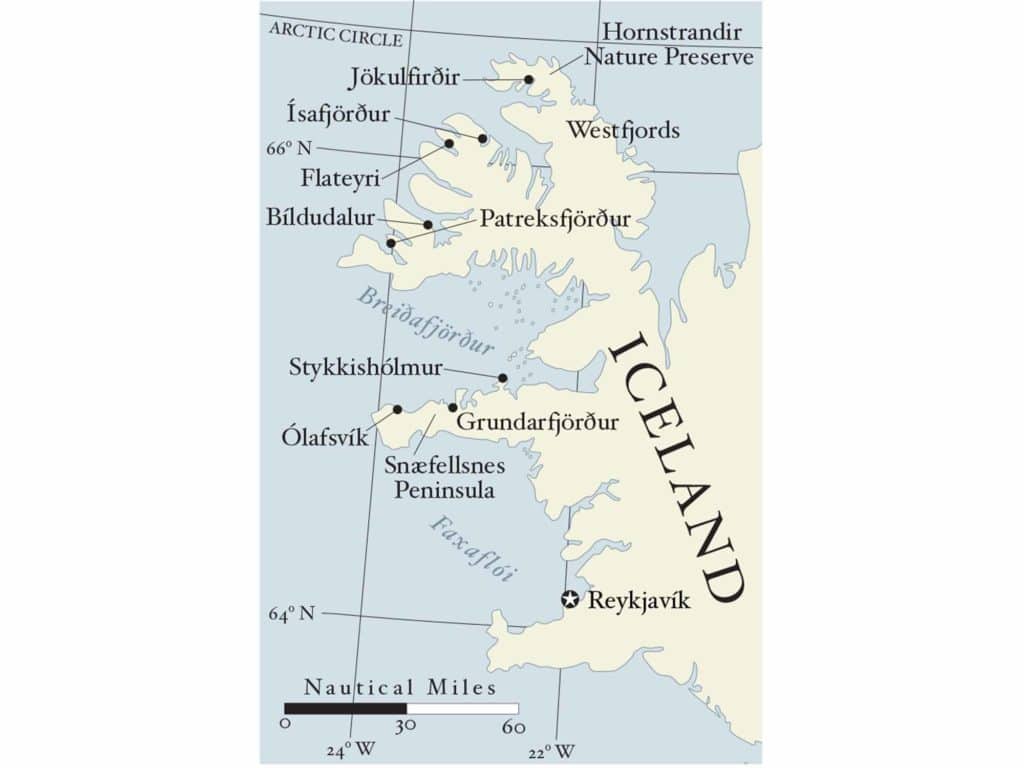

If you want to sail in Iceland but don’t want to make an ocean passage to get there, bareboat chartering is the next best way to go. There’s just one cruising ground, but it’s big: the western coast. Sailors set off from the capital city of Reykjavik, and head north toward the remote Westfjords and the Arctic Circle. The southern coast has no natural harbors and is swept by dangerous currents. The entire northern coast is a lee shore to Arctic winds blasting down from the North Pole, and can be mined with icebergs that drift over from glaciers calving off the coast of Greenland, some 300 miles to the northwest.

Our crew gathered and held a long safety briefing before setting off, emphasizing Rule No. 1: Once we left the dock, nobody left the cockpit unless tethered to a jackline. Going overboard while underway would be a death sentence.

“Anyone sailing here should be prepared for the conditions—strong winds, big seas and tides, cold weather—and should be self-sufficient,” says Jay Kenlan, a Vermont lawyer and licensed captain of our boat, Esja. “The reward is the beauty and remoteness of the place.”

Adds Ben Gardner, a New Hampshire physician and our first mate: “The crew needs to be people who understand this is not a warm cruise around a sunny lake. You are going to be cold and wet.”

There is virtually no cruising or chartering infrastructure outside Reykjavik. The commercial-fishing industry dominates the coast, and every harbor is industrial. We tied up every night to vertical steel bulkheads protected by old tires, clambering up and down wall ladders to get on or off the boat—sometimes 20 feet, at low tide. With no recreational marinas, we used local public swimming pools to shower (there’s one in almost every town, and it’s a terrific way to meet locals). In two weeks, we saw only four other sailboats; cruisers are rare up here, which opened some wonderful conversations with local Icelanders who were surprised to see us.

One night, because the local harbormaster needed all the bulkhead space he had for fishing boats, we rafted up to a 100-foot steel fishing trawler. Getting ashore meant scaling its hull ladder and crawling over the heavy-duty dragging gear sprawled across the deck.

So why go? For experienced sailors, a big attraction is that it’s not just another sodden tour of Caribbean beach bars. Iceland suffers from bad overtourism in summer (especially around Reykjavik) and the nearby Golden Circle attractions, so exploring by sailboat is the perfect way to escape the crowds and traffic jams. If you want to see the incredible natural beauty of Iceland and meet locals in a way few visitors ever will, setting your own course in your own boat is a deeply rewarding experience. You earn your vistas.

A Volcanic Hotspot

Iceland floats atop a volcanic hotspot in the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, between the American and Eurasian tectonic plates. Spreading apart a few millimeters each year, these shifting plates produce extremely active volcanic activity.

On the west coast, part of the defining geography created by these forces is the long and narrow Snæfellsnes Peninsula, which lies across Faxa Bay, or Faxaflói in Icelandic, roughly 90 miles northwest of Reykjavik. Farther north, across another big bay called Breiðafjörður, or widening fjord (and looking vaguely like a lobster pointing toward the North Pole), are the craggy and starkly beautiful Westfjords. Geologically, this is the oldest part of Iceland, and by far its most remote and interesting corner to explore, with sharp mountains, flat volcanic mesas, deep waters and a heavily indented coastline.

With a big cold front forecast to drop out of the Arctic within three days, our two boats pushed out of Reykjavik as hard and fast as we could to get as far north as we could. Day one was 100 miles, to the small fishing town of Ólafsvík, on the north shore of Snæfellsnes; luckily we had a rare clear day, revealing the dramatic volcanic glacier as we rounded the tip of the peninsula.

That was followed by an 80-mile push into the southern end of the Westfjords and another small fishing village, Patreksfjörður (Patrick’s Fjord). Day three was a final 80-mile slog through building weather to Ísafjörður (Ice Fjord), one of the northernmost towns in all of Iceland and the largest in the Westfjords.

That night the crews of our two boats celebrated our arrival with a warm and lively communal dinner. The chef aboard Katya cooked up fresh-caught salmon, while Esja provided baked potatoes and salad. The well-lubricated evening was capped off with rounds of Shackleton scotch, a modern blended malt re-created from the three cases of original century-old whiskey discovered in 2007 frozen into the ice under Earnest Shackleton’s base camp in Antarctica.

A major fishing center in the region, Ísafjörður is home to the terrific Westfjord Heritage Museum, which depicts the harsh and bleak life of early fishermen there. It is attached to one of the best seafood restaurants in Europe: the Tar House, set in a beautiful, old post-and-beam fishing shed. With only two seatings a night served buffet-style on heavy picnic tables, the meal started with rich lobster soup, followed by several huge cast-iron frying pans filled with magnificently prepared fish, all just hours out of the water: cod, salmon, halibut, haddock, and others I did not recognize. Epicures from all over the world come to eat here, and we stumbled into it by luck.

After a lay day exploring the town, our two boats separated, Katya turning back south to keep to a shorter schedule, while we pushed farther north. This was our shortest leg of the trip—a motorsail of just 18 miles—and took us into a narrow and extremely remote branch of Jökulfirðir (Glacier Fjords), in the Hornstrandir Nature Preserve, just below Iceland’s northern coast.

This was the day the bad weather arrived, spitting cold misty rain, fog and strong northeast wind. As the day’s muted light began to fade, Iceland’s renowned “magnificent desolation” in the far north seemed to become just gray, grim, barren and bleak, and intensely lonely, punctuated with blasts of stingingly frigid wind. And it’s a long day of light in Iceland in June: Anchoring at 66 degrees 21.5 minutes north, 22 degrees 26.8 minutes west, we were less than 10 linear miles from the Arctic Circle and the never-setting midnight sun.

Given its volcanic nature, Iceland can be a hard place to anchor. There is precious little soil above or below the water, so the flukes don’t always dig in well. Although we finally got a good set after several attempts, a powerful williwaw hit around 0200 and pushed our boat hard over, dragging the anchor. With about a football field to spare from grounding on sharp lava, we motored back upwind. After several failed attempts to reanchor, we gave up and motored out.

Heading South

Once we left the cover of the fjords and entered the open sea, the strong Arctic wind quickly produced our wildest day of sailing, with 25-foot seas and a full gale at our back. Thus began our hopscotching down the coast of the Westfjords. Our first stop was the small fishing village of Flateyri, a former whaling station that lost 20 people in a snow avalanche in 1996, a tragic record for Iceland. Next was Bíldudalur, home of Iceland’s wonderfully tacky Sea Monster Museum, and, not coincidentally, the site of more sea monster sightings than anywhere in Iceland. It’s worth the price of admission just to see all the misspellings and leaps of logic in the exhibits, let alone the life-size monster models.

After a return trip to Patreksfjörður, we left the Westfjords behind and spent three days exploring the north shore of Snæfellsnes Peninsula, a notable place in the ancient Sagas of Icelanders. We first anchored in the hurricane-hole bay of Elliðaey Island, a refuge for colorful tufted puffins and Arctic terns. Then, the next day was a short hop to Stykkishólmur, a large and charming fishing town—but a little too popular, with tour buses clogging the streets.

Continuing down the coast, we stopped in Grundarfjörður, widely known both for its photogenic Kirkjufell, or Church Mountain, and legendary summer-solstice party. The crew of Katya, who stumbled into the party by chance on their way south, later confirmed that modern-day Vikings live up to their reputations as friendly and wild party animals.

Our last stop before returning to Reykjavik was a second visit to Ólafsvík, where we discovered the challenges of refueling in Iceland. There are two main fuel companies that provide dockside diesel in Iceland using all-automated pumps. The pumps have red and green covers denoting the brand of diesel, not fuel type (gasoline is rare at the dock). To use one, you must have a proprietary charge card and code to pump your own fuel.

Our experience turned into a classic example of cascading bad luck and a mistake: We arrived on a falling tide, and the only pump we could use was in very shallow water. Our depth alarm wouldn’t shut up, so we couldn’t wait, and besides, the card we had wouldn’t work. And, of course, human help did not exist. Our mistake? Our calculations of fuel reserve turned out to be based on a bigger tank than we actually had. The next day, in dead calm and within sight of Reykjavik, the engine sputtered out.

Despite the embarrassment of having our grand adventure end with a tow back into the harbor, our bareboat expedition in Iceland was a huge success and a lot of fun. No, it might not be a warm cruise around a sunny lake, but for the right crew, it’s a wonderful experience.

Stephen Blakely sails Bearboat, his Island Packet 26, on Chesapeake Bay.

Resources for the Journey

Iceland Yacht Charter: The company has five bareboat charter vessels available, four Bavaria sailboats, ranging from 37 to 50 feet, and an Arvor 215 power cabin cruiser. They are docked behind Reykjavik’s famous concert hall, the Harpa. A licensed captain is required to charter. Boats come with a good chart plotter at the helm and paper charts, but bring tablet or phone navigation as backup. Our Bavaria 50s were fully capable and comfortable even in the worst weather; as with any charter boat, check out your boat thoroughly during the briefing. Cruising season is June through early September. We were their first American customers.

Cruising guide: Arctic and Northern Waters, including Faeroe, Iceland and Greenland, by Andrew Wells, RCC Pilotage Foundation. Written by hardcore cold-weather sailors, it has a wealth of useful (and sometimes intimidating) information about Arctic cruising.

Currents and tides: The northerly flowing Irminger Current prevails in western Iceland, and is a branch of the North American Drift. Tidal currents run clockwise around Iceland starting in the southwest and are strongest on the west coast, usually running 1 to 3 knots but able to hit 5 to 7 knots in narrows and off headlands.

Weather forecasts: Reykjavik Radio broadcasts forecasts in English throughout the day. Iceland is one of the most wired countries in Europe, so Wi-Fi internet connections and forecasts were available in all but the most remote areas. Online wind apps were extremely helpful.

Radio and safety: The Icelandic government has only three Coast Guard ships, dedicated mostly to buoy maintenance (and there aren’t many). If you get in trouble, you will depend on the Icelandic Association for Search and Rescue, run by volunteers and funded by donations and contributions from the fishing industry. ICE-SAR has stations around the country, uses a fleet of old British lifeboats and, as does the US Coast Guard, monitors VHF radio Channel 16. In extremely remote areas blocked by sharp fjord walls, neither VHF nor cellphones might work. Virtually all boats have AIS, and the fishing fleet will clutter your chart-plotter screen.

Harbors: Contact the local harbormaster when you arrive; some charged us a fee, some did not, but all were friendly and helpful. Potable water is routinely available; electricity rarely is. Go to the public pools for showers. Outside Reykjavik, there were no marinas, and in the remote waterfront areas we visited, public toilets were nonexistent; you will often need to hunt for an unlocked commercial bin to dispose of your garbage. Larger towns have Bonus or Kronan grocery stores, but reprovisioning in rural areas can be difficult. Chandleries do not exist outside Reykjavik.

What to Expect

Prices are high in Iceland, especially for food and alcohol. A $15 bottle of Beefeaters gin in the US was $30 in the duty-free store in Keflavik Airport and $60 in the Vinbudin state-run liquor stores. We found that these stores have irregular hours and can be hard to catch while open.

The country’s environmental record is mixed. Eighty percent of Iceland’s energy is produced by clean geothermal or hydropower sources, yet Iceland is the only country that allows hunting of endangered puffins and one of the few that still permits whaling. There is only one company in Iceland that hunts whales but many that run tourist whale-watching trips. Icelanders note that only tourists tend to eat whale meat.

And while Iceland is famous for its world-class cooking, it’s also infamous for its winter food festival that serves up such historically accurate (and to me, vile) ancient Viking dishes as fermented shark. Chef, author and travel journalist Anthony Bourdain, in his No Reservations segment on Iceland, was one of the few reporters to explain why: “They serve only Greenland shark, a unique and rare fish that excretes its waste through the skin, making the meat both toxic and foul. Only after fermenting in the ground for six months does it become safe to eat—and the Vikings were willing to wait.” When he tasted the dish, Bourdain pronounced it “the single worst thing I’ve ever put in my mouth.” For someone who made a career of traveling all over the world seeking out weird, gross and disgusting things to eat, Iceland ranked No. 1.