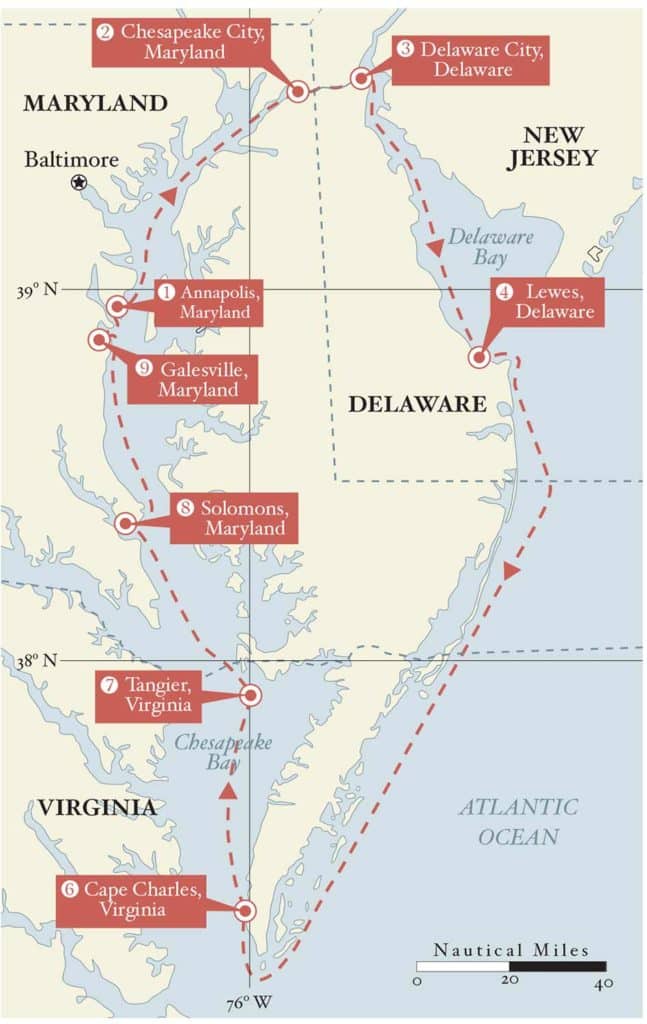

Every spring, the US Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland, sends out dozens of plebes on its beautiful dark-blue Navy 44 sloops to do a “Delmarva”—a circumnavigation of the shrimp-shaped peninsula that divides Chesapeake and Delaware bays, and is shared by Delaware, Maryland and Virginia.

This 400-or-so-mile circuit covers the entire length of both bays and includes a 150-mile offshore passage between the two, a “little loop” that the Navy sails nonstop in about three days. The route offers round-the-clock training exercises in leadership and command, boat systems, navigation, safety-at-sea, and watch-standing protocols in all kinds of weather.

Local sailors like this challenge too. Since fun should be part of the journey, I took a leisurely 10 days to sail the Delmarva in my own boat, a 1983 Island Packet 26 named Bearboat, which gave my two crewmembers and me time to explore some wonderful places along the way. We started in early May, just a week before the Academy flotilla set sail in what they dub the “Fogmarva,” due to the risk of fog this time of year.

As the Navy recognizes, this is a serious journey for any sailor, with plenty of big-enough water. Our voyage coincided with the onset of a Greenland Block—a stalled northern high-pressure system that pushes the jet stream south and blankets the East Coast with strong, cold Canadian air. We had gale- or near-gale-force winds for well over half the trip, initially from the south. The howling wind and long fetch straight up the Chesapeake produced some of the biggest waves I’ve encountered on the bay: 5 feet with short wave periods, which is a lot for the narrow northern section.

Delaware Bay is often a tough slog too; the route is long enough to ensure opposing wind and tide, much of it in restricted waters. It’s generally quite shallow and has lots of big commercial-shipping traffic. Unlike Chesapeake Bay, it has rocks and almost no harbors of refuge. To our surprise, the open ocean turned out to be the smoothest part of the entire trip.

This was the second Delmarva I’ve done in Bearboat, which had just received several major repairs and upgrades. Most important were a rebuilt diesel and quick-setting single-line reefing system because we sailed under single or double reef almost all the time.

As I did on my first Delmarva, I sailed the loop clockwise to take maximum advantage of the west-to-southwest prevailing winds. I prefer to go in May to avoid late-winter cold fronts and early-summer heat waves. Because my boat does not have radar, I timed the overnight coastal passage to the full moon to take advantage of the light. Two crew came along: Mike Koleda, former owner of a wooden lobster boat, and Mark Burosh, an ex-Marine and now a professional fly-fishing guide with commercial marine experience.

Aptly enough, since Bearboat’s home port is Galesville, Maryland, we cast off in a gale. Our first day was just a two-hour sail north to Annapolis because the morning was spent with final packing and a thorough boat briefing.

The storm had canceled a big sailboat race out of Annapolis that day, so we had lots of room to tie up inside Ego Alley, downtown’s famous and usually crowded narrow harbor inlet. Rain, strong southerlies and a near-full moon had flooded the banks. A flotilla of ducks paddled over the submerged harborside parking lot. Because Mark had never seen Annapolis, we set off to explore the US Naval Academy’s campus—especially Bancroft Hall (with 33 acres of floor space, it’s the largest dormitory in the world) and the Academy’s fleet of Navy 44s docked in the sailing basin.

Breakfast was at Chick and Ruth’s Delly, the oldest eatery in the historic district, a palace among greasy spoons, and a magnet for local color. Afterward we suited up in our foulies and motored out into a southeast gale. It was a daylong roller-coaster ride up the bay under heavily reefed sails.

In between squalls, we passed under the soaring double spans of the Chesapeake Bay Bridge, and watched the smokestacks and office towers of Baltimore pass by to port up the Patapsco River.

As I said on my first Delmarva, I sailed the loop clockwise to the advantage of the west-to-southwest prevailing winds.

Chesapeake Bay narrows as you go north, forcing recreational boats into the deep commercial shipping lane that hugs the Eastern Shore. Just past Poole’s Island, the channel tightens and bears northeast, which put us in the lee of the Eastern Shore, settling the ride a bit. By midafternoon we entered the Chesapeake and Delaware Canal, the northern boundary of the Delmarva Peninsula, and were soon tied up at the Chesapeake City town dock, tired but happy that both boat and crew had passed a tough early test.

My little Island Packet is a strongly built boat, and—properly handled—loves a gale, but these conditions were a bit unsettling to Koleda at first. “When I was at the helm looking up at the wave crests going by, I was starting to wonder what we were doing out there,” he said later over a beer. He’d get used to heavy weather.

The C&D Canal is a 14-mile-long sea-level connection between Chesapeake and Delaware bays and one of the busiest waterways in the nation, carrying about 40 percent of the commercial marine traffic to and from Baltimore. It can be a dangerous place: Currents are deceptively strong, fog will shut it down, and various fatal accidents have occurred here over the years.

We left early the next day, motoring under several bridges and pushed along by a cold westerly near-gale. The canal exits to the grim industrial landscape of the Delaware River: Boiling clouds of steam gush from the hulking Salem nuclear power plant on the far shore. Huge pylons and power lines snake across the water, and refineries dominate the shoreline upstream. Turning north, we motored through yet another rain squall to the nearby entrance of Delaware City and the long floating dock of the town’s marina.

We had come to visit Pea Patch Island and Fort Delaware State Park, a little-known Civil War-era fort and prison in the middle of the Delaware River. Just half a mile offshore, the fort is in surprisingly good condition and has excellent displays of what life was like there. The fort held more than 40,000 Confederate prisoners of war (including almost all Southern troops captured at Gettysburg), and is well worth a visit.

We cast off at dawn the next day—our first without rain—and began winding our way down Delaware Bay, edging just outside the buoys to dodge the occasional gasoline barge, container ship or liquefied-natural-gas tanker.

A somewhat dicey passage begins in Delaware Bay below the nuclear plant: The channel narrows sharply along rocky ledges, marked by the Ship John Shoal and Elbow of the Cross Ledge lighthouses. It can be a tight squeeze—Elbow light was hit by ships so many times, its keepers slept in life jackets.

Almost all outbound private boats head for Cape May, the northern entrance to Delaware Bay, but we were going to the smaller town of Lewes (pronounced LEW-iss) and Cape Henlopen on the southern shore. The town’s narrow harbor is reached via the Lewes and Rehoboth Canal, and its gateway can’t be missed: A huge wind turbine marks the spot. A sharp turn to port on entering takes you down a long channel to the harbor, with an immaculate town marina and park on the south side next to the bright-red Lightship Overfalls museum. The town’s small but charming historic district, just two blocks from the dock, has wonderful architecture, great shops and excellent restaurants.

The next morning, as another storm blew in, we headed north toward an even more isolated part of the day: Tangier Island.

Early the next morning—our first clear and dry day— Koleda reprovisioned the boat while Burosh and I rented bikes to explore nearby Cape Henlopen State Park. This area was Fort Miles artillery base during World War II, part of the coastal-defense system. Today, the park offers 6 miles of pristine Atlantic beaches, nature trails and campgrounds, Army barracks and artillery displays, and an original observation tower you can climb.

By noon we returned to the boat, topped off the tanks at Lewes Harbor Marina, and headed back out to sea. Riding a peak ebb tide before a crisp northwest wind, we flew around the tip of Cape Henlopen, bound for Chesapeake Bay.

On my first Delmarva, I kept about 10 miles offshore on this leg, but this time followed the charted 3-mile line down the coast. This was the day the Greenland Block finally dissolved, and as the wind clocked lightly ahead, we rolled up the genoa and chugged comfortably down the shoreline in gentle 2-foot seas. For trips like this, I cook up one-dish meals that are vacuum-bagged and frozen, then simply reheated in a pot of boiling water. Just as the fading sun slipped into an orange horizon, a fat, full and stunningly white moon rose to port. We celebrated with a delicious hot stir-fry.

It’s always magical being at sea in the moonlight, and for me, it’s a rare privilege to bear witness to the slow passage of a complete celestial night. The moon, with bright Jupiter just to the west, provided easy headings to follow as they slowly arced across Bearboat’s bow and rigging. There was little traffic during our cold four-hour shifts, and the off watch below was rocked softly to sleep by soothing Atlantic swells.

At dawn the next day, approaching the distinctive skeleton tower of Cape Charles Light at the northern entrance to Chesapeake Bay, we were greeted with a surprise—in the shimmering early-morning sunlight there was a sudden, confusing appearance of a strange-looking orange-and-white freighter ahead. It turned out to be an optical illusion, showing a much-distorted entrance to the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel just over the horizon.

We re-entered Chesapeake Bay through the North Channel span of the Bay Bridge-Tunnel, a convenient passage for boats with less than 75 feet of air draft. This allowed us to quickly round the cape and make landfall at Cape Charles City, just up the Eastern Shore.

Cape Charles City was the once-prosperous railhead for all ferryboat traffic between the tip of the Delmarva Peninsula and Norfolk, Virginia. It was bypassed when the 23-mile-long Bay Bridge-Tunnel opened in 1964. It’s still a bit of a ghost town (especially the rusting railyard) but is slowly coming back. For cruisers, the main attractions are Cape Charles Yacht Center and Kelly’s Gingernut Pub, set in a beautifully restored old bank.

The next morning, as another storm blew in, we headed north toward an even more isolated part of the bay: Tangier Island, the last inhabited offshore island in Virginia. This hardworking community of watermen descends from original settlers from Cornwall in the 1770s, and residents still speak in a unique “orphan dialect” of British and Southern accents. This small, deeply religious community is fighting to survive: With high ground only 4 feet above water and flooding increasingly common, scientists say the entire island is destined to be lost to rising sea levels.

Early the next morning, we set off on a long northwesterly passage toward the Western Shore. This route took us past Smith Island (Maryland’s last inhabited offshore island) and the Hannibal—the last live-fire target ship on the Chesapeake, scuttled on a sandbar and riddled by Navy aircraft.

Late that afternoon, we entered the Patuxent River, watching jets and helicopters buzz around the massive Naval air base on the south side of the waterway. On the north side is the narrow entrance to Solomon’s Island, an excellent hurricane hole, home to some of the best marinas on the Chesapeake and one of the top cruising destinations midbay. Just as we arrived, a strong northerly windstorm set in, delaying our final run for home.

When the blow passed, we started the last 40-mile leg due north up the midbay. This route has some interesting landmarks: Cove Point Lighthouse, the huge Cove Point LNG dock, Calvert Cliffs nuclear plant and a Navy radar base. This is a popular stretch for striper and perch fishing, so we had to dodge lots of charter boats. By midafternoon, we reentered the West River and backed into Bearboat’s slip in Galesville, safely closing the loop.

A circumnavigation of the Delmarva peninsula has plenty to offer sailors. As the Navy knows, it’s a serious test of seamanship; for cruisers, it’s a challenging circuit you can do in a week or so. And it’s a great way to explore one of the nation’s best cruising grounds and meet some wonderful people—such as the funny-but-tough-as-nails waitresses at Chick and Ruth’s; Tim Konkus, the incredibly helpful owner of Delaware City Marina, who gave his storm-stranded mariners an excellent weather briefing; and Milton Parks, the owner of Tangier Island’s Parks Marina, and a legendary retired waterman.

But perhaps the best parts are being able to go for a long sail in varied conditions; putting the boat, skipper and crew to the test; and making “local” a bigger place.

Based in Washington, D.C., Stephen Blakely sails his Island Packet 26, Bearboat, throughout the mid-Atlantic coast.