We should do something,” my wife, Carolyn, said. “Something special.”

Carolyn is still a party gal. She loves to invite fellow sailors aboard our 43-foot Wauquiez ketch Ganesh or visit on their boats, or even go ashore to mingle with the dirt dwellers. She is far more social than me.

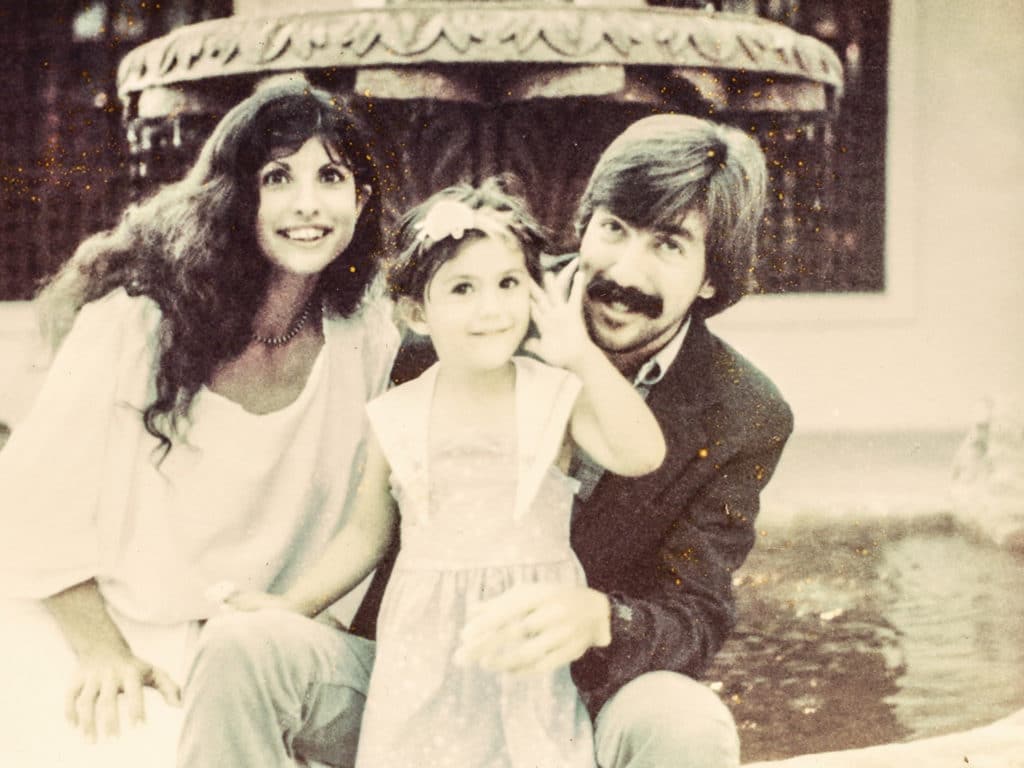

“You mean for our 50th?” I asked. She came aboard my boat in 1968 to sew up my curtains, and has been stitching happiness into my life ever since. We were both 15 years old at the time and, being a gentleman, I waited until she turned 16 to suggest we run away to sea together.

Sadly, she wanted to complete high school first. “How middle class,” I had sniffed at the time.

However, patience is a sailor’s virtue.

At age 18, fresh from giving her valedictorian speech at Chicago’s Gage Park High, she stepped aboard my wooden double-ender and said, “Show me the world, skipper.”

I’ve been doing my best ever since.

“Sure,” I said to her, resurfacing into current reality. “I’m up for anything on our golden anniversary.”

“Actually, I was thinking of your 60th anniversary of living aboard,” she said. “Lots of married couples are still together after 50 years; very few sailors are on their sixth decade of sailing.”

I’d never thought of it that way. I hadn’t set out to achieve a liveaboard record, merely to have the highest-quality life I could imagine, and share it with the woman I love.

My earliest memories are of growing up aboard the 52-foot Alden schooner Elizabeth—and of the shock of my parents selling her and moving ashore when I was 12. It didn’t take long for me to realize that dirt dwelling wasn’t for me. So at 15, I purchased the double-ender Corina, sans engine and rig, said goodbye to formal education, and was cruising the Great Lakes a year later. So what if Corina was so rotten that the only thing keeping her together were the roaches holding hands? Such freedom, once tasted, is forever desired.

Looking back, I think it’s fair to say I’ve seen some changes around the waterfront. Here’s an example: Elizabeth had one small 12-volt battery; aboard Ganesh, we have 12 large deep-cycle batteries.

When I was still a kid, my father wanted me to ensure I’d have some change in my purse, so he taught me celestial navigation and Morse code so I’d always be able to earn my living. Ahem! How time marches on.

The schooner I grew up on was built of wood. Caulking kept out the water (well, some of it). My childhood home had more leaks than the White House. To empty the bilge, we used a bronze barrel pump mounted in the cockpit while at anchor and a large deck-mounted pitcher pump at sea. The pitcher pump’s handle was over 6 feet long. My mother hated it, especially while pumping it for four hours to keep our home afloat while Father and I were ashore.

Elizabeth’s anchor rode was tarred hemp, and hauling on it was like grabbing a fistful of fishhooks. Our rigging was galvanized steel—spliced, of course. Both running and cabin lights were primarily kerosene. We had two instruments aboard: temperature and oil-pressure gauges for our tiny gasoline Scripts auxiliary, an engine that ran whenever it felt like it.

Our sails were made of Egyptian cotton, and fit with mast hoops that made for both a quick drop and an easy climb. All our deck and rigging hardware was silicone bronze; stainless steel (which is totally misnamed) hadn’t been perpetrated on the marine community yet.

Our galley stove was made by Shipmate and coal-fired (unless we were short on money and forced to feed it wood). Little Liz, our wooden 10-foot dinghy, was clinker-built, and we sculled her. Our compass was regularly swung, we had its deviation table and, yes, we knew the local variation as well.

Since Elizabeth had been built to sail and race in the Great Lakes, both her 100-gallon riveted-iron water tanks had underwater valves to let in the fresh water. Our marine radio transmitted 20 watts of amplitude-modulated power, was crystal-controlled, and (pretty much) would reach any vessel we could see with our naked eye.

To determine our depth, we used a lead line marked in fathoms and armed with wax so that we’d get a sample of the bottom as well. There was a trick to tossing it forward from the bowsprit if you wanted an accurate, vertical double-tap on the bottom. Rock felt different than sand, and sand felt different than mud.

Yeah, it was different back in the day.

Marinas didn’t exist, aside from major cities, so usually we’d just raft up alongside a tug or fishing vessel. We couldn’t tell people we were cruising; that didn’t make sense back then. So we’d tell them we were delivering the boat or collecting tropical fish—anything to disguise the fact that my father needed a timeout from Western society. Whenever he heard the word “civilization,” he’d shout: “Sounds like a damn fine idea to me. We’ll return if it happens.”

Oh, it was a wonderfully wild and wacko childhood. The only difference between me and Tom Sawyer was that nobody forced this sailor into school or church. Thank you, Lord!

Once, a movie producer attempted to charter Elizabeth for an upcoming flick but had a tough time dealing with my beatnik father. Just because we were dead broke didn’t mean the old man lacked integrity.

“What, I look like a bus driver to you?” he asked the producer.

A few days later, a shifty-eyed fellow showed up and said he had to get out of town quick.

“Skipping bail?” my father mused.

“That’s right,” the man said with a shrug.

“Are you guilty?” my father asked.

“Guiltier than a nun with a dildo,” the man replied.

“Welcome aboard,” my father said.

Oh, what a collection of seagoing misfits slept on deck in various ports. There was a circus guy named Ruby the Red, who had dropped his trapeze-swinging brother; an alcoholic undertaker who used to brag about burying his mistakes; an ex-cop who had run away to sea after tasting the oil from his gun’s barrel. Oh, and Barefoot Benny, a lawyer from Natchez, who had thrown his shoes at the judge while screaming, “No, the obscenity in this courtroom is your honor, Your Honor.” And there I was, swinging through the rig above it all, drinking it all in.

Nobody had any money. The last time I’d seen anything bigger than a $5 bill was when we’d paid $100 for Elizabeth—or whatever was at the end of those stiff dock lines leading like iron bars into the dark, swirling water. Yes, boats underwater tend to be cheap, and being underwater wasn’t so unusual back then.

In the Caribbean, on islands such as Tortola, all the local boats would take on a load of rocks, and then sit out in Road Harbour to await a hurricane. If the barometer continued to drop, skippers waited for the gale to start, then knocked out the garboard plugs, and swam ashore. Once the storm had passed, those West Indians would dive down, toss out the rocks, watch their wooden boats rise to the surface, pound back in the garboard plugs, bail, and they were good to go. Try that with a boat brimming with computer equipment, a bilge full of engines, and a cockpit dotted with multipixel screens.

Nobody viewed us as profit centers when we sailed into a port in the 1950s. Hell, it was more likely the townsfolk would take up a collection! One of the reasons we loved to raft up with fishing boats was that often the fishermen would bring over a red snapper, my mother would cook it up, and we’d all get to telling stories while the rum bottle circumnavigated.

Stories! The stories were all we had. They were the universal entertainment of the salt-stained poor. We were flotsam and jetsam, all of us. The most respected fisherman in the harbor wasn’t the one who caught the most fish; it was the guy who told the best stories. These men were clever and violent gunslingers of harsh words and tall tales and dangerous fishing yarns—and don’t think I didn’t listen. I listened hard. These men were my heroes; they were everything I wanted to be—then and now. I used to know how much to trust a man by looking at his hands to count the calluses. I recall how my father used to say, “If it can’t be fixed, don’t bring it aboard.”

All of a sudden, I realized that I couldn’t tell if I had spoken that last part aloud or not. So I again swam upward from my reverie into current reality, and stared across the galley table at Carolyn.

“Boy,” she said. “You’re sounding like an old fart now.”

“I’m 68,” I said. “If I’d had any idea I’d get this old, I would not have done half the stuff I did, leastwise not in those dosages.”

“Getting back to the point,” Carolyn said, “what do you want to do that’s special?”

We were in Batam, Indonesia, at the time. It’s not a bad port, actually.

“How ’bout we take a ferry to Singapore?” I suggested.

Carolyn slapped herself on the forehead.

“Let me get this straight,” she grimaced. “To celebrate 60 years of living aboard, you want to take a boat ride?”

“And 50 years of wedded bliss too,” I added. “We’ll go see our daughter and our grandkids in Singapore. I can handle a little rock hugging, if you do your part.”

“You mean shake your bed and sprinkle drops of water on you so you can get to sleep?” Carolyn quipped.

“Is that too much to ask?”

“The things I do for love,” she said with a smile.

The Goodlanders packed a fair amount of sailing into the past few months and are now enjoying their latest landfall: Singapore.