It’s a typical down-on-the-dock scene in Maine. A handful of old-timers who have cruised this coast for better than a half-century share stories about favorite anchorages, shoreside hikes and precious swimming quarries. For them, the islands of Maine make life worth living, and the chance to sail among them summer after summer has more than justified the annual expense and effort they put into maintaining their sailboats. And then along comes Steve Stone and Amy Tunney, relative newcomers to town. Each is carrying a dry bag and wearing a backpack in preparation for a camp-cruising voyage down Blue Hill Bay. Once out in the open water, they’ll make a final assessment of the wind forecast over the coming days, and they’ll ease off toward Acadia National Park to port, or toward Merchant Row and Vinalhaven to starboard.

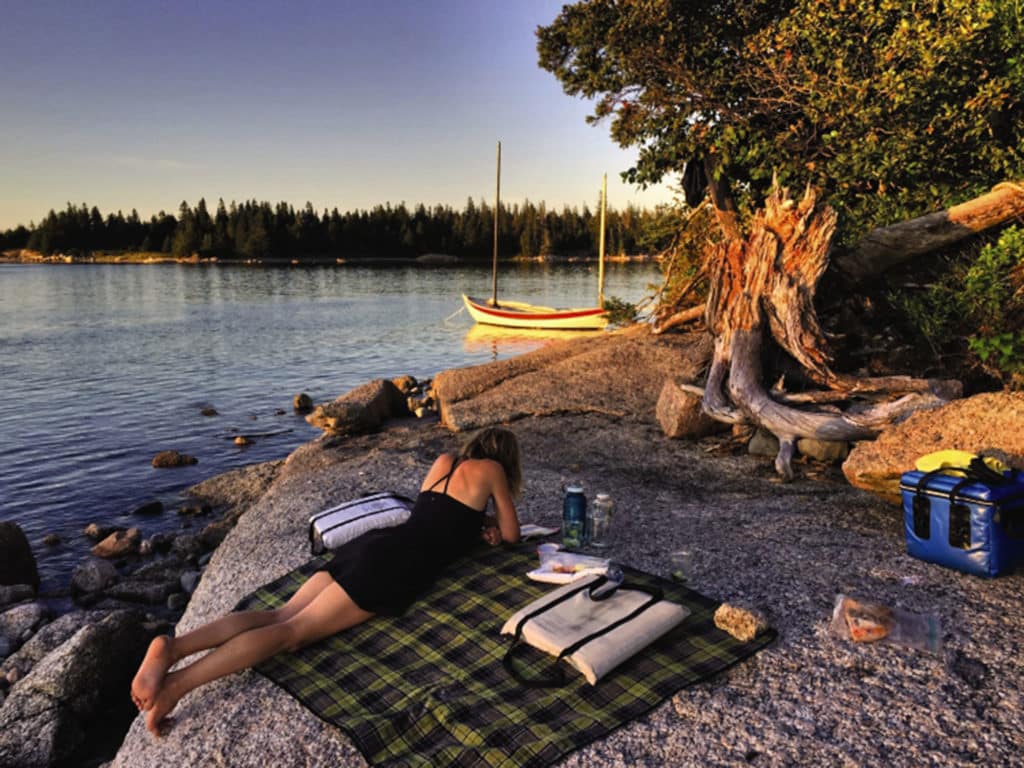

Instead of spending countless hours sanding and painting and caulking their wooden boats as the purists do, Stone simply pulls the cover off their elegant craft, Howdy, slips it off the trailer into the water, and it’s good to go. No big hydraulic trailer necessary, no knuckle-busting engine work, no masts to step with a crane. When the wind blows, he and Tunney sail. When the wind quits, they row. Naturally the old-timers want to know more about how they go about the camp-cruising thing they have going.

Well, first of all, Stone and Tunney chose the right boat and boatbuilder: an Iain Oughtred-designed Caledonia Yawl built by Geoff Kerr. Kerr has built more than 20 boats to this design using marine-grade okoume plywood and epoxy, both of which are light and strong. And because the wood doesn’t shrink and swell like traditional sawn lumber, they can be stored on a trailer in a hot garage or under a tarp and be ready to launch at a moment’s notice without danger of leaking.

Summer by summer, they have added to their gear, with each piece of kit providing a sweet balance of simplicity, portability and comfort.

Besides this, Caledonias are great sailing boats: stiff in a breeze, easily reefable and surprisingly fast even to windward. A virtual ballerina of a boat at the hands of skilled sailors, these yawls are always in balance as they roll along before a freshening sea breeze on a summer afternoon.

At 19 feet, 6 inches, with a 6-foot-5-inch beam, Caledonia Yawls can carry a lot of gear and still have room for people. Occasionally we have even seen as many as 10 aboard Howdy with Stone and Tunney—plus a couple of dogs—enjoying an evening margarita cruise. With a draft of only 11 inches with the centerboard up and a sturdy keel, Stone can haul their Caledonia up the beach or pull it into deeper water with a haul-off anchoring system.

So how do they find big quantities of summer enjoyment in a small craft?

Besides choosing the right boat to carry them on their sail-camping adventures, Tunney and Stone have amassed gear and equipment to ensure that while they might be camping, they definitely aren’t roughing it. First off, they insisted on comfortable bedding. For this they chose a couple of Therm-a-Rest NeoAir inflatable mattresses. Rolled up, each one measures 4-by-6 inches, so onboard stowage is no problem.

And this was only the beginning. Summer by summer, they have added to their gear, all of it a sweet balance of simplicity, portability and comfort. Stone says their go-to website for discovering the best in camping apparatus is outdoorgearlab.com.

Another thing they make sure they do is carry ample fresh water, not only for drinking and cooking, but also for showers. What they take adds up to something like a gallon per day per person, plus fresh water for their hang-in-a-tree sun showers from Hydrapak. Water is heavy and takes up valuable space in the boat, but to stay fresh and clean on a five-night trip seems well worth it to them. As the water gets used, the bags roll up to the size of a tennis ball and stow away.

There’s only one real menace along the Maine coast, but it’s so reliable, you can set your clock to its irritation: mosquitoes. The only defense is to wall them off; set up the tent early and then dive in as soon as the first mosquito appears. Naturally they bring along bug dope, but they resist a total DEET soak-down if at all possible. Their other defense is to avoid islands with intense mosquito problems: islands with standing fresh water or adjacent salt marshes. Setting up camp on the windward side of an island also helps. And camp-cruisers generally stay clear of islands with rocky beaches. They make for hard landings, and swarms of biting flies often lurk beneath the stones. Once when Tunney and Stone veered off course to an unscouted island too late in the day to find an alternate site, Stone recalls that his partner came under a ferocious attack of these biting flies as she scouted out potential tent spots ashore while he rowed along the cobblestone beach waiting for her signal to land and unload. Seeing her slapping and cursing as she strode through the high grass, he pulled ashore and threw her a can of bug spray. Vigorously scrubbing chemicals into her thick hair and coming up with a total grin at the situation, this otherwise chemical-averse woman showed him that camping-wise, she was signed up for the long haul.

RELATED: A Celebration of Boats in Maine

Besides a tent and comfortable bedding, they carry headlamps, a good Whisperlite white-gas stove, super-insulated soft coolers to keep food fresh and ice cubes at the ready for the daily margarita, a grate for campfire grilling, and a horse-feed-style rubber bucket with a rope handle. The bucket, they say, is good for chores and fire safety. Anything needing to stay dry goes in large dry bags. True, it’s a lot to lug, but that’s what it takes to make their life comfortable—a priority of their own choosing.

For food, Tunney does the planning. She puts together meals before they go, such as a vegetable hash with chicken, frozen pizza from their favorite pizzeria that they grill by the slice over a charcoal fire, or veggie burgers. What the meals have in common is that they are easy to transport and simple to prepare.

But what ties it all together is the beauty and accessibility of the Maine coast. Not only are there countless islands to camp on within easy reach along the midcoast, the islands are generally strung out in a way that makes four- to five-day trips work for them.

When summer weekends arrive, they cross-reference wind and weather apps on their phones to get a feel for upcoming conditions. No matter what they have laid out in theory, it’s the weather that will shape their actual trip. This means the starting point isn’t usually chosen until the day before the launch, and the specific route they end up taking through the islands develops as they go. They always have a rough plan, usually with a specific island in mind for the evening, and Stone draws upon his old flight training to keep one eye on the weather for storms as well as a stream of bailout islands and coves as “emergency landing strips” along the way.

A key part of the Down East camp-sailing planning process is finding a safe place to bring the boat ashore or anchor it off with a haul-out system. Given the 9- to 12-foot tides, using an anchor and line and hauling the boat out past the low-tide line often means anchoring the boat 100 or more feet from shore. Getting things right is essential to a good night’s sleep. The last thing campers want is to find themselves wading out in the middle of the night if bad weather blows up.

What ties it all together is the beauty and accessibility of the Maine coast. Not only are there countless islands to camp on within easy reach along the midcoast, the islands are generally strung out in a way that makes four- to five-day trips work for them.

Like sailing itself, sail-camping is a learn-as-you-go experience. And both Stone and Tunney have found it to be an economical and enjoyable way to experience one of the most beautiful, safe and accessible coastlines in the world. In summer, winds are generally manageable and predicted with great accuracy on phone apps and National Weather Service VHF-radio broadcasts. Navigation, once a challenge, has been made simple by GPS-enabled smartphones and other portable devices. Although they prefer charts and a compass, they use Navionics on their iPhones as a backup. A great many, perhaps even a majority of Maine islands, are located in waters protected from the open sea.

The reward for all that’s involved in small-boat adventures? “Cruising without an engine, with only oar and sail power, releases the tension from sticking to some plan,” Stone says. “If we follow the wind and currents each day, there’s no hard plan that requires sticking to. We often speak of ‘going with the flow’ and being forced to be in the moment. Without an engine, self-reliance becomes a necessity, and self-reliance usually brings peace and independence.”

Ultimately it is this peace and independence, enmeshed as it is in the challenges of exploring the natural world of Maine’s beautiful islands, that make Tunney and Stone love their getaways so deeply and brings them ever closer as a couple.

Bill Mayher is a writer and sailor who hails from Brooklin, Maine. He and Steve Stone are co-founders of marine video site offcenterharbor.com.

Get to Know the Islands

To better familiarize themselves with the geography of potential camping spots, Amy Tunney and Steve Stone often take time to scope out potential islands to camp on, dipping into coves and up creeks to see what might work on a future voyage. Luckily a great many potential camping islands are under the auspices of either the Maine Island Trail Association or the Maine Coast Heritage Trust.

MITA has arranged permission from over 200 island owners to allow access to the association’s members. Many allow overnight camping. In exchange, MITA runs spring and fall cleanup programs and generally keeps a close eye on things. Accordingly, island owners have come to value their relationship with MITA, and the number of islands designated for camping has increased over the years. For beach cruisers, the best reason to join the association might be to get a copy of its guidebook and be able to access its app by smartphone. The book makes for great bedside reading and dreaming in the offseason, while the phone app is particularly useful during the cruise itself.

Both the book and the app are arranged geographically and give a convenient regional overview. Additionally, there is a chart of each MITA island that points out landing places, informs campers about various regulations that might apply, and shows the locations of campsites. MITA is vehement about the latter. The last thing they want is campers roaming around on an island with hatchet and bow saw, whacking out additional campsites. If the guide indicates one tent site on a given island, that’s it—one campsite. Faced with such limitations, camp cruisers are advised to get going early to their next landfall so they can be sure to get what they want, particularly on summer weekends.

The Maine Coast Heritage Trust, according to its mission statement, “conserves and stewards Maine’s coastal land and islands for their renowned scenic beauty, ecological value, outdoor recreational opportunities, and contribution to community [well-being].” So far the trust has conserved 154,150 acres, protected 320 islands and established some 93 preserves featuring 93 miles of trails. Without question, the coast would look far different without both the efforts of the trust and the generosity of coastal land owners who have donated land in order to keep it the way it was when they found it.