Our first warning was the stillness. You might find it cliche that, as sailors, a calm morning would spell ominous weather on the horizon. But we were at the bottom of the world—Puerto Williams, Chile—and we were about to make a run for Cape Horn.

We’d arrived in Puerto Williams on Christmas Eve, having sailed a year and a half to get there. Our 36-foot sloop was warped, weary and falling to bits after battling a barrage of storms along the coast of Patagonia. We ourselves were beaten and fatigued. But we had a window, and we didn’t know if another would come for weeks, or even months.

Cape Horn, South America, is where the Pacific and Atlantic oceans collide. Waves have been recorded at over 100 feet high—the size of a 10-story building—with winds frequently reaching hurricane force. The rock itself withstands a siege of low-pressure systems year-round. These storms originate in Antarctica, work their way north across the Southern Ocean, and then slam through the passage between Cape Horn and the Antarctic Peninsula. The size and intensity of these storms—and the steepness of waves off Chile’s continental shelf—are enough to break any boat. But these systems also follow each other in such close succession that each storm barely has time to clear the passage before the next is closing in.

The conditions ahead, however, looked almost perfect. It was December, and summer had begun its brief visit to the bottom of the world. The low-pressure system currently sweeping around the Horn promised to leave a vacuum in its wake, while the following storm was poised to miss its mark, making landfall farther north up the coastline of Patagonia. The ensuing conditions were supposed to leave the Drake Passage clear of western winds for a whopping three days.

Perfect.

We wanted badly for a break in our misfortune. After overcoming a survival storm way back in the Gulf of Mexico at the outset of this journey, it had become a running joke that when we finally arrived at Cape Horn, the ocean would be glassy-calm. We didn’t want the shirtless, smooth-sailing conditions that we’d been robbed of in the Caribbean; we just wanted a window. After all that we’d overcome to get to there—hurricanes, pirates, bureaucracies, starvation, even each other—it seemed fair (if not overdue). We thought that we had earned it.

Our forecast was promising. Some of the local expedition boats were making their first run to Antarctica for the season. Plus we had a community of sailors, military veterans and civilians cheering us on from the sidelines. But even as we cast off our lines and began motoring down the Beagle Channel, something felt wrong. Icy water rolled out in a viscous wake behind us. The sun rose low over the mountains surrounding the channel. None of us spoke. I could see it in my shipmates: Taylor’s grip on the helm, and the way John’s back stiffened at every minute sound. The stakes were too high. Besides, there was a trend that had plagued our journey from the first leg—that a serene start always preceded a tumultuous end—and our key takeaway from the Furious 50s was that, at the bottom of the world, calm seas come at a price.

We were desperate for a handout—an easy sail around the world’s most treacherous waters—but Cape Horn didn’t care what we’d endured to get there. You pay a toll when crossing what some of our predecessors had nicknamed “the sailor’s graveyard.” Almost everyone pays it. We weren’t about to get a free pass.

Even if the tale that had brought us here, and the motivation for it, was almost too hard to grasp or believe.

Three years earlier, Taylor Grieger and I were lounging on a beach in Guam. Rounding Cape Horn certainly wasn’t on our radars. In fact, sailing anywhere particularly remote wasn’t on mine. I’d flown to Guam from Scotland as a student to conduct interviews with female helicopter pilots in the Navy. Taylor, meanwhile, was wrapping up six years as a Navy rescue swimmer. His four-year stint on Guam had left him with an outstanding record of rescues…and a belly full of bitterness.

Guam was the first time we had seen each other in eight years. Taylor had gone into the military after high school, while I’d taken the academic route. Despite polar-opposite pipelines, we were able to pick up right where we’d left off: as buddies, and former teammates on the varsity swim team.

It quickly became apparent, though, that Taylor’s time as a rescue swimmer was far from the hero’s journey he’d been promised, or originally envisioned. His motivation had been to help people on maybe the worst day of their lives, and yet he found himself constantly training for combat. The pace on Guam was equally ruthless. It wasn’t unusual to have back-to-back flights scheduled, barely giving time for Taylor to stretch his legs before beginning the next mission. Their position off Mariana Trench, meanwhile, meant that whenever they got called for a search-and-rescue operation, it was safe to assume the missing people were already dead.

“A lot of times,” Taylor said, “all we’ll find is a pool of blood. Body parts in the water.” We were drinking whiskey in his living room, but the numbing effects didn’t soften his words. “They would’ve been dashed against the coral a hundred times already.”

Taylor had real, palpable anxiety about returning to the civilian world, which he was on the cusp of entering. His other deployments had been to some of the worst areas of conflict in the world: the Philippines, the South Korean DMZ and a number of typhoon/earthquake disaster-relief missions that still kept him up at night. He had already attended the military’s joke of a transition course—TAPS—but he came out more confused than when he’d gone in. So after I asked him what he wanted to do when he got out, it didn’t come as a complete shock when he said, “I want to buy a boat and sail it around the world.”

That had been Taylor’s dream since he was a kid. And the military, he said, had been his means to that end. Taylor had been putting away hefty chunks of his salary for years. Enlisted soldiers have a reputation of blowing their hard-earned cash on lavish expenditures or wild nights on the town, but Taylor had made it a point not to fall into that trap. Still, sailing around the world is a common enough dream, and lots of people talk about it. Even I had dreamed of sailing the Greek Isles. What did surprise me was what he said next: “Join me.”

I laughed. I couldn’t help myself. The impracticality of this dream notwithstanding, I had virtually no sailing experience; I was—by all First World standards—flat broke; and I was in the middle of a doctorate program, on course to become an associate professor and a writer. Why he thought I might say yes, I can’t imagine. He didn’t even have a boat. Even so, my natural, initial response, was simply: “Sure. Why not?”

Whiskey had helped fuel that conversation, and a large part of me assumed the whole idea would be forgotten by the time I returned to Scotland. But it wasn’t. In fact, our conversations continued well into the final year of my Ph.D.

I’d been conducting interviews with combat veterans from the Iraq and Afghanistan wars for about five years. My dissertation was a collection of short stories about combat veterans adjusting back into civilian life. And so, after reconnecting with Taylor, I made him one of my authenticity buffers. We worked well together because he’d never hold back. “There aren’t sergeants in the Navy,” he’d say. Or: “It’s a galley, not a mess hall. Nobody says they’re going to eat ‘mess.’”

When Taylor got out of the military four months later, our roles reversed. Where I had looked to him for confirmation, he now turned to me. Taylor would call from his car, after a party, or from home sitting on his bed. His heart rate would be through the roof, as if he were in the middle of a rescue or about to leap out of a hovering helicopter. But he’d been doing nothing of the sort. Talking to a friend. Driving his truck. Staring at a wall.

“Have you heard this before?” he asked. “In the guys you interviewed? Is this normal?”

My answer was always: “Yes.” I’d heard similar variations from every single veteran I’d interviewed. But what struck me most were the similarities between Taylor’s experience and those of combat veterans.

Taylor and his fellow rescue swimmers had adapted to working back-to-back flights; they were frequently denied more than four hours of consecutive sleep; and their job was jumping out of helicopters. They ran off endorphins, epinephrine, cortisol and supplements that simulated the same effects. Taylor’s adrenal and pituitary glands had adjusted to producing excess amounts of fight-or-flight hormones. So when he left the military, those glands didn’t just stop producing; they kept right at it. And when he couldn’t provide an outlet for his pent-up hormones, they’d release of their own accord.

For Taylor, this was all incredibly foreign. And scary. Having no control over your body—when your profession relied on absolute control—is nothing less than terrifying. It feels like you’re losing yourself.

Then the unthinkable happened. Taylor—the fun-loving, generous, excitable kid who had gone from the slowest swimmer in town to captain of the varsity swim team; the rescue swimmer who had dedicated six years of his life to helping others; and one of the most positive, energetic humans I’ve ever known—put a gun to his head and pulled the trigger.

The round didn’t go off.

It’s not my place to describe what drove Taylor to that moment, or how he was able to pick himself up and carry on, but I can say that it was nothing short of a miracle that he survived. And because of it, both of our lives changed forever.

Taylor often credits me with helping him through some of his darkest moments, but it was his dream of sailing, and his determination to see it through, that pulled him out of the dark. He was alone and confused, disillusioned with, and undervalued by, the civilian population. But our proposed voyage gave him a purpose.

Taylor threw himself into this new endeavor, and he began by searching for a boat. Not just any boat though. We needed one that was affordable, and that could withstand just about anything. It took months of research, reading and traveling—not to mention thousands of dollars hauling out boats for surveys—but Taylor applied himself to the task with everything he had.

Meanwhile, I was in a frenzy to finish my degree. It was around this time that I stumbled upon the largest, most comprehensive study of veteran suicides ever released. It involved over 1 million US military personnel who served between 2001 and 2007—the peak of the Iraq and Afghanistan wars—and the findings were startling. Veterans who had not deployed to a combat zone were more likely to commit suicide than veterans who had. Taylor had never technically deployed to a combat zone. And while he was being discharged, despite exposure to a number of seriously traumatic experiences, PTSD

—post-traumatic stress disorder—wasn’t even mentioned.

This sailing trip, then, became something else entirely: a mission and an expedition. It would be Taylor’s own Odyssey—his transition to civilian life—and we would document the entire endeavor. Our plan was to showcase the struggles veterans face when leaving the military, and tell the story of Taylor’s personal journey to overcome them. But to be heard, truly heard, we couldn’t simply sail a road-mapped route around the world; we needed to do something big. Something that would grab hold of the public and maintain their attention long enough for them to see. And to do that, we needed to sail the harshest waters on the planet.

We needed to round Cape Horn.

Taylor closed on a boat in Tampa, Florida, at the end of March—the last possible moment if our plans were going to stay on track—and our fantasy expedition became real. We still had months of work to do, and Cape Horn was just a speck on our charts, but we had a boat. Our journey had begun.

Taylor had purchased a Watkins 36, a Bill Tripp-designed, center-cockpit sloop with a long fin keel and skeg-mounted rudder. As a novice sailor, 36 feet sounded pretty small to me—until I stepped on board. Down below, there was standing headroom. And she was beamy, with room for a good galley and head, a comfortable saloon, and two cabins with berths for three or four crew. A reinforced cockpit Bimini would shield us from stormy weather, and she had wide working decks for sailhandling and maneuvers.

“Plus she’s sturdy,” Taylor said. “She’s built for the high seas.”

It was spring 2017, and I had flown from Scotland to see her for myself. I was not disappointed. But the clock was ticking. If we were to round Cape Horn in a single season, we would have to leave by September at the latest. There were still countless repairs and preparations to make if we were going to sail to the bottom of the world, and neither of us could afford a year of idling. And so our race started.

The next several months were a blur. I was juggling a half-dozen commitments to finish my studies, but in May I still flew back to Pensacola, where Taylor had moved the boat for the refit, then again for all of August, to help work on it. For a month straight, we woke up every morning around 0600, and it wasn’t uncommon for us to return home after sundown. Fiberglass clung to our pores and burned in the showers. The peak summer heat, meanwhile, was suffocating.

But we covered a lot of ground. Together we repaired and painted the hull, replaced and mounted a restored Perkins 4108 engine, and refurbished the entire interior. On scorching-hot afternoons, we’d sew cushion covers in Taylor’s living room. We became whatever our girl demanded of us: mechanics, carpenters, electricians, even seamstresses. And if we didn’t know how to do something, we’d learn. That month was one of the most physically taxing of my life. I sweated and ached more than I ever thought possible. It was edifying.

As the weeks passed, we drew closer to splashing her back in the water, and I began to love our beat-up old boat. All of the work we put into her created a bond unlike anything I’d ever experienced. We even referred to her as our ol’ lady. “Gotta check in with the ol’ lady before bed,” Taylor would say. And so, when it came to naming her, the answer came too easily.

Ole Lady.

We performed all of the rites and rituals required for changing the boat’s name before I returned to Scotland. Then a month later, and five days after submitting a hardbound copy of my final dissertation, we cast off our lines for the open ocean.

The first leg was a 600-nautical-mile stretch across the Gulf of Mexico. It was September 25, 2017. Smack-dab in the middle of hurricane season.

Attempting to detail here every adventure and misadventure of what next transpired would be an incredible disservice to Taylor, Kellen Warner, Jonathan Rose, and all of the many other veterans who joined us, physically or vicariously, at some point along the way. But I will say that we were baptized by fire.

Crossing the Gulf turned out to be one of the greatest trials of our entire trip. We certainly knew what season it was. Hurricane Harvey had just flooded the Houston area, and Miami had narrowly dodged its dance with Irma. With the addition of Maria—which obliterated the Dominican Republic—the 2017 hurricane season became the costliest of all time. But we were not to be dissuaded.

For one, we were already facing a tightened timeline to get to Cape Horn before winter. Not that we felt prepared for the Horn. We weren’t even prepared for the stormy Gulf of Mexico! But there’s an axiom that spoke true to us then, which I stand by today: “If you wait until you’re fully prepared, your boat will never leave the harbor.” So Taylor called one of his Navy buddies, Kell Warner—who took a week’s leave to help us reach Cancun—and we planned our departure around a high-pressure system moving south. Our plan was to ride it to Mexico.

But…the forecast high pressure never came. We enjoyed about two days of smooth(ish) sailing before the storms began, and when that first major front hit, well, it could’ve been disastrous.

Taylor had shortened our sail plan well in advance of the front, with our smallest jib and a triple-reefed mainsail. But when this storm struck, it did so all at once. From my spot on the helm, it felt like running into a wall. The wind and seas, one moment coming from port, almost immediately shifted hard to starboard. The boat heeled heavily, the mast just a few feet off the water. Waves were breaking over the bow and across the deck. We needed to fall off to a broad reach, but to do so we had to drop the main.

I was hardly aware of the evolution of the maneuver. It was all I could do to keep our mast out of the water.

Together, Taylor and Kell moved up the deck. They hadn’t even reached the mast when a wave broke over the bow, the kind of wave I’d seen only in movies, a proverbial wall of water rising out of a black sea. It was like diving headfirst into the River Styx. It broke on Taylor and Kell, crashed into the Bimini, and blurred my view completely. I thought the whole boat had been swamped, or that we had capsized.

Once everything cleared, Taylor and Kell were gone. No headlamps flashing on deck. No silhouettes moving in the dark. Only the shrieking howl of the wind. The thought that we could die on this journey had occurred to all of us a number of times. But never, in all those imaginary scenarios, had I imagined it would come so soon.

They had to be in the water, astern, adrift. I had to turn around. I wasn’t sure I could. But I had to try.

I braced myself to spin the wheel and whip the bow around after the crest of the next wave when a speck of light glinted off the jib. It was so dark, with rain so thick, that I knew it couldn’t be anything else. My grip slackened. Together, as if a single body in motion, Taylor and Kell rose from the forward edge of the bow. They’d been swept off their feet, knocked down and thrashed about, but both had managed to grab rigging and stanchions before being washed overboard. They were alive.

We dropped off Kell in Cancun after an eight-day Gulf crossing, and celebrated surviving what we hoped would be the most difficult leg of the voyage. Of course, we were wrong. Storms to come would be much worse. But we had survived our initiation; it was a trial that we sorely needed and would rely upon going forward.

It would take nine more months to cross the equator into the Southern Hemisphere, months riddled with obstacles. We battened down for Hurricane Nate off the Yucatan Peninsula, and later withstood two tropical storms off the Honduran island of Roatan. Our engine seized after a pair of oil lines burst in the middle of a tropical depression that struck between Honduras and Nicaragua. We were stranded in the middle of the Caribbean Sea—without an engine, with no breeze, for two weeks. When we finally limped into Colón, Panama, we were parched, malnourished and eating peanut butter out of a jar.

We transited the Panama Canal in early December 2018, and by the time we reached Ecuador, we had punched each other in the face, spent our life’s savings, and faced down pirates off the Pacific coast of Colombia. We’d also nearly given up on the voyage a handful of times, the most recent being right before John Rose, a former rescue swimmer, volunteered to help us sail from Ecuador to Chile.

The three of us drifted into Valparaiso after over a month at sea, arriving in late April 2018, sunken-eyed and hungry, in the most confusing landfall of our journey. We had just sailed 3,200 nautical miles without an engine. Our transmission had failed, for the second time, a few hundred miles off the coast of Ecuador, again leaving us becalmed. A fire in the engine compartment almost cost us our lives. We had been rationing food, were taking on water from a crack in the bow, and had snapped a furling line in the middle of a storm. We had totally missed our original, proposed plan to round Cape Horn. Our Ole Lady was falling to pieces.

“It’s time to call it,” Taylor had said the morning after our engine fire. We were becalmed and surrounded by a glassy, windless ocean. “This boat’s not going to make it. We’ll scrap her in Valparaiso. Use the money to fly home.”

We found a pub in Valpo, took turns cleaning up in the men’s room, and inspected the alien features of our reflections. Then we huddled into the dry warmth of a corner booth and allowed the simple pleasures of hot food and a cold beer to wash over us. It took time for our cellphones to charge, and even longer for the messages to pour in. There was going to be a treaty with North Korea, John said. Taylor announced that his sister was having a baby. Amy Flannery, a producer of documentaries, wanted to help us tell our story. Glasses were raised. Pints were drained.

Then Taylor read a message that overshadowed the rest.

“Serna’s dead,” he said. The words fell onto the table. He was already blinking tears out of his eyes. “He committed suicide.”

“No,” John said. He turned to his own phone for confirmation. “Not him.”

Serna was a fellow rescue swimmer. He had deployed with Taylor and John, but he was more than a friend. He was their brother. He was the guy everyone wanted to be around. Serna had enlisted because he believed in serving his country, and he became a rescue swimmer because he wanted to help people. He was the embodiment of rescue swimmers everywhere, but—more than anything else—he was a good man.

There had been a handful of other times on this journey when we’d bent to the point of breaking. Serna’s death hurt. Bad.

We didn’t change our minds overnight. There was no conversation about continuing on despite the risks. The choice was made gradually. We were broken; hell, we were broke; there was really no reason to believe that we would succeed. But we couldn’t give up. We were still in a position to make a difference, to help our friends and our peers. To do nothing would’ve been worse than to try and then fail.

Before flying back to Texas in June 2018, Taylor found a marina in Valdivia where we could store Ole Lady for the Southern Hemisphere winter. John spent the summer teaching sailing courses off Lake Michigan. I began working with FreshFly Films in Philadelphia to transform our voyage into a feature-length documentary. It took a Kickstarter campaign, with contributions from our small—but incredibly loyal—following, to get us back to Chile. But we made it happen. And when we returned to Ole Lady that November, we were reinvigorated and ready to finish what we had put into motion two long years before.

Our work was far from done. Ole Lady was still hurting. There were still repairs to be made and provisions to find. We had no idea what would be available to us in Puerto Williams, or our next landfall after rounding Cape Horn. We were preparing for the unknown. And we had to be ready for, and anticipate, everything.

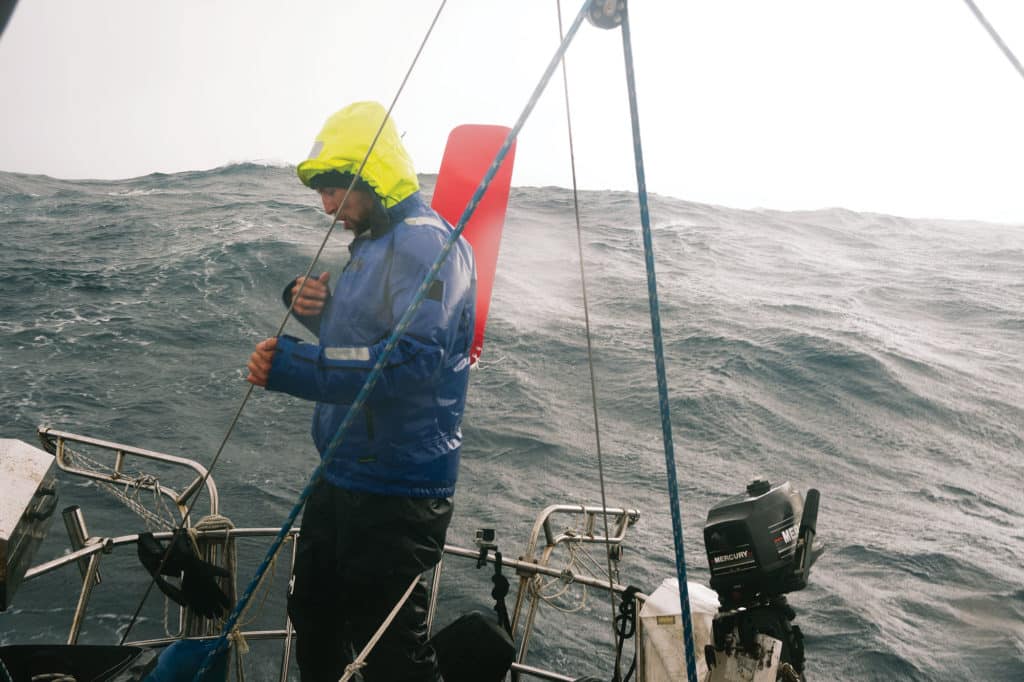

For the most part, I’m proud to say, we did just that. Despite facing the worst seas of the entire trip—and battling more snapped lines, shattered blocks and broken rigging than ever—our next leg, from Valdivia and into Patagonia, was, by far, the one we were most prepared for. We even addressed a sheered roller furler at the mouth of the Magellan Strait, in some of the steepest waves I’ve ever seen.

When we finally checked in to Puerto Williams on Christmas Eve 2018, we weren’t just tired; we were wiped out. What we wanted now, more than anything, was to be done. To be safe. To be finished with what had evolved into our own real-life Odyssey. And that played into our decision to just keep going. On December 26, just two days after making landfall at Puerto Williams, we cast off and steered west down the Beagle Channel.

We approached Drake’s Passage from Paso Picton, traversing Bahia Nassau before looping around the Horn from west to east, to ride the prevailing westerlies past the cape, then tuck back inland behind the shelter of Isla Deceit. The wind began picking up and heading us later that morning though, and by late afternoon, we had to tack our way south. Night fell by the time we reached Bahia Nassau. I took the midnight watch.

Bahia Nassau is the notorious stretch of water that Charles Darwin coined “the Milky Way of the sea.” Joshua Slocum recalled it as the scene of “the greatest sea adventure of my life.” It lived up to its reputation.

Even in these relatively calm conditions, the wind kept shifting from all directions. Swells from Drake’s Passage rebounded off the surrounding islands, and struck back with surprising size and speed. Hours seemed to pass where it was difficult to discern if we were going forward or backward. It was a cloudy night, and so dark that, at times, I could hardly see my hand in front of my face. An eternity stretched before the glow of dawn, and at 0400, I handed the helm to John. We hadn’t even rounded the Wollaston Islands.

John spent the rest of the morning negotiating the currents and headwinds at the entrance of the Hermite Strait, the final stretch before Cape Horn. But he managed to set up Taylor for a run at the Drake Passage. Taylor hit his stride. The sun broke through at the beginning of his watch as we flew south at 5 knots, against the current.

We passed False Cape Horn, off Isla Hoste, and broke into the Drake. By now it was afternoon, and the conditions were…disheartening. We were disoriented, and not a little dismayed, to meet sharp, biting winds from the east. This wasn’t the weather window that had been promised—the calm winds and blue skies that were forecast to follow the preceding storm—nor was it the supposedly reliable westerly breeze that we had planned our entire voyage around. Instead there were low dark clouds on the horizon, a gray haze of rain to the east, and large, steep swells pushed up by a continental shelf that climbs from over 4,000 meters to a mere 100 meters within a few kilometers. We were battling upwind, into waves the size of large buildings, and against the current.

Yes, it sounds absurd, but we’d been hoping for a calm sail around Cape Horn. We’d even had conversations about cruising within a mile of the cliffs, posing for pictures in the sun, even landing on shore (drawing straws for who had to remain on board) and hiking to the monument, and getting our passports stamped by the lighthouse operator. It had been done before, and it had been our dream since the very beginning to bask in that moment. We imagined it would be an act of balance, of karma, after all the hardship we had faced to get there.

It wasn’t going to happen.

As quickly as Cape Horn appeared over the horizon, she faded behind a veil of mist and rain. A gale was approaching, and we were still 20 miles away.

Despite the warnings and lessons of our journey so far, we chose to keep going. We were determined to keep on as close a course as possible to the Horn itself. We reefed down to maintain our closehauled track, but the conditions weren’t having it. We were slamming so hard, we felt it in our bones.

After flying over a steep wave that literally knocked us off our feet, Taylor eased the mainsheet and furled most of the jib. Cracked off slightly, on a true wind angle of about 60 degrees, we were now on a heading to pass the Horn some 20 miles offshore, in the dead of night. But if things deteriorated further, we’d have no choice but to turn tail, bear away, and abandon the Horn attempt.

I was devastated. John was furious. But Taylor was heartbroken. We were so close. John disappeared below, and when he returned with a bottle of whiskey, Taylor let it out.

“Everything we’ve worked toward,” he said. “All of the shit we’ve put up with, and all we wanted was a break. Why was that so much to ask?” He looked up as he spoke, his eyes welling.

Then something remarkable happened. The sun, behind layers of mist and cloud, glowed through the haze. The waves and wind weren’t letting up, but the skies were hinting at a respite. When the wind started backing from the east to the north, we allowed ourselves to hope once more.

It didn’t happen in a single moment, but gradually, almost imperceptibly, our course was lifted inland, and we came within 3 miles of the legendary rock before passing it. The sun broke through, igniting that battered rock, and the curtain of rain that had veiled Cape Horn all day lifted to reveal her face—in all of its mean and malevolent glory.

Cape Horn demands a tribute from those who pass. Charles Darwin realized this during his first passage on Beagle, and we learned it on Ole Lady, after paying a toll on both sides. The fair weather held through late afternoon. We posed for pictures, launched the drone, and shared a celebratory dram of whiskey in the cockpit. But as the sun fell over the Isle of Deceit, we were blasted by another gale, this one with twice the force of the last.

Ultimately we did turn back—passing Cape Horn a second time—before cutting back up the passage we had come from in the first place. We motored our way up tight inlets into the Beagle Channel and aimed for Puerto Williams the following evening, but only after our engine overheated and we had to tack upwind to the Chilean port. We arrived at 0300 on New Year’s Eve, and the rest is, well, history. Our production team flew down to Ushuaia, Argentina, a month later to interview us in Patagonia. Taylor sold the boat to a young Chilean captain. Then we flew home to begin postproduction for our documentary, Hell or High Seas.

There were no parties to celebrate our return; no news outlets stood by to film our reunion with loved ones in the airport. Flying home was as anticlimactic an ending as we could’ve imagined. And yet, it wasn’t the end. Because the real journey is just beginning. Our expedition to sail Cape Horn was the first step, and Hell or High Seas is going to be the next. But more will need to follow if we’re going to make a difference. Our soldiers, for instance, need a more comprehensive out-processing program, facilitated by veterans and civilians—not the military. We need longer transition periods for veterans to reassimilate, with optional pipelines that educate as well as exercise the mind. But we also need a change of culture, not only in the military, but also outside it. I emphasize the latter because we, as civilians, are our military’s first point of contact when they return home. We set the tone for the rest of their lives.

Sailing was Taylor’s transition period. It offered an ideal mixture of serene reflection and adrenaline-packed fights for survival. We dealt with hurricanes and gales, but there were also moments of profound beauty and tranquility, from the sublime, raw grandeur of Patagonia to the ripple of bioluminescent plankton in the wake of dolphins diving at night. And so, as our trip progressed, sailing became more than an adrenaline outlet or a balance between the highs and the lows. It became a reminder about the value of living.

But there’s still a question: Is Taylor going to be OK?

I have much to say on that end—and I’ve got a lot of faith in him—but right now, after two years together on the high seas, the reality is that I don’t know.

What I can say is that he’s survived the most dangerous period of a rescue swimmer’s life—his first year out of the military—and that, by all points of evaluation, means he’s doing better. Most of this progress came from learning to live with PTSD rather than trying to overcome it. But the cost of his service will continually affect his body and mind. Taylor will always have his demons, and no measure of therapy or sailing is going to change that.

But there were other takeaways that neither of us anticipated. Like how, after all that we’d been through, it wasn’t rounding Cape Horn or achieving our goal that guided Taylor in his transition home. It was the sense of purpose that it gave him, and it was the journey, the adventure and the excitement of rediscovering the world, of recalling that there will always be more for us to experience.

And to explore.

Stephen J. O’Shea is a writer and documentarian—and now sailor—who tells stories for a living. His first book, From the Land of Genesis, was published in 2020, and he is a credited writer, videographer and producer for the upcoming feature documentary Hell or High Seas, about this epic journey to Cape Horn. Taylor Grieger, meanwhile, is captaining sailing charters out of Kemah, Texas, and delivering sailboats around the globe. He is currently the director of operations for veteran sailing nonprofit organization American Odysseus Sailing Foundation (amodsailing.org). His next dream, to lead proper high-latitude expeditions with veterans, is still very much alive.