Nine days out from the Azores, I steeled myself as we approached the Royal Cork Yacht Club in Crosshaven, Ireland. Quetzal, my Kaufman 47, and her skipper have a fondness for the Irish, and my arrivals—and departures—have been known to get a bit out of hand. Once the lines were secured and customs and immigration officials satisfied, the dangerous part of the passage commenced: the celebration. My Irish friend Pat was on hand to welcome us, and before we knew it, a party broke out in his garden on a bluff overlooking the harbor.

I blame Phil, Pat’s lovely wife, because she kept the wine flowing as our discussions ricocheted from Brexit to presidential politics to church scandals. Eventually we left the political and religious minefields astern and broke into song. In Ireland, once the singing starts, it’s all downhill—a point that my crew was only too happy to remind me about in the coming weeks; later that evening, their besotted skipper and erstwhile navigator insisted that we had to walk uphill to get back to the boat.

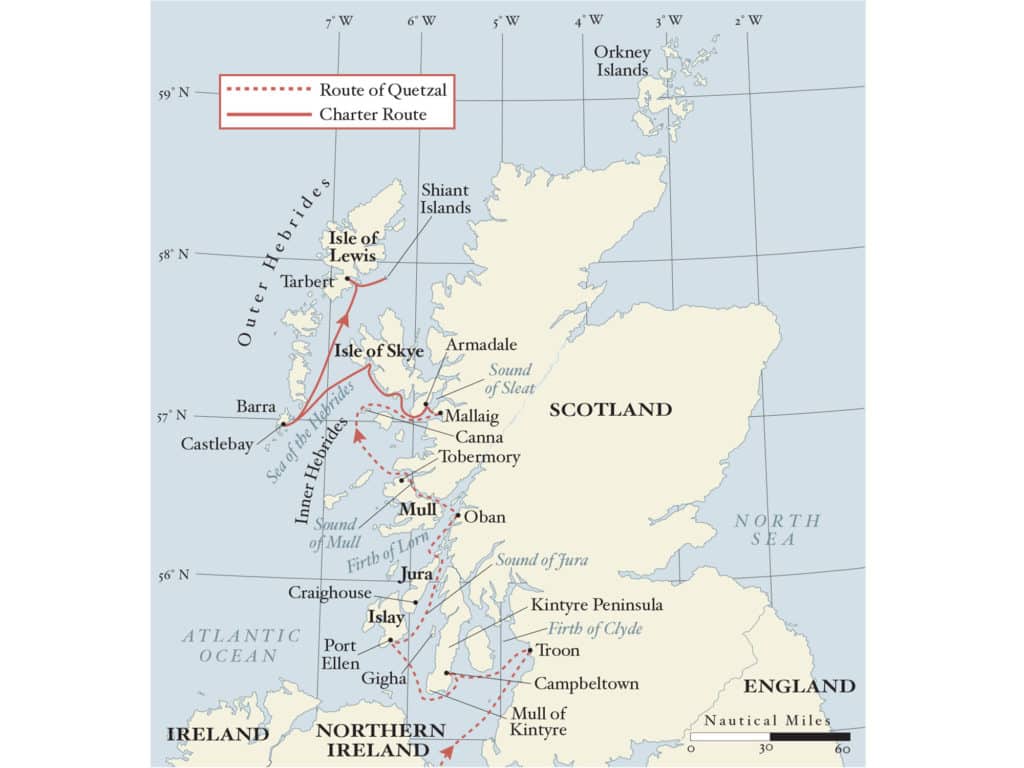

Sober, humbled and reoriented, the next morning I spread my collection of Imray charts across the saloon table. While it was good to be back in Ireland, Crosshaven was just the staging point; we were bound farther north, to the west coast of Scotland. Paper charts fuel dreams in a way that electronic charts, beholden to their devices and GPS overloads, never will. One by one I unfolded C-57 through C-65, plotting a course that would take us from Cork to Dublin, then on to the Firth of Clyde and beyond. Once in Scotland, we would have a couple of months to explore the Inner and Outer Hebrides, one of my favorite cruising grounds. I arranged our “sailabouts” into four legs.

The Usual Suspects

the crew for leg one—400 miles from cork to oban, Scotland—included the usual Quetzal suspects: Alan from Lunenburg, Ron from Chicago and Bruce from Maryland. This two-week cruise was the reward for their knee- and back-breaking efforts the year before when they helped remove Quetzal’s teak decks (see “Confessions of a Teak-Totaler,” Hands-On Sailor issue, 2018). By sheer coincidence, our route would take us to several ports with distilleries, and it seemed if a wee dram of single-malt whisky now and again helped ease their pain, it was the least I could do. In Troon, on Firth of Clyde, I arranged to pick up my daughter, Narianna, and her boyfriend, Steven. Nari, who grew up on Quetzal, understands her old man’s cronyism; she knew what to expect (Steven was in for a few surprises). Pat, a Quetzal veteran and Gaelic speaker, also shipped aboard, and he would ultimately, bravely attempt to translate the all-but-indecipherable Scottish brogue for the rest of us.

The weather was almost unnervingly pleasant as we made our way up the Irish Sea. We closed the coast near Dalkey Island, and Pat pointed out the exclusive Killiney neighborhood where Irish celebrities, including Bono, live. We made our way to Dun Laoghaire on the bottom of Dublin Bay and took the train into the city. Then we were off for Scotland, skirting the Isle of Mann and leaving Belfast Lough to port. We had another near-perfect sail, reaching before moderate southwest breezes. Dodging fast ferries was the only challenge. I had a notion that Neptune would pay us back for this easy run to Scotland (our return to Crosshaven later that summer proved my premonition right).

RELATED: Faroe Islands Sailing Adventure

In Troon, we picked up Nari and Steven, and hastily prepared to get underway. So much for fair weather: Fish-scale clouds sprawling across the sky wrapped a halo around the sun. The forecast called for gale-force winds late that evening. A local sailor strolled by and assured us that the forecast was off by 24 hours. He was nattily outfitted in leather dress shoes, designer jeans and a fancy, black, embossed Hugo Boss T-shirt. “The met office got this one wrong,” he said knowingly. “Don’t worry, it’ll be OK tonight. But tomorrow night, watch out.” We politely thanked him for his advice before dismissing him as a crackpot. We were counting on our freshly downloaded GRIB files for weather input, not fashionable local knowledge. We angled back across a lumpy Clyde, bucking headwinds and foul currents before making our way to Campeltown near the southeast corner of the Kintyre Peninsula. The marina is at the head of a protected inner bay and tucked into the city center with several pubs nearby, a perfect spot to ride out a gale.

The gale never materialized, and the next morning we were underway again, making our way toward the Mull of Kintyre, where we had an appointment with the flood tide. The Mull, which in Gaelic means “headland” (more or less), is more famous than it should be. And not because it’s the cradle of Scotland, where fifth-century Irish monks first came ashore; or for its windswept landscapes, or fearsome tidal overflows; or even because it’s considered the true starting point of Hebridean cruising.

No, it’s famous because of an annoying-but-irresistible Paul McCartney song that lodges in your brain like a computer virus. Ron set up the speaker, and Alan and I led the chorus, bellowing, “the Mull of Kintyre, the Mull of Kintyre,” as we rounded the headland and rode a 3-knot tidal stream into the Sound of Jura. Steven looked concerned, realizing that he was stranded with us for a week.

We were bound for Islay which, according to the Clyde Cruising Club Sailing Directions, “is famous for its whisky, not surprisingly, as there are seven distilleries on the island.” We secured Quetzal along the small pontoon off Port Ellen and made inquiries about visiting a few the next day. Two English ladies cruising in a vintage Camper Nicholson 32 sloop took the slip next to Quetzal. They were nervous and short of mooring lines. We loaned them a few stout ones, helped them tie up, and wondered what all the fuss was about. We found out just after dark as a torrent of cold rain preceded the arrival of a vicious front. Shrieking winds gusting to 45 knots raked the harbor. As Ron and I braved the icy blasts to check our lines and fenders, we both had the same thought: Hugo Boss was spot-on!

In the morning, Alan made a hearty breakfast, which included our new favorite dish, smoked haddock, fortifying us for the task ahead: whisky tasting. We followed a well-marked path to the Lagavulin distillery nestled along a rocky cove. Being education-minded sailors, we completed our first distillery tour and learned a few of the secrets of making fine whisky, but there was so much more to learn. Islay is famous for its peaty single malts, and we took a liking to a smoky 16-year-old. On the way back to the boat, Nari and Steven climbed through the ruins of the 13th-century Dunyvaig Castle, and then joined us for a tour of the Laphroaig distillery, just for comparison’s sake.

Working our way north, we tarried at the small, welcoming island of Gigha before carrying on to the forbidding and sparsely populated Jura. The Jura distillery dominates the island’s only town, Craighouse, where we picked up a mooring in a gathering breeze. We braved blustery winds to get ashore, not wanting to leave Jura off our list of distillery tours. Whisky aside, Jura is best-known as the place where author George Orwell nearly drowned before he finished his masterpiece 1984. After World War II, Orwell retreated to Barnhill, a solitary cottage on a brooding hillside on the north end of the island. It was, in his own words, “in an extremely un-get-atable place.” Orwell, an avid mariner, had a small skiff with an outboard motor, and he often plied the sound. During one outing, he mistimed the tidal current, and he and his young son were caught in the infamous Corryvreckan whirlpool. Their boat capsized, and they were lucky to struggle to a rocky shoal. They spent hours clinging to the rocks before being rescued by passing fishermen. 1984 was half-written at the time.

Quetzal’s crew did a better job of timing the tides as we sailed northeast into the Firth of Lorn. The favorable current added 4 knots to our speed over ground. Bruce manned the helm as we picked our way around rocks and skirted shallows despite patchy fog. We sped into Oban’s expansive harbor and eased into a slip at Oban Marina on Kerrera Island, across from the city. Steven, who was really turning into a sailor, noted that we were in luck; there was still time to catch the ferry into town and make the last tour at the Oban distillery.

The Tropical Wimp

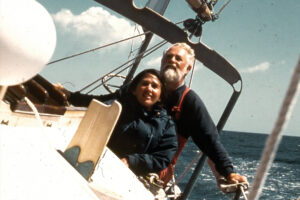

the leg-one crew departed, and the second leg of our Scotland summer began when my wife, Tadji, arrived at Oban Station. The prospect of an unfettered month of cruising gave us the luxury of lingering in one of the finest harbors on the west coast. Oban circles an expansive bay and has everything a cruising sailor needs: shops of every description, and a selection of pubs, lovely walks and a distillery. We eventually sailed into the Sound of Mull, or the “milk run,” a protected passage between the rugged highlands to the west and the enchanting island of Mull to the east. It’s the sea road to the “Small Islands” of Muck, Eigg, Rum and Canna. A lighthouse, designed by Robert Louis Stevenson’s father, Thomas, marks the bottom of the sound, and the charming fishing village of Tobermory is near the top.

With a gentle breeze from the south, we popped the spinnaker for the short sail up to Tobermory. Out of nowhere the winds piped up to 20 knots, then 25, and we struggled to douse the kite. Five minutes later, we had two reefs in the main and a deeply furled headsail. Two miles from Tobermory the winds abruptly dropped, and we entered the harbor under full sail, rounding out a typical sailing day in Scotland. The sailing directions warn that Tobermory is the “port of lost cruises.” It’s certainly a postcard setting, and Tadji and I fell under its spell. We tarried for a week, content to explore the colorful fishing village and hike lush trails nearby. That Tadji was enjoying Scotland was a pleasant surprise and the result of a major upgrade to Quetzal.

A self-declared “tropical wimp,” she hibernates when the temps drop below 70 degrees F. I am drawn to cold places and find high latitudes alluring. The solution to this dilemma was the addition of a hard dodger and full cockpit enclosure. Designed by my brother-in-law, Trevor, and fabricated at his boatyard in Solomons, Maryland, the “T Top” (or Tadji Top) is a true work of inspiration. The frames for the hard dodger and Bimini are welded aluminum. The dodger panels are high-density foam lightly glassed over, and the windows are polycarbonate. It’s robust, permits reasonable visibility, and keeps the cockpit warm and dry. The adjacent Bimini is a mix of waterproof fabrics, and the roll-up panels can be quickly deployed. It’s been a game-changer for Tadji. Sitting in our “patio” at the marina in Tobermory, we tried not to appear too smug as we watched crews of other boats, clad in full foul-weather gear, endure the rain and cold in their exposed cockpits.

We had a rollicking sail to Canna, the most westerly of the Small Islands. The natural harbor promised excellent protection from the 30-knot southwest winds predicted for the evening. The wind backed to the south as we made our approach, and we were tempted to pick up the mooring under sail but chickened out at the last moment. With two mooring lines forming a bridle, low-slung Quetzal hardly moved in the Force 8 gusts. A ruined church on the bow, looming in and out of the mist, made for an eerie but starkly beautiful setting. Ensconced in our full enclosure, we had front-row seats to watch a Scottish gale unfurl.

A few days later, we sailed to the bustling mainland harbor of Mallaig, where we would leave Quetzal for a week. For Leg Three of our Scotland cruise, we arranged a charter trip around the Isle of Skye and a visit to the Outer Hebrides with dear friends and frequent shipmates Ken and Denise, Sean and Youyi, and Chad and Ryan. The four-cabin Jeanneau Sun Odyssey we chartered from Isle of Skye Yachts offered room for eight, and also had a diesel heater, which clinched the deal for Tadji. We took the ferry to Armadale, just a few miles across the Sound of Sleat, and picked up our boat, appropriately called Explorer of Sleat.

Slurping Cullen Skink

skye is one of the best-known islands in the hebrides, and for good reason: It’s a mix of mountainous terrain, protected natural harbors and attractive villages. A new bridge linking it to the Scottish mainland has helped fuel something of a tourist boom. We motored most of the way to Loch Scavaig on the southwest coast, but that didn’t spoil the dramatic approach. Set amid 3,000-foot mountains, the harbor is a natural bay framed by cascading waterfalls and protected by rock sentinels. We passed dozens of seals sunning themselves on mossy rocks as we crept into an enchanting inner pool and anchored in 10 feet of water. After exploring ashore, we exploited the lingering summer light at latitude 57 degrees north and rode a freshening breeze to sail to Loch Harport.

We snagged a spot along the pontoon at Carbost, a tiny village and home, coincidentally, of the Talisker distillery. We dined at the quaint Old Inn, and Tadji introduced the crew to Cullen Skink, which sounds more like the name of a bumbling detective in an old BBC sitcom than a delicious fish soup. Tadji and Ken also began their love affair with sticky toffee pudding, and made it their mission to find the best pudding in the Hebrides.

We woke to a brisk northwest wind, and after the obligatory tour of the Talisker distillery, seized the opportunity sail to the Outer Hebrides on a sweet reach. We made our way to Barra, near the southernmost point of what the locals call “the long island,” a phrase linking the 100-mile stretch of islands, islets and rocks that make up the Outer Hebrides. This rugged archipelago, sweeping to the northeast, juts a craggy chin into the North Atlantic, providing a lee for the waters to the east: the Sea of Hebrides, Little Minch and North Minch. The islands of Inner Hebrides benefit as well, and are surprisingly lush when compared with their windswept western cousins.

A new pontoon is a welcome addition in Castle Bay, named for the 14th-century Kisimul Castle perched incongruously on a shoal and surrounded by water on all sides. The facilities throughout Scotland are excellent, and it never fails that someone always stands by to catch a line no matter the weather. From Barra we nosed into the tiny natural harbor of Acairseid on the island of Eriskay and picked up one of two moorings. Eriskay is famous for its prince and its whisky. The fine sand beach on the windward side is where Bonnie Prince Charlie landed in his ill-fated attempt to reclaim the throne of England through the Stuart line. The whisky story seems more tragic.

On a dark February night in 1941, cargo ship SS Politician went on the rocks in the treacherous waters between Eriskay and South Uist. The next morning, the locals managed to rescue the crew; miraculously, no lives were lost. Once ashore, some of the crew let on that the ship was loaded with an unusual cargo: 264,000 bottles of malt whisky. The booze was bound for the American market to raise money for the war effort; it was for export and no duty had been paid. This inconvenient fact didn’t stop the locals from conducting midnight raids to “rescue” the whisky. When the customs officials arrived from England, they decided to destroy the ship to prevent any more illegal activity. As the ship was blown to pieces, one bewildered islander said, “Dynamiting whisky—you wouldn’t think there’d be men in the world so crazy as that!”

We had a lively sail to Tarbert on the south end of Lewis and Harris island. I was impressed as the Jeanneau Sun Odyssey 43.9 stood up to the blow, and happily carried on with a double-reefed main and a deeply furled headsail. Tarbert is home to the famous Tweed shop, and I had to convince Tadji that I really didn’t need a kilt. We were away early the next morning for an appointment with several thousand puffins. Sean launched his drone and captured our departure as we headed for a small cluster of islands, the Shiants. I had just finished a delightful book, The Sea Birds Cry, by Adam Nicholson. He describes spending summers camped in the remote Shiants as a boy, mesmerized as the islands are visited by hundreds of thousands of puffins. Alas, we were a week late; all the puffins had finished their business ashore and had headed out to sea. A few gulls and a handful of gannets were the only occupants as we tacked through the craggy islands, futilely searching for just one wayward puffin.

Tadji and I returned to Quetzal and hastily made our way back to Oban. She was off to Paris, to continue her French lessons, and I greeted the crew for Leg Four: the return passage to Crosshaven. Sitting in the Corryvreckan Pub along the Oban waterfront, Scott, Gretchen and Brant studied the gloomy scene on windy.com. They were all Quetzal vets and knew that the passage south would be challenging. Still, 25- to 35-knot headwinds, driving rain and sub-50-degree F temperatures were a bit beyond challenging and bordered on misery. Scrolling ahead a few days, there was little change in the weather. “Hmm,” Brant concluded, “it looks like it’s going to be uphill sailing all the way back.” I smiled and recalled my drunken episode back in Crosshaven. Yes, there’d been (and would be) some challenges, and yes, some of them were self-inflicted. But they’d all been worth it.

John Kretschmer’s latest book, Sailing the Edge of Time, has just been released in paperback and as an audiobook. John and his wife, Tadji, conduct offshore sail-training passage aboard their well-traveled 47-foot cutter, Quetzal. In 2021 they will launch “The Big One,” a circumnavigation that will take them to latitudes big and small and longitudes far and wide. They will incorporate select training passages along the way and also report for Cruising World from far-flung quay sides.