Among the big challenges when planning a long-distance passage can be knowing when to leave, how to take advantage of the best weather windows along the way, and what waypoints to set to get you there the quickest or with the least exposure to unpleasant points of sail or conditions. Thankfully, the cruising navigator has a bevy of tools from which to choose, including weather-routing and passagemaking apps, and software and services that have been developed and refined to take advantage of the computing power found in laptops, smart devices and chart plotters.

While these digital tools typically aren’t free to use—and usually require some form of connectivity and product familiarity to deliver the best results—once downloaded (and mastered), sailors can enjoy better weather, more-comfortable conditions, faster transit times and greater situational awareness of what might lie ahead. Generally speaking, these navigation aids are designed to be intuitive and user-friendly, and depending on which you choose, will work with communication devices ranging from satellite phones to skinny-bandwidth transponders such as Iridium’s Go or Garmin’s inReach and, of course, full-on FleetBroadband or very small aperture terminal satellite systems. Some of the tools are even available to boats equipped with old-school single-sideband radios.

But how one gets their weather data is often less important than the quality and timeliness of that information, which usually comes in the form of gridded binary, or GRIB, files. While third-party weather-routing companies commonly leverage GRIB files with their proprietary algorithms to create weather forecasts and routing advice, the raw data contained in GRIB files usually comes from official government meteorological offices. Two common sources include the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, which releases its Global Forecast System four times a day, and the European Union, which produces European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts—considered the global gold standard—twice daily. As with all pieces of time-sensitive information, cruisers who can access the internet to either download fresh GRIB files or to run their routing on a service provider’s cloud or website will usually experience better, faster and smoother passages than those relying on old data.

These weather-routing and passagemaking tools typically use one of two strategies for computing the best departure times and routing options. Traditional PC-based software, such as TimeZero or Expedition, require outside information (GRIB files or some other weather forecast), which the software then crunches locally on a navigator’s laptop or chart plotter to create the best itinerary. Another option involves app-, cloud- or website-based products that oftentimes give cruisers access to a server, which performs this computing remotely and then sends the results to the crew aboard the boat.

While the net result is often similar, each has its upsides. Onboard passagemaking and routing software means that the information and the means to process it are close at hand should outside communications go down, or if users want to run any offline route planning to weigh alternatives. Cloud and website services, on the other hand, usually have access to a range of weather forecasts and GRIBs, so the crew needs to download only the resulting routing information, which can be as simple as a series of waypoints, rather than the significantly bigger weather files. This means less airtime or consumed data for anyone using satellite communications.

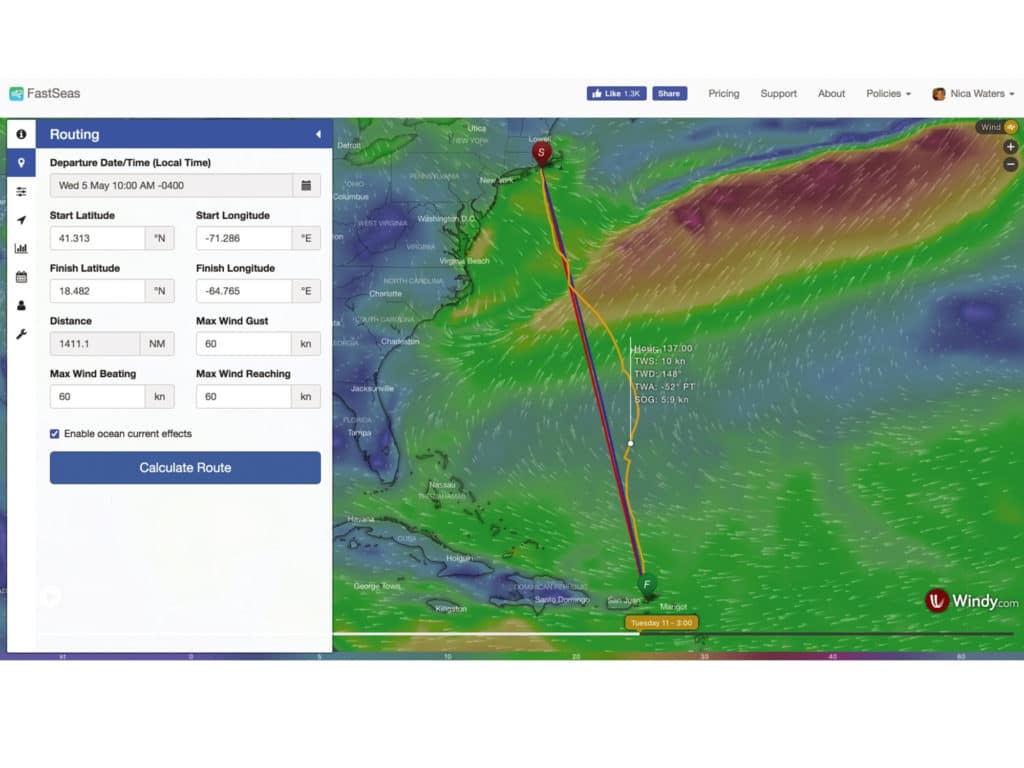

“The software uses weather-forecast-model data to find the optimal route for a given passage by evaluating all available routes for that passage,” says Jeremy Waters, who built and actively uses FastSeas, a website-based passage-planning tool that resides on an Amazon Web Services-supported cloud and relies on GFS GRIB files.

Users create an online account that includes their vessel’s specifics, including its polars, and they tell the website where they want to go, along with other trip parameters and preferences. The website generates and then sends the boat GPX files, which they can download using some form of long-range communications system such as a satphone, Iridium Go or Sailmail in the case of SSB operators.

While FastSeas doesn’t offer an app with a built-in GRIB viewer, anyone with internet access can look at animated weather maps, courtesy of windy.com, on the FastSeas webpage. Alternatively, FastSeas can also send simple routing updates via text message containing waypoints and simple forecasts at different waypoints to a Garmin inReach satellite communicator. “The Iridium Go and Garmin inReach provide economical satellite-communications options to offshore sailors, and FastSeas is designed to provide updated route data while working within the device’s technical limitations,” Waters says.

Other app- and web-based tools deliver even more in-depth weather and weather-routing information. “PredictWind’s weather router uses a complex algorithm to give sailors the fastest—or safest—passage from A to B based on their boat’s expected performance in the forecast weather and ocean conditions for the specified period,” Nick Olson says. He is one of PredictWind’s two principal developers.

PredictWind offers two apps: PredictWind and PredictWind Offshore. The offshore app also gives users access to Global Maritime Distress and Safety System forecasts, observations and satellite imagery, and, if the boat carries a compatible and properly networked GPS tracker, allows the skipper to view detailed forecasts from six different global weather models. These include GFS, ECMWF, SPIRE and UKMO, as well as PredictWind’s proprietary PWE and PWG forecasts, the latter of which are created using ECMWF and GFS data (respectively) and PredictWind’s proprietary algorithms.

A boat owner uploads their vessel’s polar information to PredictWind (either via the app or website) so that the service can create a bespoke routing solution. “Avoiding bad weather is a key element to safety and enjoyment in any passagemaking,” Olson says. “We also have a departure-planning tool that can aid in choosing the best time to leave for a passage.”

In addition to parameters such as vessel polars, destinations and passage dates, some weather-routing services also allow the navigator to stipulate the maximum acceptable windspeed and wave height, as well as maximum time on a particular point of sail that they wish to encounter on their passage.

While weather routing is an invaluable tool for passagemaking, so too is the ability to plan a passage at home and then seamlessly share this routing information—complete with weather updates—with onboard chart plotters. Numerous options exist for this, in the form of apps and software.

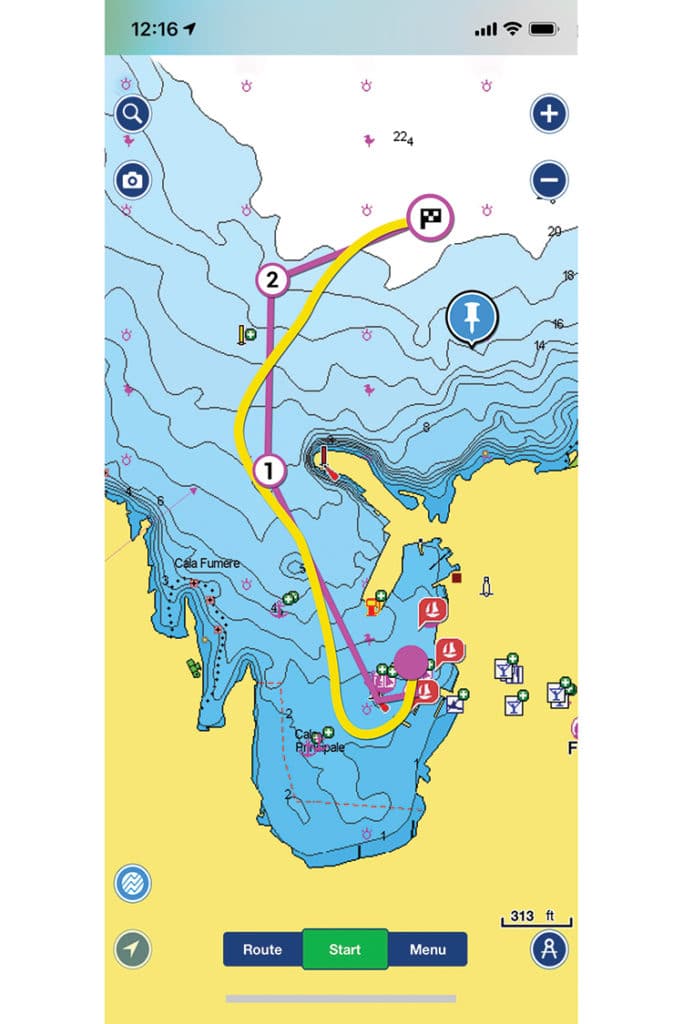

“Sailors can plan every aspect of their passage in the Navionics Boating app, then seamlessly sync their routes and waypoints to a compatible chart plotter over Wi-Fi via the Plotter Sync feature,” says Dave Dunn, Garmin’s senior director of marine sales. Garmin acquired Navionics in October 2017.

“By simply running the Navionics Boating app and connecting their mobile device to a compatible chart plotter, sailors can transfer routes and markers, update chart layers, and activate or renew their chart subscription.”

Navionics also offers daily and hourly weather forecasts, including wind and tide information, which can be used to monitor conditions; however, it’s important to understand that these forecasts cannot currently be used for weather-routing purposes. “With an active internet connection, the Navionics Boating app provides sailors with real-time weather data and GRIB files for wind forecasts via NOAA updates, but sailors who aren’t connected to the internet won’t be able to see this information,” Dunn points out. “However, sailors can still view tide and current predictions without connectivity because those are part of downloadable, offline Navionics charts.” Sailors can also download weather forecasts (out to 72 hours) for offline use, but this of course comes with the caveat that the weather can—and often does—change over that extended period of time.

“You should expect the forecast for this afternoon to be pretty reliable, but the forecast for three days from now to be less reliable, and five days from now even more unreliable,” Waters says.

Others agree. “Passage planning is really about having the best data on hand in a digestible format so you can compare the data to aid in decision-making for a safe passage,” Olson says. “One important and key feature is the PredictWind weather router, which calculates your optimal route on the PredictWind servers. This is a game-changer for low-bandwidth connections because the PredictWind Weather routing can calculate your route using all the data available over multiple atmospheric and ocean models—potentially 50 to 100 megabits of data and a billion calculations—and deliver this data into the Offshore app in a small 10-kilobit file. This also means that GRIBs are needed on board only as a visual aid to accompany the weather routes.” As anyone who has attempted to download GRIB files on a slow offshore connection knows, this can save a lot of airtime and onboard frustrations.

The bottom line for all this: Given the relatively low cost of the software-, cloud- and website-based applications discussed in this article, there’s little downside or reason not to have these capabilities on board. But, as with any new piece of technology that’s being integrated with a nav station, sailors are advised to spend time using it alongside their long-range communications equipment before casting off. Then, odds are more in their favor to enjoy a smoother, safer offshore passage, while also having access to better forecasting information while underway.

David Schmidt is CW’s electronics editor.

The Virtual Navigator

Given that this is 2021 and one’s Tesla can chauffeur them to the marina or yacht club in autopilot mode, it should come as little surprise that some of today’s navigation software can formulate a route between a home mooring and a far-flung anchorage, even in another country.

Navionics, now owned by Garmin, pioneered this technology, dubbed Dock-to-Dock Autorouting, in late 2015. As with several of the weather-routing products discussed, to take advantage of Dock-to-Dock, a boat owner will need to enter their vessel’s parameters into their Navionics Boating app ahead of time, and they are highly encouraged to manually review the auto-calculated route before committing to it.

“When planning longer bluewater passages, auto-routing might not offer much more than ETA over a given distance,” Garmin’s Dave Dunn says. “However, for near-coastal and Intracoastal Waterway passages, auto-routing offers significant advantages when paired with up-to-date charts.” This latter bit matters greatly, given the shifting nature of some seafloors; Dunn explains that Navionics releases in the ballpark of 5,000 cartography updates daily.

While Navionics is no longer the only player offering auto-routing capabilities, the addition of ActiveCaptain’s community chart layers (also now a Garmin-owned entity), which users can switch on and off, gives Navionics users other integrated advantages. Dunn advises: “Crowdsourced features such as Community Edits and ActiveCaptain Community layers are not only useful, they’re necessary. Both offer useful insight not found in any other resource or chart by way of community feedback, ratings, additional data, missing chart objects and hazards, or more-timely navigation changes that chart sources have not yet reflected.” Garmin now also allows ActiveCaptain users to upload photos. This, Dunn says, lets “other users see what dock slips, hazards, important points of interest, and other relevant local knowledge actually looks like in the wild.”

Vendor List

Expedition: expeditionmarine.com; from $1,300

FastSeas: fastseas.com; free for basic service, $60 per year for premium service

Navionics: navionics.com; free trial, then from $15 per year

PredictWind: predictwind.com; from $250 per year for weather-routing service

TimeZero: mytimezero.com; from $500