It was 0300, and I was on the helm of one of the fastest monohull racing yachts on Earth; the Bakewell-White-designed supermaxi racing yacht Rio 100. With a reef in the main, a small jib set and a large reaching gennaker unfurled, we were romping along at sustained speeds in the high teens with bursts well into the 20s. I was decked out in the latest, greatest foul-weather gear from Musto and “talking story” with a Volvo Ocean Race veteran serving as my watch captain. Pinching myself to be in this place in time, we were fully sending it across the Pacific on what was quite easily the fastest boat I’ve ever sailed on a long bluewater passage.

A multimillion-dollar, all-carbon-fiber racing yacht that has set numerous course records on the West Coast and from there to Hawaii, Rio wasn’t exactly the waterborne equivalent to a Formula One car, but she was damn close. She might not have been the lightest, nimblest, highest-tech machine on the water, but when allowed to stretch her legs for more than your typical grand prix race, she was tough to beat. A race-car analogy? How about a 1,000-horsepower, top-tier 24 Hours of Le Mans racer. That sounds right.

Taking advantage of Rio’s generous 100 feet of water-line, we were knocking out the miles en masse on our approach to California. After racing to Hawaii in the Transpac the previous summer, then stuck there for repairs, eight other souls and I were now sailing Rio home to Cali in the dead of winter so she’d be ready for upcoming regattas.

Delayed by a full day or more in the Pacific High, drifting in circles, to allow a weather system to pass in front of us, we’d then been gifted an open 1,300-nautical-mile runway to the coast in picture-perfect conditions (a distance that we would ultimately knock out in less than four days). Rio was fully coming to life, reveling in the reaching conditions and mellow following seas created by the 10 to 20 knots of northwesterly pressure that was propelling us onward. At those angles, Rio slid along quicker than the wind speed, oftentimes cruising at 15 knots in 12 knots of breeze and closer to 20 knots of boatspeed in 15 knots of pressure.

With a massive bulb keel that draws more than 21 feet when fully down, and twin rudders, the boat felt incredibly stable and very much in control when driving her in these conditions. When one got rocked up on a wave or gust, or in a puff/ wave combo, the boat heeled predictably and gave the helmsman plenty of warning before wanting to round up. When that inevitable force did come, however, a quick press of the helm to leeward was met with an instant reaction from the boat, which responded just as the helmsman intended, and oftentimes with a long, rewarding surfing run and a sharp acceleration in speed. It wasn’t the small, quick bursts of speed that a lightweight dinghy or skiff delivers, but rather the long, pronounced surfs of a massive racing yacht powering its way forward, propelled by impressive amounts of sail area and inertia.

Sailing Rio was an educational experience. I’m a pretty experienced big-boat sailor, but there are several systems and design characteristics on this behemoth that I had never seen before yet would come to understand and love by the end of the trip. One of the chief joys of sailing well-sorted racing yachts is seeing how talented boat captains and professional sailors have chosen to tackle certain problems or set up various systems.

For example, headsails are hoisted up all the way until they are resting on a halyard lock. Once the sail is on lock, a 2-to-1 hydraulic tack line pulls down on the tack until the desired “halyard tension” is achieved. The twin-wheel, dual-rudder steering system is a magnificent array of foils, steering wheels, Spectra cables and sheaves and, finally, carbon-fiber tie rods and track-and-car assemblies in the hull.

At first glance everything seemed complex, but once broken down bit by bit, there’s a theme of simple, robust, effective systems in place throughout the yacht. While some of them are indisputably complicated (and no boat is ever perfect), I’ve been on boats about half the size of Rio that were at times more frustrating and laborious to sail and maneuver. With the larger headsails hanked onto the forestay (I’ve never been a huge fan of head foils) and the smaller ones on furlers, keeping Rio in phase with the conditions was a fun and relatively straightforward process, even with a somewhat shorthanded crew.

Much of the credit for the relatively smooth sailing was boat captain and skipper Keith Kilpatrick, another Volvo Ocean Race veteran who has “been there and done that” everywhere in the world of yacht racing. Intimately familiar with Rio and her systems, Kilpatrick had assembled a group of old-school sailing pros, friends and crewmates who he’s known for decades, and thrown in a few talented “young guns” who were experienced, up to the challenge and keen to knock out some miles. Needless to say, I was beyond stoked to have earned a spot in “Kilpatrick’s Navy” for a couple of weeks. The sailing was fast, the food tasty, and while we were all focused on the job at hand, the vibe on board was decidedly relaxed and fun.

A little history: When computer-technology magnate and passionate racing sailor Manouch Moshayedi, Rio’s owner, set out to win the coveted Transpac “Barn Door” trophy for first-to-finish-line honors in 2015, he knew he needed a unique yacht. At the time, the Barn Door rules required a monohull to have human-powered winches and hydraulics, and conventional ballast (i.e., a fixed keel and no water ballast), so he couldn’t merely show up with any of the mammoth supermaxis such as those that competed in races like the classic Sydney-Hobart, many of which had canting keels and water ballast, and powered winches. (The Transpac rules have since been relaxed to allow canting keels.)

So when Moshayedi put the program together, he looked to purchase or build a fixed-keel supermaxi with no water ballast and all human-powered winches and hydraulics. After consulting with many top international sailors, the decision was made to buy the 98-foot Lahana and have the Kiwi design consortium of Bakewell-White redesign the boat for a full transformation, which would take place at the Cookson yard in New Zealand.

The old water ballast was removed by cutting off the back half of the hull, which was replaced by a new, wider stern section that now sported the twin rudders. With the loss of the water ballast, the designers would need to rely on enhanced hull-form stability to keep Rio on her toes in fast power-reaching and running conditions.

She was further turbocharged by adding a longer boom and longer bowsprit to facilitate a larger mainsail and bigger spinnakers. With the input from two-time Volvo winner and three-time America’s Cup vet Mike Sanderson of Doyle Sails New Zealand, the boat underwent an extensive sail program that would ultimately reap huge performance gains on the water. Combine the added horsepower and righting moment with a weight savings of somewhere between 6 and 7 tons, and the Rio 100 that emerged from the shed was an entirely different beast than the old Lahana that had entered it.

On the water, the boat immediately proved her merit in hard offshore racing in New Zealand and Australia. After her training and adventures Down Under had concluded, Rio 100 was shipped to California, where she began an ambitious few years of Pacific Ocean campaigning.

In her first two Transpac races, in 2015 and 2017, Rio indeed claimed the Barn Door Trophy, though she failed to come up with the type of performance that would make the boat truly legendary. Rio 100′s crew saved that performance for the 2016 Pacific Cup race. In a record-setting El Niño-affected summer, the North Pacific was bursting with hurricane and cyclonic activity for the duration of the season. It was a navigator’s nightmare, in which many of the competitors (including this writer, aboard a Swan 42) finished in the middle of named tropical storms that were uncharacteristically battering the island of Oahu.

As well as the storms, the race was epic because of a nuking breeze almost all the way across the course, with a large broad-reaching racetrack that was set forth before Rio and the fleet. Maintaining a starboard jibe almost the whole way, Rio’s crew set their reaching spinnaker and smashed their way to Hawaii, knocking some two hours off the already impressive course record set by the 40-foot-longer Mari Cha IV in 2004. Finishing the 2,070-nautical-mile race in just 5 days, 3 hours, 41 minutes, Rio 100 claimed an outright course record in the “other” big Hawaii race.

I got my invite to do the Rio delivery in the midst of my studies at Hawaii Pacific University. Of course, there was no way I could take time off to cross the Pacific in the middle of a semester. Or could I? After all, it was a supermaxi. I immediately realized that if I let the opportunity pass, I’d regret it forever. I said yes, informed my professors I was leaving for a bit, and packed my sea bag. In hindsight, it was the best decision I’d made all semester. I blame it all on Rio.

After a false start in which our crew collectively realized that the old laminate racing mainsail provided to us was doomed to failure, we reappropriated it to the nearest dumpster and had the current racing mainsail shipped in. From the moment we started our second attempt at the delivery, things could not have gone better. The night before leaving, we departed Honolulu’s Ala Wai harbor on a high tide to bend the mainsail on and attach it to the many luff cars that slide up and down the mast—not a simple task on a 100-footer. With another crewmate, I was hoisted about 15 feet above deck to hook up the massive sail’s square-top section with its huge gaff batten and two headboard cars; soon enough, we were joined by two humpback whales. In the thick of their annual winter stopover in the islands, the pair of whales swam alongside and seemed to watch over us and wish us a safe passage from Hawaii. Fifteen feet up the mast, on a calm full-moon night in the tropics, with whales alongside, I had the first of many magical “pinch myself” moments of the trip.

We left Honolulu the following day. In contrast to the normal pounding that one takes when close-reaching north away from the islands, we were granted a very gentle escape. With easy conditions that allowed us all to gain our sea legs before the rough stuff, we saw the gentle trades gradually replaced by reinforced winds that would carry us north. Day after day, the breeze continued blowing as Rio knocked off miles under heavily reduced sail. Even throttled all the way back in an effort not to damage the boat, we still managed double-digit speeds most of the way, while attempting not to slam the boat too hard. With an extra-long flat-bottomed vessel, there is an unusual—and somewhat disconcerting at first—sensation each time the boat slams hard upwind. As skipper Kilpatrick described it, “We’re effectively on a 100-foot-long teeter-totter.” When driving, you’re standing some 40 or 50 feet behind the keel—and the origin of the reverberating motion—and can literally feel the boat moving up and down in a fashion unfamiliar to anyone who hasn’t sailed a boat of this length.

As the breeze finally abated and we entered the Pacific High, we were able to shed a couple of layers for the first time in days. Advised by the weather routers to stall in the high for a day or more to avoid 40 knots of breeze along the coast, we effectively shut down everything and commenced our halfway party. A few repairs here, a beer or two there and a live ukulele concert by one of the crew was the perfect way to break up a wintertime delivery across the Pacific.

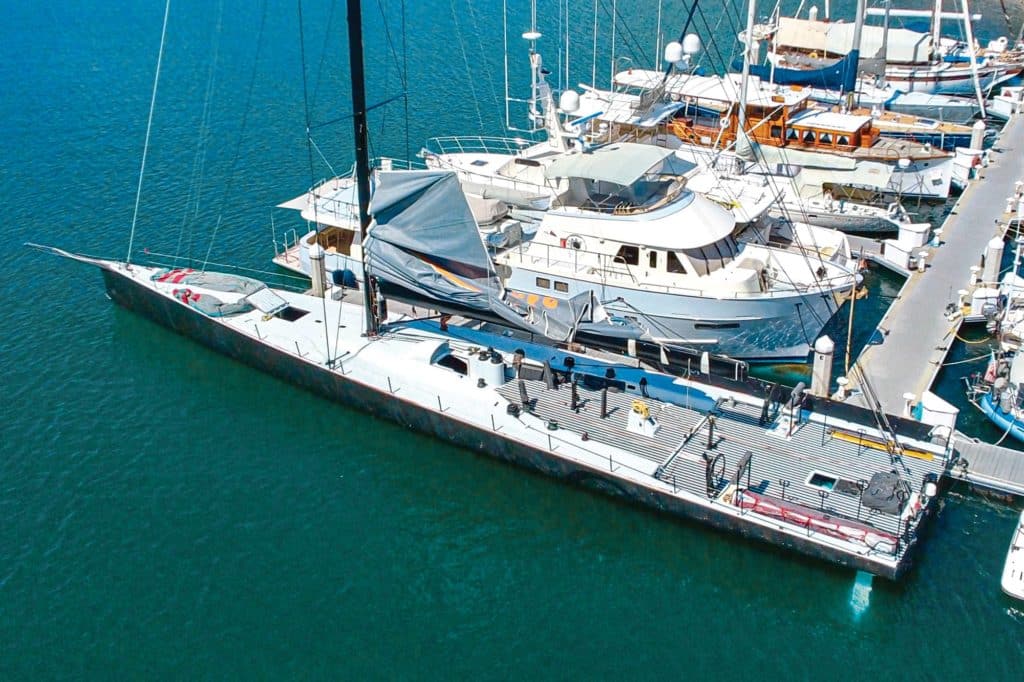

Back into the breeze we eventually went. On our four-day-long glory run back to the California coast, we began knocking out miles toward the mark in wholesale fashion, three-sail reaching toward the coast. Flying toward Cali with plenty of fuel left on board, we sailed ourselves out of the breeze about 100 miles off the coast and motored toward our eventual destination of San Diego, arriving at Driscoll’s Boat Works in Mission Bay in the dark of night. On a crisp, clear winter evening, we tied up Rio, stepped off, and reveled in that special moment that comes with the conclusion of any big adventure or ocean crossing. We had made it.

The dash across the Pacific was likely the only time I’ll ever sail the boat, and it was an experience that I will cherish forever. Soon enough, I was back in class. Daydreaming of Rio.

Ronnie Simpson, his studies concluded, is currently based in Fiji, having recently returned from—what else?—a delivery to Hawaii. A contributing editor to Cruising World, he’s used his college degree wisely, carving out a career sailing, writing and doing media work for major yacht races.