When I was new to sailing many years ago, it didn’t take long for me to realize that it was much better to anchor securely the first time rather than to be stumbling on deck at 0300 on a blustery, rainy, pitch-black night, trying to haul-in and then reset a dragging anchor. Anchoring is a vital part of seamanship. It’s just as important to be able to stop a boat as it is to make it move, and while different boats react differently when anchored, there are still some common tenets that apply to all anchoring situations. The main worry is always that the anchor will uproot, for whatever reason, and the boat will drag, sometimes with catastrophic results.

The best assurance to avoid dragging is to lay a good length of rode, about five or six times the anchoring depth for all-chain (the rode being the total length from the boat to the anchor). But this in itself doesn’t guarantee that an anchor won’t drag, and after hauling in 200 or so feet of chain, when dragging in 40 feet—all in the above-mentioned weather conditions—most people soon learn to do it right the first time.

RELATED: Attend to your Anchor

A primary objective is to get the chain and anchor to lie flat along the bottom, where the anchor has the best chance of scooping its way into the seafloor. This is the reason for using a heavy chain with a good catenary. In especially deep anchorages, even a long rode will tend to straighten out and lift, with a chance that the anchor will break free. An age-old method to minimize this is to weight the chain about halfway along its length with what is generically called a kellet—a heavy weight with a pulley attached that enables it to slide down a chain and line, thereby helping to keep the rode flat on the bottom. Such a device has no actual gripping capability, so even if it touches the bottom, it will not add to the actual holding ability of the anchor. A kellet is also devilishly difficult to store on a small boat, being both heavy and unwieldy. However, using a second anchor instead of a simple weight would help the main anchor, provided it could dig itself into the bottom as well. But how does one achieve this idyllic state?

After much trial and error, I devised a simple method, using a second anchor attached to the main rode, which has proved to be drag-free, even in the most severe conditions.

Before explaining the method, I must say that I firmly believe that any main anchor should be as heavy as the anchor crew or windlass can reasonably handle, irrespective of boat size—within reason, of course. It is possible that the spate of different-shaped anchors that have appeared over recent years don’t need to be as heavy as the old styles, but for me, heavier will always be better. An all-chain rode is likewise better than a chain-and-line combination, if only because of the extra weight. Another factor that can cause dragging is windage, and my schooner, Britannia, has plenty of this, with two masts, three roller-furled sails, a square-sail yard (Britannia is a brigantine) and a large cockpit Bimini. She also weighs about 22 tons.

The boat has two CQR anchors on rollers, on either side of the bowsprit. The main anchor is a 60-pounder, and the other weighs 35 pounds. I actually wish I had two 60-pounders, this weight being the heaviest I can handle safely. The 60-pounder is on 250 feet of 3⁄8-inch chain, with a further 200 feet of 5⁄8-inch line for deep anchorages. The smaller anchor has a rope bridle attached to it, which I hook up to the main anchor when deploying my system.

The bridle is simplicity itself: a short length of strong rope, two thimbles and a couple of shackles. I made it using a 5⁄8-inch diameter line, with stainless thimbles spliced and whipped on each end. One end remains permanently shackled to the stock of the 35-pound CQR, then passes around the underside of the bowsprit and bobstay, and up the roller of the main anchor on the other side of the bowsprit, where it’s made fast when not in use. The bridle is 7 feet long on my boat; it will vary in length depending on your own bow layout, but the idea is to make it as short as possible. Boats without a sprit and only one easy-to-reach bow roller can have a very short bridle.

Having set up this simple arrangement, here’s how I anchor every single time for an overnight stay, without exception, irrespective of the weather forecast.

After letting go the main anchor and paying out about three times the depth, I allow the boat to fall back with the wind or drive it back with the engine until it feels as though the anchor has begun to hold. I shackle the rope bridle to the chain, the other end still being attached to the shank of the second anchor. I then attach a length of strong line to the shank of the second anchor, which of course needs to be at least as long as however much chain I finally intend to pay out.

The second anchor is then released from its roller, where it hangs by the bridle on the chain. I back the boat and pay out more chain, usually about two or three times the depth. When this lot is settled on the bottom, a hefty burst on the engine will drag both anchors along and hopefully bed them both. At the same time, the rope attached to the second anchor can also be used to gently snub in this anchor.

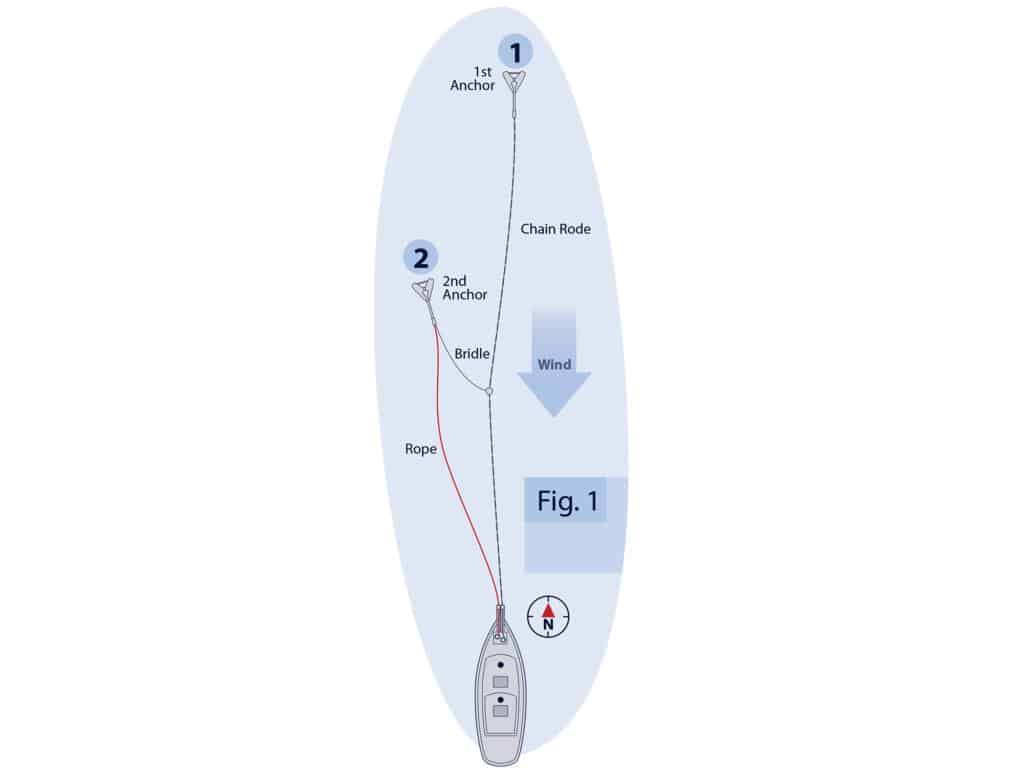

I now have the heavy main anchor dug in at the head of a good length of chain with the second anchor attached to it, and hopefully also bedded in with another length of chain and line up to the boat (Fig. 1). This gives a total of 95 pounds of anchors, complemented by a load of heavy chain. Is there any wonder we never drag?

All this might sound a bit of a rigmarole to deploy, but it’s really quite easy when organized properly beforehand. I can anchor using this method almost as quickly as any boat using a single anchor but with a good deal more peace of mind if the wind pipes up. This anchoring method can be adapted to any boat with two anchors—and who doesn’t have two anchors on their boat?

There are definitely benefits in making the effort: If for any reason (wind or tide) the pull on the boat becomes strong enough (always at around 0300, of course), the rode will straighten until the bridle becomes tight and begins to lift the second anchor. If this was well-set, it will resist the chain trying to lift it off the bottom, dampen the effect of whatever is causing the rode to tighten, and ensure the remaining chain leading to the main anchor remains flat on the bottom.

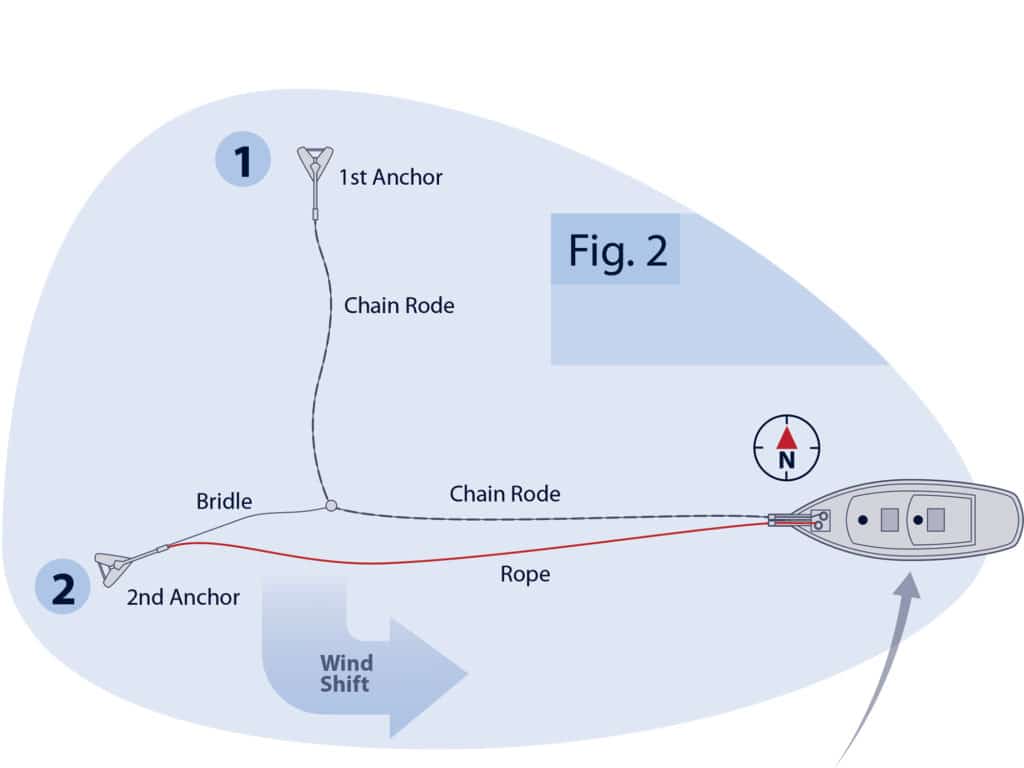

If the wind shifts or the tide turns, the boat will initially swing to the second anchor (Fig. 2). If the wind or current is so strong that it drags the chain around and dislodges the second anchor, it will invariably dig in again. If it refuses to do so, the whole rode will eventually straighten out in the new direction and the boat will lie to the main anchor, and probably also the second. This has never happened, and we have often found ourselves in the morning lying to the second, smaller anchor yet with the confidence of knowing there is also a load of chain in advance of it, with a whopping great anchor also bedded in.

Weighing anchor is only slightly more tedious than doing so with a single anchor on chain, with or without a windlass. The chain and line are hauled up until the second anchor appears on its bridle, where it can be hauled over its bow roller using the line attached to its stock, and then secured. The bridle can then be unshackled from the chain and the end secured back to where it normally sits. At this point, the boat is still secure on the first anchor, and I usually take a breather. The main anchor is then brought up in a normal manner.

For me, the main point of doing all this is simple: The system has never dragged on Britannia, or any other boat on which I have ever employed it. There are other benefits apart from a drag-proof mooring: In rough conditions, it is comforting to know that you are lying to two anchors and also have a sturdy line attached to the second anchor as a backup.

RELATED: Anchor Like a Pro

It is much easier and quicker to set my system instead of laying two separate anchors at, say, 45 degrees. There is no maneuvering to be done as there is when trying to lay two anchors in different locations, and no chance of their rodes tangling if the boat swings.

By way of an epilogue, I can recount a true story. We were once anchored by my method in Cala Portinatx, a beautiful rocky cove in northern Ibiza, in the Mediterranean’s Balearic Islands. A mistral had been forecast, but it arrived in the night much stronger than anticipated, and the cove was soon awash with boats dragging their anchors and heading for the rocky shore, along with the associated mayhem—but not us. My only concern was keeping watch in case other boats crashed into us. One small boat drifted up to us, the exhausted occupants unable to reset their anchor or motor against the wind. I heaved them a line and attached it to our aft cleats as they drifted astern. Then a second boat scudded by, and I passed them a line likewise. All three of us remained like this during a very blustery night during which a substantial motorcruiser was driven up a sandy beach by the frantic occupants—which was certainly a novel way to anchor. Two boats were completely wrecked on rocks, and one person lost his life.

It is certainly worth anchoring well, even in a flat-calm and a good forecast, because old Neptune is well-known for frequently changing his mind.

DIY warrior Roger Hughes frequently writes for CW about his upgrade projects aboard his schooner, Britannia.