Antifreeze is a critical component in any liquid-cooled internal combustion engine that relies on a closed cooling system. It should be referred to as “coolant” because it does much more than prevent freezing.

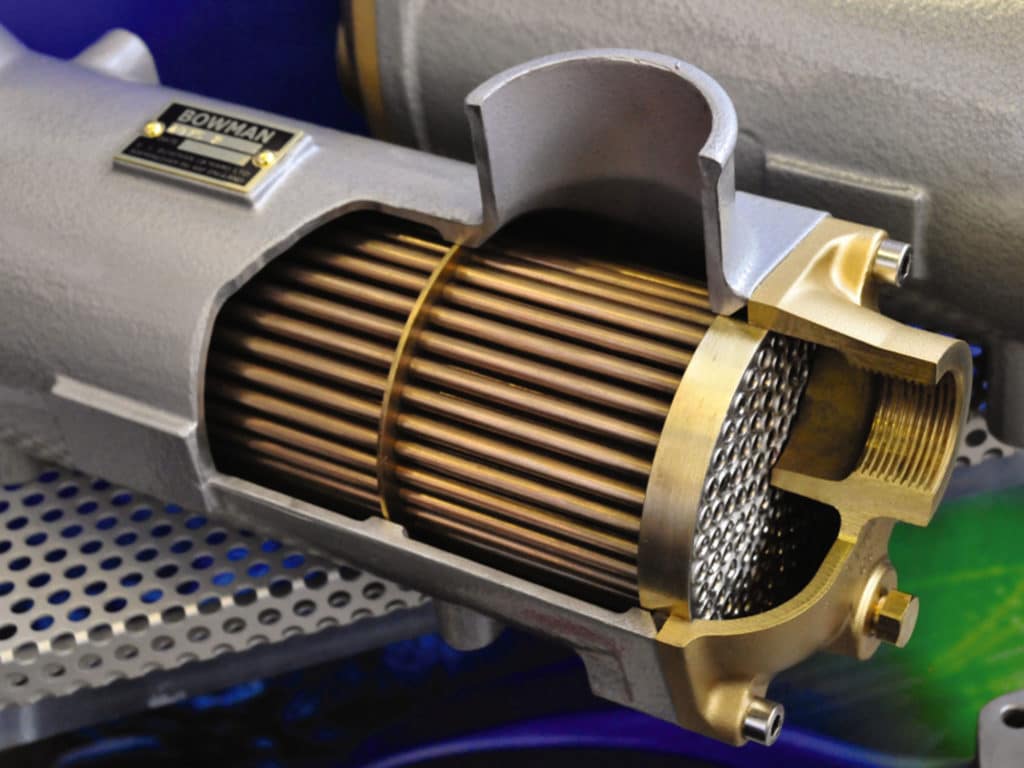

In a closed cooling system, excess heat created by the engine is absorbed by the coolant and transferred, via a heat exchanger, to seawater and pumped overboard with the exhaust gases. From the 1930s through the 1990s, nearly all coolant used in applications like this was the familiar green ethylene glycol (referred to as IAT, or inorganic acid technology), which provided corrosion protection and circulator-pump lubrication, offered freeze prevention down to about minus 30 degrees Fahrenheit when mixed at a 50-50 ratio with water, and elevated the boiling point about 15 degrees Fahrenheit above that of ordinary water. Pressurized cooling systems, such as those on all modern diesel engines, also raise the boiling point; at 15 psi, the boiling point of ordinary water is 250 degrees Fahrenheit.

Today things are different, mostly in the realm of choice; there is a range of coolants from which to choose, including organic acid technology (OAT), hybrid organic acid technology (HOAT) and nitrided organic acid technology (NOAT), along with some proprietary coolants designed for specific engines. These formulations afford engines greater corrosion protection and longer coolant life. Then there’s color: In addition to green, there is blue, pink, orange and red, and while those colors might be indicative of a particular chemistry, it’s no guarantee.

Always follow the coolant instructions provided by your engine’s manufacturer, and never add coolant without knowing what’s there already. In an emergency, you are better off adding water (preferably distilled, but anything will do in a crisis) than the incorrect coolant. The primary mission of coolant is to prevent freezing, but if that’s not an issue, water will work just fine short-term.

When changing coolant, whether to a similar or different chemistry, plan on flushing the system to remove sediment and all traces of old coolant. Remember, conventional ethylene glycol is poisonous, so don’t leave uncovered containers out where they can be accessed by pets or children, and always clean up spills (it evaporates very slowly), and dispose of old coolant properly.

If you’ve decided to replace your coolant, you should once again do so in accordance with engine-manufacturer guidelines, and in the absence of those, about every 1,000 hours or three years. Unless the manufacturer specifies one of the above-mentioned more-modern varieties, most sail auxiliaries and gensets can use conventional IAT; however, it should be formulated for diesel-engine use.

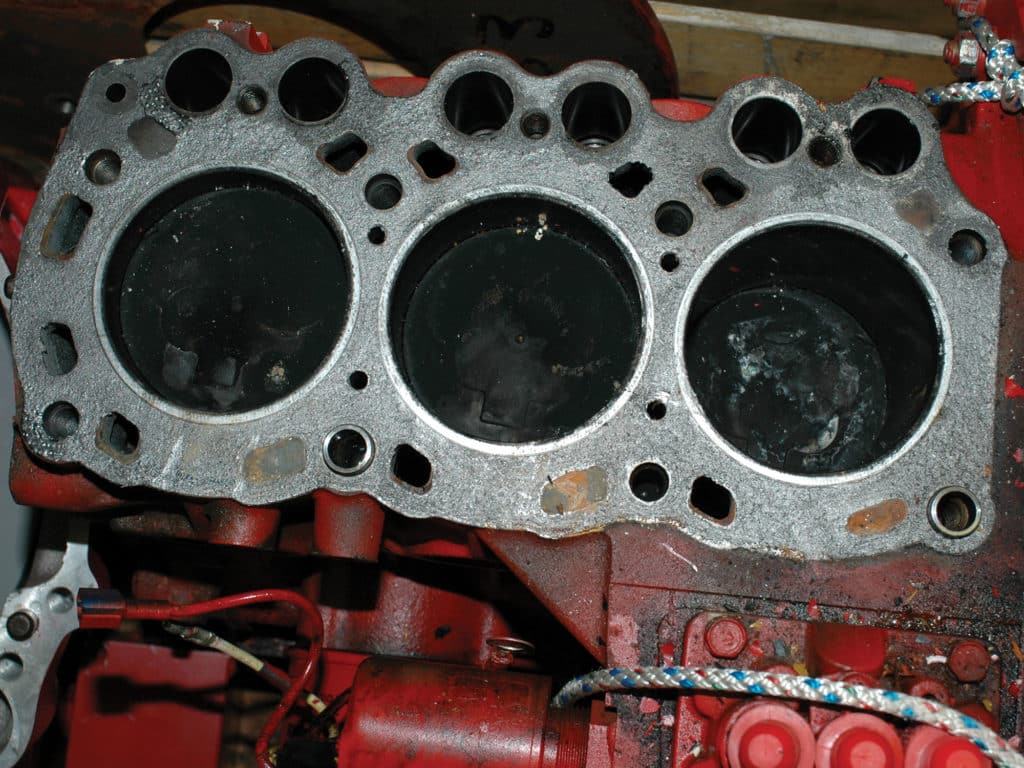

Diesel engines, particularly those that rely on a “wet” cylinder—wherein the outside wall of each engine-cylinder liner is in direct contact with the coolant—can experience a phenomenon known as cavitation erosion, sometimes called ringing. At each power stroke, the cylinder bulges slightly and then rapidly contracts, creating a void or cavitation bubble that implodes violently, and in doing so, removes some metal from the liner. This all occurs on a microscopic basis and takes time for damage to occur, but after enough time passes, it can lead to cylinder-liner leakage and failure. This is rare on sailboat auxiliaries, but why risk it? By using a high-quality diesel-rated coolant (these include anti-cavitation additives), and changing it regularly, you will all but eliminate this possibility. Supplemental anti-cavitation additives are also available, and these can be added on an annual or hours-based model.

If you are using a concentrate (that is, a coolant that requires the addition of water as opposed to one preformulated), be sure to mix with distilled water only. Do not use tap or bottled water. Water that contains minerals can leave scale deposits within the cooling system, thereby impeding heat transfer. Unless otherwise instructed by the manufacturer, the mix ratio should be 50-50 for the best balance of corrosion, freeze and boil protection, as well as heat transfer (pure distilled water can transfer more heat than coolant, which is why it’s undesirable to increase the coolant-to-water ratio beyond 50 percent). Anything under a 30 percent ratio of coolant can allow biological growth to form within the cooling system, especially on engines that are used infrequently. So stick with the 50-50 ratio for the best results.

RELATED: Sailboat Diesel Engine Analysis

Finally, if you’ve never checked the coolant concentration in your engine, you should do so, especially before winter layup. If the coolant concentration is too low, it will freeze, which could cause significant and possibly irreparable damage to the engine. While the “floating balls” test tool works for ethylene glycol, a refractometer is more accurate, and it’s applicable to all coolant types.

Steve D’Antonio offers services for boat owners and buyers through Steve D’Antonio Marine Consulting.