As with most popular chartering destinations, sailing the San Juan Islands tests the navigation skills of a visiting sailor, while at the same time providing for a memorable getaway with family and friends. The trick is to arrive in new cruising grounds with a fair understanding of what you’ll find when you get there.

Using the Pacific Northwest as an example, it’s easy, with chart in hand or called up on a tablet screen, to recognize the spectacular features of the area. And the best way to put Puget Sound and the Salish Sea in perspective and begin planning a trip there is with a wide-angle (small-scale) view of the entire region. Use the chart in combination with detailed descriptions in the Coast Pilot and numerous cruising guides to develop an overall perspective. So, regardless of whether you sail or fly to this remote destination, you’ll arrive with an awareness of its cruising bounty.

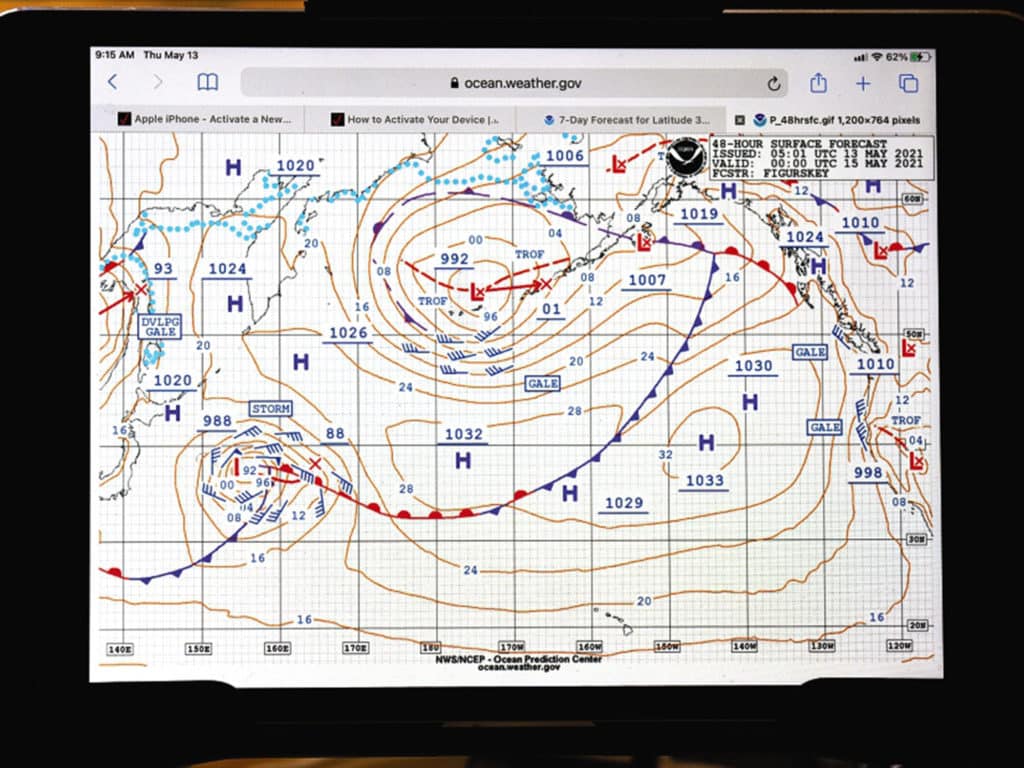

While doing this pre-charter planning—or when preparing to sail your own boat to a new destination, for that matter—factor in the time of the year and look closely at how the seasons change. Check the percentage of gales and calms called out on traditional pilot charts and in contemporary climate-model data. Download weather maps produced and archived by the Ocean Prediction Center (ocean.weather.gov). Note the similarities and differences between your local sailing conditions and what you’ll find in the San Juans. Details such as an awareness of the tidal range, its impact on currents and the local aids to navigation are important. You’ll know you’ve done enough homework if your first cruise in the Pacific Northwest makes you feel as though you’ve been there before. This level of situational awareness helps to minimize surprises.

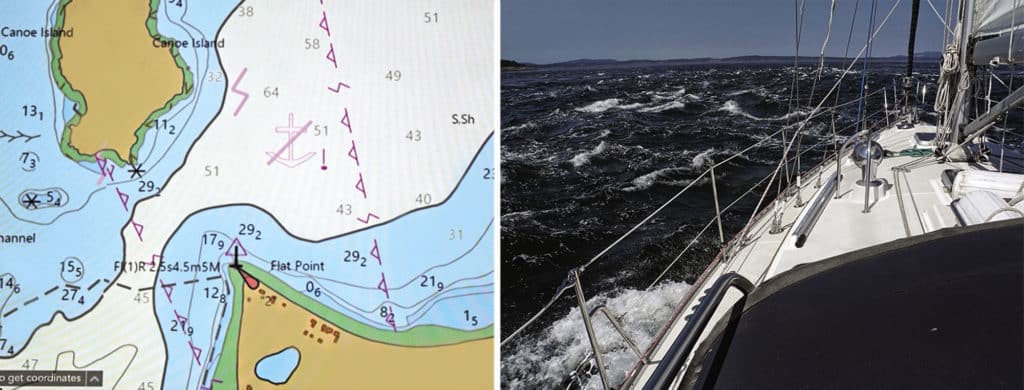

For example, each meteorological mood shift results in a change in sea state, especially in the tight passes between islands and in semiprotected anchorages. Be ready for the effect that spring tides have on surface currents, especially when bolstered by winds in sync with the set and drift of the current. It pays to refer to a current table or a digital current display when planning each day’s route. The bottom line when you’re sailing unfamiliar waters and approaching a new anchorage or marina is to envision the challenges, mentally rehearse your approach, and don’t let strong currents and a large tidal range go unnoticed.

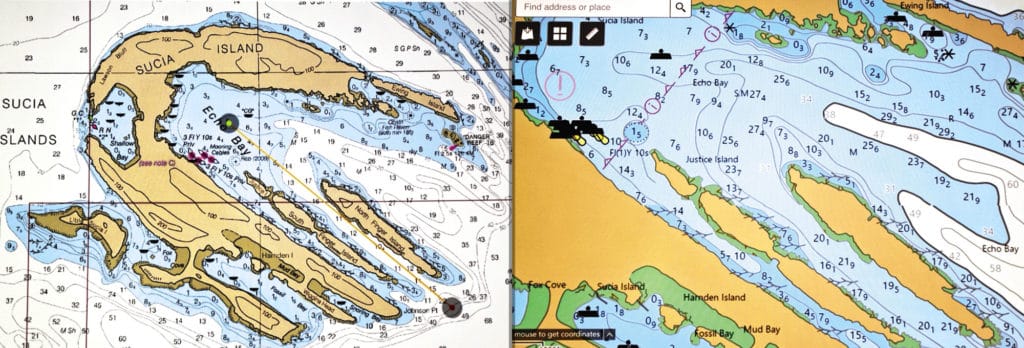

I prefer to have alternate anchorages in the game plan, and the one finally chosen usually has as much to do with tomorrow morning’s weather as it does with the conditions of the moment. For example, in the charts depicting Sucia Islands and the Echo Bay anchorage (above), I liked the mud bottom and ample swinging room, but I would have gone elsewhere if the forecast had indicated SE winds of 15 to 20 knots or more. It’s no fun having to bail out of a good anchorage gone bad. It’s even worse when it happens in the middle of the night in unfamiliar waters. So make the choice on where to drop the hook with tomorrow’s weather in mind, not just current conditions.

Chartering out of Anacortes or Bellingham puts you in the heart of the San Juan Islands. Arrival at a charter company’s home base usually mixes boat familiarization with resortlike excitement. Make sure you don’t miss out on the valuable local knowledge conveyed during the briefing. Whenever an experienced local sailor starts pointing to destinations on a chart and detailing the local cruising grounds, I pay close attention. His or her overview and recommendations about local highlights and places to avoid should be noted. If you’ve done the right homework, it probably sounds familiar. Jot down what comes as a big surprise, and later on determine how and why you missed it in your pre-arrival charter planning.

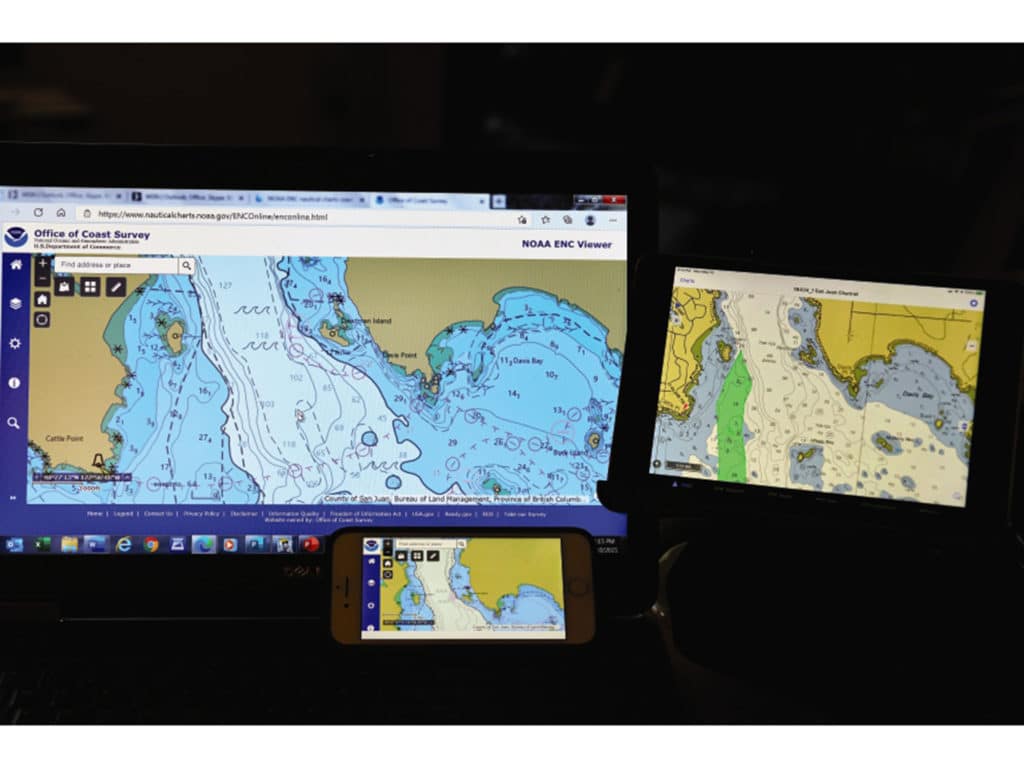

I prefer to show up with a tentative itinerary compiled ahead of time. It’s based on crew input and individual sailing interests overlaid on the destination’s features. Often, the same charter region holds appeal to cruising bird-watchers as well as bar-hoppers. If you’re into both, it’s all good; if not, you’ll want to fine-tune your route according to preferred activities. The easiest alternative is the migration from one mooring area or slip to another, where one good restaurant leads to the next—not a bad fate for those out to relax and saunter among the islands. But, the more you want to stray from the pack, the more decision-making about anchorage appropriateness and route planning you shoulder. Detailed charts become more and more vital. That’s another reason to show up with all the digital charts for the area embedded in a nav program on a laptop, tablet or smartphone that’s as familiar to you as the deck layout of your own boat.

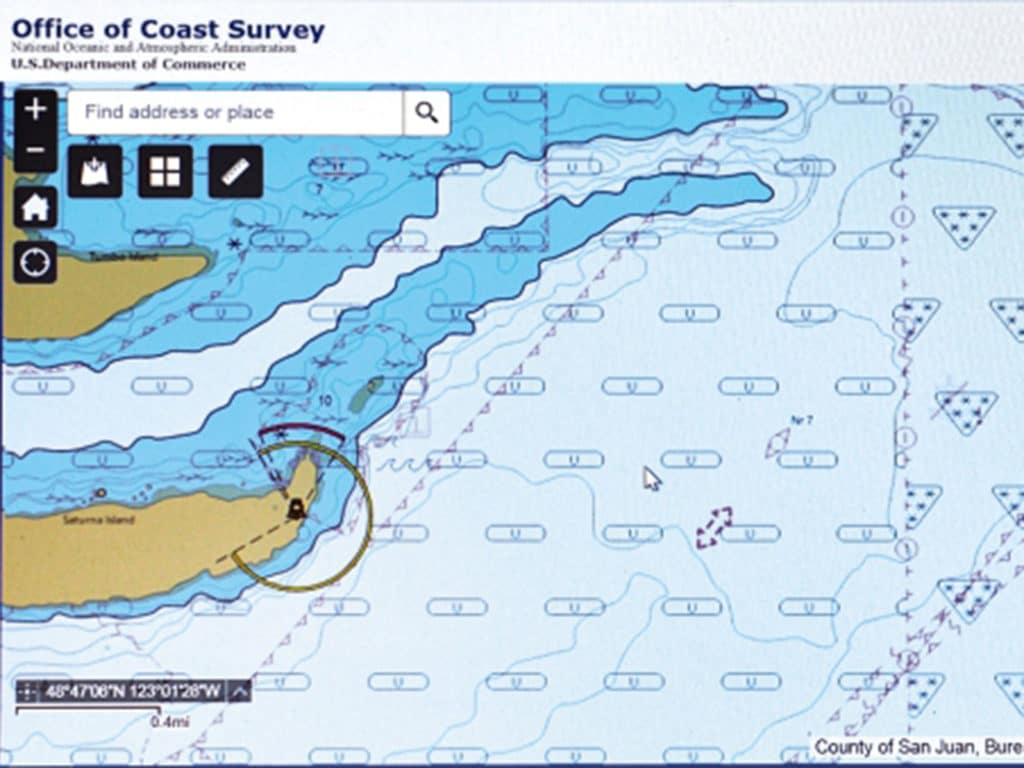

It’s important to keep in mind that these detailed, large-scale charts have some internal variations in accuracy. And every navigator should have the answer to two key questions: What’s the indicated Zone of Confidence ascribed to my location on the chart? And what does the “satellites” page on my GPS receiver indicate about the Horizontal Dilution of Precision? These two factors have a major influence on the GPS/digital chart’s accuracy, and are most often the culprit when the cursor on your multifunction display screen and your location aren’t one in the same.

HDOP is used to describe the relative position of navigation satellites, which affects a plotter’s accuracy. A low HDOP value represents more accuracy; a high number, less.

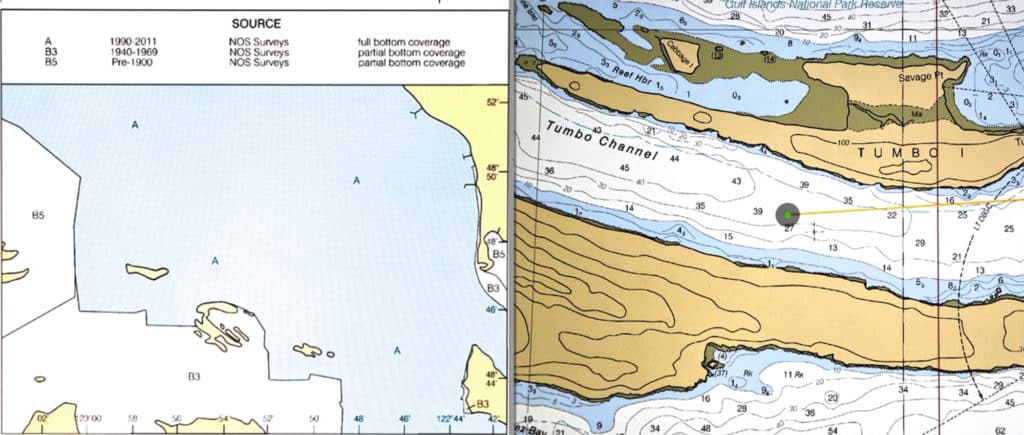

One of the benefits of NOAA’s new electronic navigational charts is a switch from their old Source Diagram descriptions of survey accuracy to a more user friendly, internationally used ZOC reference block. These inserts on large-scale charts tell chart users when certain parts of a given chart were last surveyed and what anomalies might be encountered. This lack of recent survey data comes as a big surprise to many mariners. For example, detailed charts of many coastal water bodies include large areas labeled in the Source Diagram as B3 and B5 (equivalent to ZOC “C” and “D” designations on an ENC). This indicates that the most recent survey data was pre-1949 and pre-1900, respectively, with position inaccuracy of up to plus or minus 1,600 feet for C and worse than that for D. This means that even with excellent GPS signal strength, an abundance of available satellites and minimal HDOP, your boat could be over a quarter-mile away from where it appears on the digital chart. (On the other hand, ZOC category A1 designates an accuracy of plus or minus 16 feet.)

These incongruencies in chart accuracy are explained by NOAA and all other national cartography sources as a manifestation of their primary mission. They provide charts for commercial maritime navigation. Most major, well-marked channels and waters leading to larger port facilities have an A1 or A2 ZOC designation, based on both depth and positional accuracy. Cruisers often favor more off-the-beaten-path parts of a waterway, where surveys have not been a priority and greater variations in chart accuracy exist.

NOAA’s Coastal Survey is putting new technology to work, and in 2025, the new ENCs will show another leap forward in accuracy and detail. Third-party chart development by companies such as Navionics, C-Map, etc., are making great inroads by adding detail to those uncharted waters, and their collaboration with NOAA holds promise for sailors cruising among the shoals and exploring skinny waters.

In the meantime, put your fathometer and radar to use when navigating in regions such as among the San Juan Islands. Their steep, rocky slopes and abundance of beacons, towers, and other charted land-based structures send a crisp return signal that can create an effective radar overlay. Comparing the relationship between the cartography and the radar signals helps confirm location accuracy. It’s also helpful to confirm chart soundings with your depth sounder. Make sure to factor in the tidal range’s influence on the depth readings.

Still, even with the challenges, it’s hard to top the rewards of a sailing vacation. As with the landfalls in the Caribbean, the Med and the vast Pacific, the islands of the Pacific Northwest provide a challenging navigation curriculum, and the campus for that training can’t be beat.

Ralph Naranjo is a circumnavigator, technical writer, former Vanderstar Chair at the US Naval Academy, and author of The Art of Seamanship, among other books.

The Charts, They Are A-Changin’

Sailors from Capt. Cook to Capt. Ron have extolled the value of cartography—and today we have better options than ever before. Most nautical charts, whether digital or paper, are Mercator projections that show latitude and longitude in a perpendicular, girded relationship. This simplifies plotting, handling headings, bearings and distance measurements.

Digital vector charts—designated as electronic navigational charts by NOAA and other third-party sources—are taking precedence over the venerable old standby: the raster navigational chart. The latter is a pixelated rendition of NOAA’s paper charts, and many sailors favor its familiar look and symbology. But raster-based NOAA charts are headed to the locker labeled “lead lines, RDFs and Loran-C units.” Fortunately, much of the symbology remains consistent between RNCs and ENCs. They might look a bit different, but the latter’s seamless zooming ability involves adding layers of detail, not simply magnifying a fixed picture.