If we end up on the rocks, we stay on the boat. OK?” The storm arrived so suddenly, and was so fierce and unexpected, it took not only our anchorage by complete surprise, but much of southern Spain, and later, after sweeping through the region, would have local news stations claiming it to be “a storm unlike any in living memory.”

The following details the experience and our individual perspectives on the most violent wind to cross our decks in 13 years and 48,000 nautical miles of world cruising, and how, by working together, and with a little help from Dream Time, our Cabo Rico 38, we survived without injury or damage.

Neville: Our 254-nautical-mile passage west, tracing latitude 39 from Sardinia, Italy, to the Balearic Islands, was a cruising delight, and after 53 hours of gliding across a smooth Mediterranean Sea, carried softly by 10 knots of northerly breeze beneath a deep cerulean sky, we raised the Spanish island of Majorca, and with it our 26th courtesy flag since leaving New York in 2007.

We anchored Dream Time in a pretty bay framed by rock and a sandy beach off the southern coast, dropping the hook in 15 feet of translucent water off the small village of Colònia Sant Jordi. Holding proved poor, with a deceptive layer of thin white sand concealing slabs of rock—seabed conditions that, ironically, had us comparing it to an anchorage in Belize, when 11 years earlier and just one year into our world voyage, Dream Time’s two anchors clung desperately to limestone bedrock in 65 knots of wind during Tropical Storm Arthur. But exploring with mask and snorkel, we discovered an area offering slightly better purchase, and dropped our 60-pound CQR with 90 feet of chain before setting the hook. By late afternoon we were at rest, happy to be anchored and ready for the shared, peaceful sleep that comes after an offshore passage.

We had timed our arrival carefully because forecasts were predicting squalls and wind gusts to 25 knots the following day. We awoke to a calm, humid morning with heavy skies that promised rain. But we felt safe, and after zipping up the cockpit canopies and checking our position with the dozen or so boats anchored in the bay, we settled in for a cozy day of reading.

Around noon, when a light rain began to fall, Catherine absentmindedly murmured the old sailor’s warning from behind her magazine, “Rain before wind, reef it in.” Just 15 minutes later, her premonition proved horrifyingly accurate.

Catherine: At 1230, a dramatic wind shift from northeast to southwest swung Dream Time 180 degrees, and we both went up to the cockpit to see what was happening. The sky had turned an ominous black and the rain suddenly became very heavy, then in what seemed like a second, the wind rose to 30 knots. We started the engine, and Neville quickly ran forward to stow the bow canopy we had rigged over our cutter boom. Minutes later, the wind went from 30 to 60, and then to a jarring 70 knots, and the rain, which was now torrential and blindingly horizontal, reduced our visibility to zero.

We put on life jackets just in time for the cockpit canopy to tear away. Neville had to race to take down all the remaining canvas before the wind turned them into deadly whips, and I took the helm—running the engine in gear in an attempt to reduce the load on our ground tackle. The dinghy, which we had hoisted and secured alongside, was now flogging and crashing into the freeboard, but there was nothing we could do about it.

It was all happening so fast, I could hardly figure out who was moving: us or them? Who was dragging? The GPS was our only point of reference.

With no visibility, we could only watch in horror as boats appeared and then disappeared again into the torrential fog. A large Beneteau that had been anchored beside us was heeling hard over, beam to the wind and fighting for its life. A powerboat swayed and swung, motoring wildly among the boats trying to re-anchor. It was all happening so fast, I could hardly figure out who was moving: us or them? Who was dragging? The GPS was our only point of reference, but with the dramatic wind shift, even that wasn’t clear.

Somehow in the middle of all the noise and chaos, we both heard a loud jarring thud somewhere forward. I went below and could hear a slow steady chain sound but couldn’t figure out what was happening, so I came back up and told Neville, who asked me to take the helm while he went forward on deck.

He came back to report the snubber hook had bent and fallen away, and that 300 feet of chain had paid out. Somehow he needed to attach another snubber on the last remaining links to hold us. He reached behind me to grab his diving mask, and for a terrifying moment I thought he was going to get in the water. I yelled, “You are not going in!” He looked at me confused and smiled. “I just need these to see,” he yelled back as he raced forward again.

Neville: The conditions seemed to swallow us. The other boats in the bay were lost behind a wall of driving rain. VHF emergency distress signals screeched in alarm, and calls of “Mayday, mayday, mayday” were broadcast almost constantly. But our world and focus had been reduced to only what we could see and struggled to control.

I was numb with the certainty that Dream Time would be lost on the rocks. Ninety feet of chain was not enough in these conditions, not with such poor holding. The wind was tearing through our anchorage at a stinging 70 knots, and the rain was now so heavy, our decks were awash, driving Dream Time so low in the water, for a second I thought we were sinking. We later learned that a staggering 20 gallons of rain per square meter was released by the storm in one hour.

We turned on our sailing instruments and the tricolor and deck navigational lights. While working to secure the remains of the cockpit canvas—zips had parted under the strain, and I was concerned that the canvas, or worse, the fiberglass rod battens supporting it, could cause injury or tear free and get swept aft into the screaming wind generator—we both felt a heavy shock from the bow. Catherine, who went below while I threw down the last of the cockpit cushions, shouted that she could hear chain rattling from the forward locker.

Our snubber hook had bent and let go. The anchor was somehow holding. But now, as the series of colorful cable ties attached to the final few links warned, almost all our chain had been dragged from the locker. I had to secure our double storm snubber before we lost all our gear over the bow. The southwest wind screeching across open water had already built seas to 6 feet; I sensed we had only seconds before we lost all our ground tackle. After our first tsunami warning in the South Pacific, we had spliced a line to the last link and secured it to the backing plate of a deck cleat in the event we might one day have to quickly dump all our gear, cut the line and race to deep water. But how long exactly had I made the security line? Could the ¾-inch rope possibly hold under this load—or would it chafe through the hawse pipe? If chain and line tightened, would I even be able to reach one of the last links to secure our storm snubber or would it be too far over the bow?

While I was hunched over the bowsprit struggling to secure the snubber, the Beneteau punched through the rain just a boat length away. Wind was clawing and tugging at the mainsail and, from an unzipped stack pack, had flogged the sail up the mast to the first set of spreaders. The Beneteau’s wind generator, the same model as ours, had already lost two blades. I glimpsed people scrambling in the cockpit before the wind swept the boat from sight. It seemed hopeless. Thoughts of collision, which would normally entirely consume my attention, were forced aside. We had to focus only on the things we could control—actions that would increase our safety. Everything else was a useless distraction.

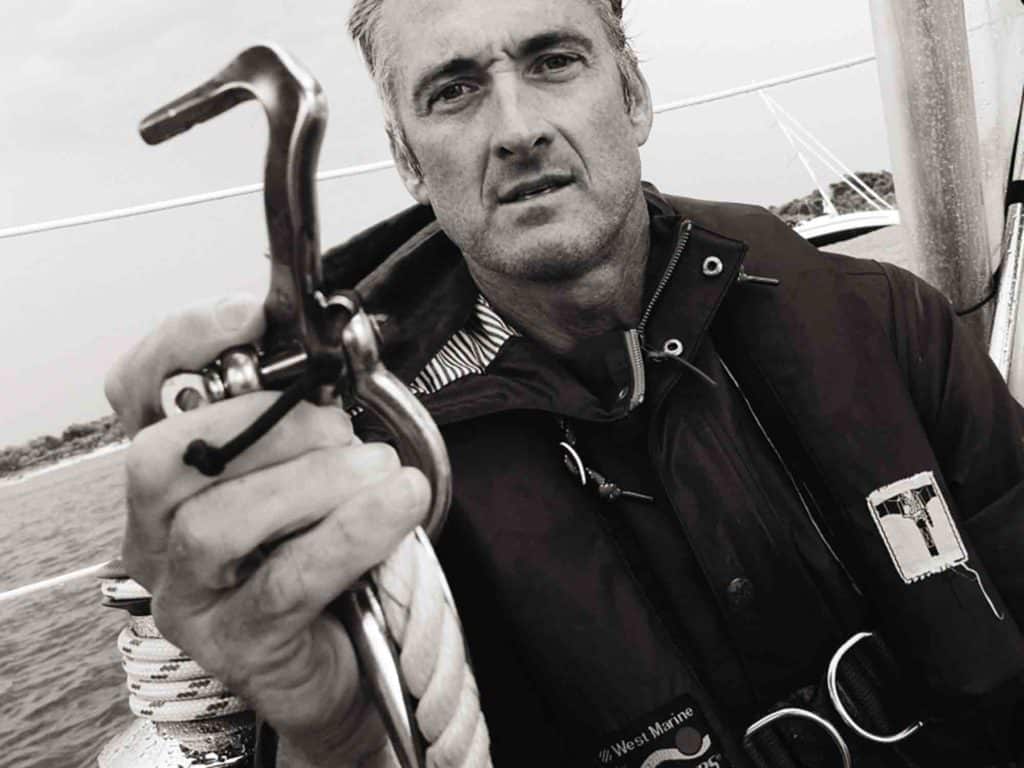

Dripping wet and shaking, from cold or adrenalin, I forced my attention back to the snubber but was finding it difficult to see. My sight was fogging. The dive mask was steaming my vision. I had to breathe only through my mouth, but leaning forward into the blast of wind and rain made that almost impossible. With the double snubber finally attached and the captive latch secured—a modification we had made in New Caledonia after heavy, pitching seas caused Dream Time’s bow to rise and drop so violently, the snubber hook let go—I released the windlass. The wind caught Dream Time, sweeping her hard downwind until the two 20-foot lines tightened, stretching under the intense load before dragging us sharply back to face the storm.

I had no idea where we were in the bay. Visibility was barely a boat length; the beach, the rocks and the town of Colònia Sant Jordi were all hidden in the storm. Staggering aft to the cockpit, I glimpsed the Beneteau close behind us, heeled hard over, her starboard rudder exposed. She was on the rocks.

With the double snubber attached, we had time to assess our position: The erratic and drunken track on the chart plotter told the story. Dream Time was 350 feet away from her original anchorage, and we were now a distressing two boat lengths away from the rocks. The depth gauge showed just 2 feet under our keel.

Catherine: We were much closer to land and could now see that the Beneteau had lost its terrible fight and was firmly up on the rocks and being pushed around by the crashing sea. Neville then turned to me, made eye contact and yelled over the screaming wind, “If we end up on the rocks, we stay on the boat, OK?” I agreed and said OK.

Then with everything done that could possibly be done, all we could do was hang on and try to hold the boat into the wind as long as we could and wait for the system to pass, all the time listening in silence to the seemingly endless frightened emergency calls and distress alarms broadcast on the VHF.

The weather did eventually move on, and anyone lucky enough to still be on their anchor, including us, began the process of figuring out what had been damaged, broken or lost—and those still afloat thanked their lucky stars.

About an hour after the worst weather had passed, a Civil Guard helicopter arrived and hovered over the grounded Beneteau, where it lowered a rescue worker and a basket before airlifting an injured person off the rocks. A catamaran swept ashore in our bay also called a mayday, requesting immediate evacuation. The distressed voice on the VHF said seas were driving their boat farther onto the rocks. They were taking on water and sinking. The Civil Guard responded professionally and calmly, gathering details and assessing the situation before asking directly, “Captain, are you and your crew in immediate danger?” After a long delay, a dejected reply came, “No, we are not in immediate danger.” With dozens of boats damaged and wrecked in the Balearic Islands, the Coast Guard had to prioritize its resources. The family on the catamaran would have to wait.

We believe diving on the anchor and understanding seabed conditions helped prevent us from dragging onto the rocks.

Later, a rescue vessel moved from boat to boat around the bay. When they got to us, the two people on the bow made eye contact, and as I raised my hand to wave, they made a thumbs up sign and waited for me to reply. Are you OK? Without saying anything, I returned the thumbs up. We’re OK. Then they moved on to the next boat. And at the end of the day, police divers started working around the four boats in our anchorage that had not been so lucky.

I like to think it was our little Dream Time that decided, in the strongest wind we have ever experienced, to throw off the snubber hook and pay out all of her chain because we were both frantically doing everything else we could think of, and because she knew, at that moment, that deploying all her chain was our best chance of getting through the storm in one piece. And she was right. Thank you, Dream Time.

After the Storm

Since the storm, we have measured the anchor-chain security line, which is long enough to pass 1 foot forward of the windlass, leaving enough room on deck to secure a chain hook or cut the line if required. Our old swimming goggles, that cover just the eyes, have now been relocated to a handy cockpit locker.

In preparation for our world voyage, Dream Time’s entire foredeck was rebuilt in Glen Cove, New York; the balsa core was removed and replaced with solid fiberglass. The windlass and forward deck cleats are all mounted in this reinforced area. Our windlass, a Lewmar V3, and our primary 60-pound CQR anchor are both rated for boats 10 feet longer than Dream Time. Our secondary 45-pound CQR was ready to deploy at the bow with 150 feet of 9 mm chain and a matching length of ¾-inch triple-strand nylon, but we did not have the sea room to deploy it.

When the wind shifted 180 degrees, our CQR did reset; we believe diving on the anchor and understanding seabed conditions helped prevent us from dragging onto the rocks. Also, we anchored in the center of the bay in anticipation of a potential wind shift, giving us enough room to swing and increase our scope if necessary. Additionally, storing the storm snubber in the forward deck locker by the windlass helped to reduce the time it took us to respond.

The working load of our Wichard chain hook is listed as 1,500 pounds; however, the conditions proved too great and twisted the hook almost 90 degrees before allowing the chain to fall free. Incidentally, we had replaced our single snubber line just a few weeks before the storm. It is interesting to note that the chain hook bent before this line broke.

Our windlass was fully tightened, but with no snubber to hold the heavy load, the strain simply overwhelmed the clutch and dragged 300 feet of chain over the bow. We still do not know how the last few feet of chain remained in the locker.

Neville and Catherine Hockley have recently completed their 13-year circumnavigation aboard Dream Time. Read more about their adventures at zeroxte.com.

Dream Time’s Storm Snubber

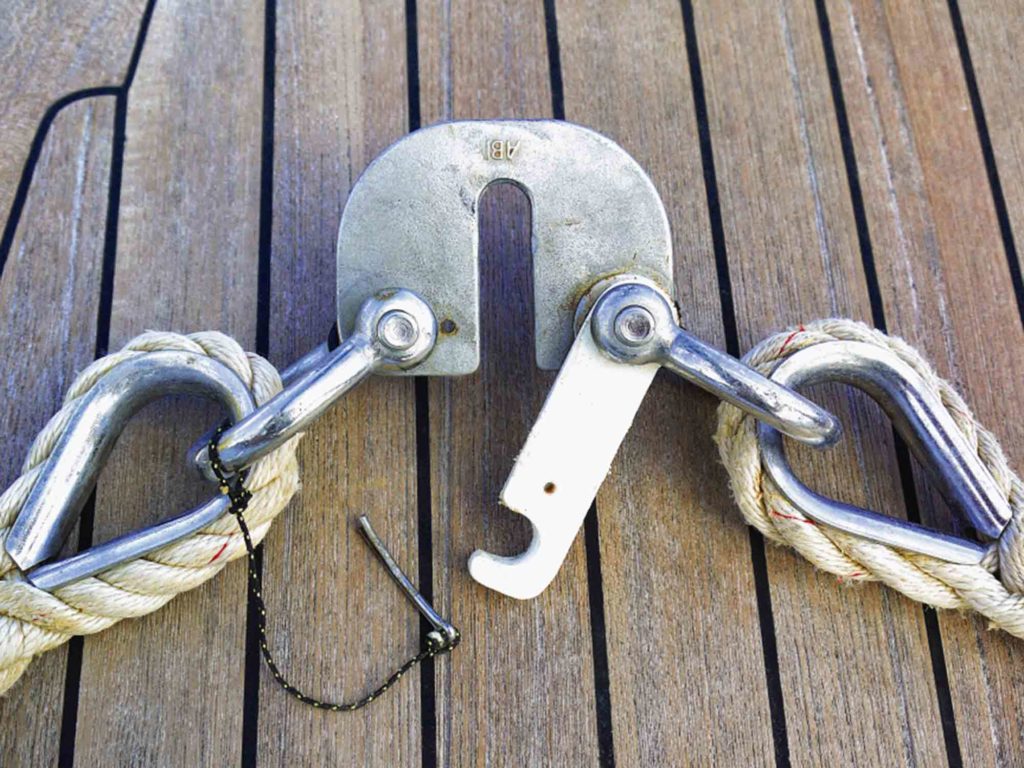

Dream Time’s storm snubber consists of an ABI chain grabber (see photo previous page) and two 30-foot 3/4-inch nylon lines each attached to the plate by a thimbled eye splice and shackle. To deploy, we secure one line to the starboard bow cleat, then pass the second line forward of the bowsprit and under the anchor chain before cleating off to the port cleat. Both lines have chafe guards in place, which when positioned at the fairleads, ensure the lines are of equal length and the grabber centered off the bow. With lines secured, the grabber is hooked to a chain link and additional scope paid out until the load shifts from chain to snubber lines. Important: To allow for line stretch, a minimum of 6 extra feet of chain should be released and allowed to hang aft of the grabber. Heavy seas and extreme pitching can result in the grabber falling free from the chain. To prevent this, we fabricated a simple captive latch, which also makes it easier to deploy.

The advantage of this storm snubber is that loads are shared between two lines and deck cleats. Additionally, should one line fail, the snubber will continue to perform under the second line. We have also found that the double storm snubber reduces sheering, the side-to-side swaying of the bow, and holds Dream Time more evenly to the wind.