Should I stay or should I go?

This punk-rock anthem to indecision seems written especially for cruisers. As each season winds down, one query tops the usual weather-and-repairs yammer in every port: “So, where you guys headed next?”

When my wife, Rebecca, and I sailed from the Pacific Northwest in 2009, that answer was south, at least to start. Each winter we pushed farther on Liberte, our Beneteau 361, lured by monkeys, waterfalls and that age-old temptation of new horizons. Liberte dawdled through Costa Rica and Panama, through the Panama Canal, and on to Guatemala’s Rio Dulce, Belize, Florida, Cuba and the Bahamas. And boy, are we glad we did.

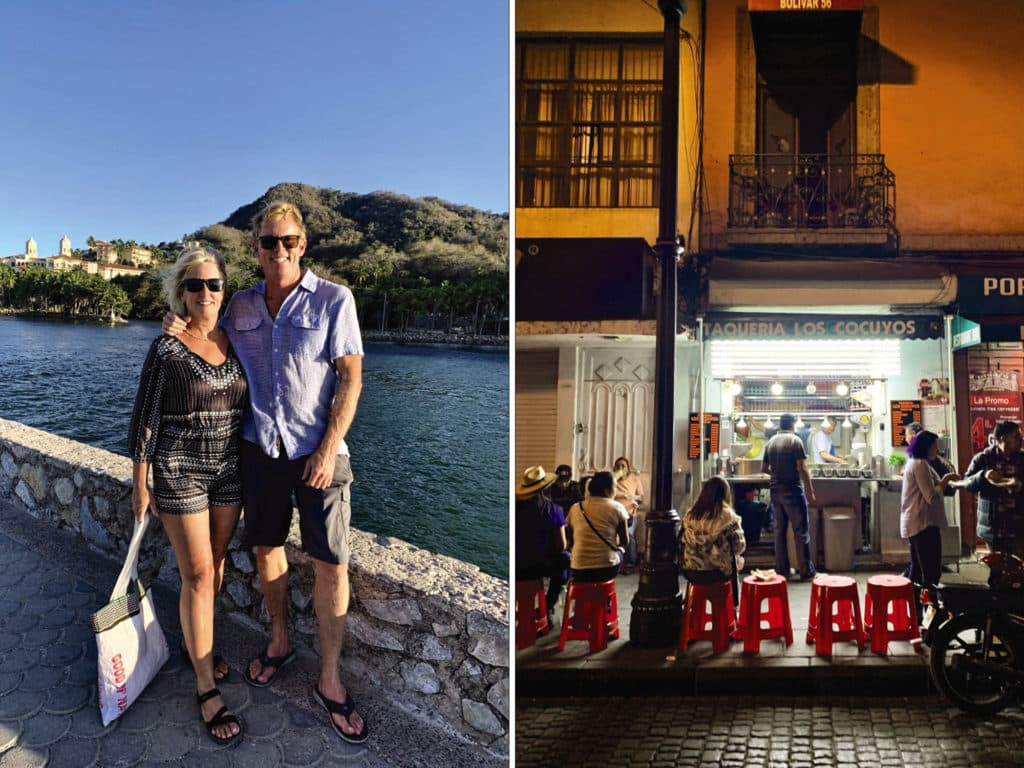

But by our third season in the Bahamas, when that destination question arose at a farewell dock party in Green Turtle Cay, Rebecca and I knew our answer. We wanted to sail with humpback whales, anchor under mountains, enjoy endless blue skies and temperatures in the 80s, and yes, eat tacos and salsa on street corners. We missed the weather, people, food, cost of living, landscapes and sea life of Pacific Mexico. We wanted to go west.

And how tantalizingly close it was. Just 36 hours by car from Fort Lauderdale to Puerto Vallarta, or a mere three hours and 46 minutes in an airplane. But certainly not by boat. So, what was the best way back? My impetuous side wanted to cast off the lines and see how far we’d get. That approach had worked before and likely would again. But over the seasons and miles, I had learned to eliminate all the variables that I could. And I knew firsthand that the return route had variables aplenty.

Coming to the East Coast, Rebecca and I (and friends as crew) had mostly enjoyed solving each aspect of our voyage with a can-do attitude. We’d run the gauntlet of Tehuantepec and Papagayos winds, dodged (and once hit) unlit pangas in the dark, threaded miles of fishing longlines, and piloted Liberte through a Salvadoran surf break to shelter. What was then novel and exciting now seemed like one obstacle after another.

We could also hire someone else to take Liberte around on her own hull. The cost would include delivery crew and provisions, fuel and Panama Canal transit fees, engine hours and boat wear and tear, along with extra dollar signs if Liberte was struck by the frequent lightning in Panama or nailed one of the giant logs that flood down those Central American rivers when it rains. It was back to the same unknowns with someone else making midnight make-or-break decisions.

What about shipping overland? Truckers informed me in a variety of regional dialects what I was up against. For most, our humble boat haul sounded as though it was more trouble than it was worth.

“You say you’re 12½ beam?” (I could literally hear head scratching.) “Yeah, I’ve gotta get an extra escort, and that’s more bucks per mile. Call my buddy, maybe he can help you.”

What if I sailed the boat to Galveston, just 1,345 land miles from San Carlos, Mexico?

“It won’t make much difference; I’ll charge about the same. Mexico you said? I don’t deliver into Mexico. Best I can do is drop you off in Tucson at Marco’s crane, and they put you onto another truck going south.”

How much was that truck going south? How much did Marco want for his crane? The more I tried to engineer a solid route with a budget, the more uncertainties arose. I could truck from Cancun to Puerto Vallarta, but throw in insurance, as well as decommissioning and commissioning, and we were back to square one. My most desperate hours were spent chasing some ghost who, rumor had it, wrangled boats over the mountains of Guatemala. By this point, I wasn’t sure I wanted Liberte going anywhere at 65 mph, scooching under trees and bridges, bouncing over train tracks, vibrating things loose on her merry way. The savvy sailors who reported good outcomes by land spent days of prep unstepping the mast, and wrapping, securing, and otherwise protecting their pride and joy. I admired their work…and I wanted to avoid most of it.

So, for simple math, less labor and a straightforward outcome, we bet our money on shipping Liberte back west by sea.

Though research dredged up horror stories of boats held for ransom or dropped in the wrong port, I was pleased with Sevenstar Yacht Transport’s reputation and happy they were going our way. Since the Florida to West Coast routes are busiest after the Miami International Boat Show in February, our haul would likely happen in late February or early March. The next trick was entwining our tiny boat with this juggernaut of international shipping. From its Amsterdam headquarters, Sevenstar directs a fleet of 120 transport boats, shipping 1,500 yachts a year up to 60 meters and 650 tons.

“We must be the smallest thing on your ship,” I told our agent, Lauren.

“We handle boats of all sizes,” she answered, quite diplomatically.

The agreed-on price for little Liberte was $15,000 from Palm Beach to La Paz, Mexico, which by my uncertain math was not far off the other options and may have had them beat. This we wired in advance to Deutsche Bank AG, a small fortune gone forever from the cruising kitty.

RELATED: Sailing to Mexico with the Baja Ha-Ha

Shipping by boat, the mast could stay in place, a real selling point. Our contract included loading, lashing, discharging and transport insurance, as well as a cradle to hold Liberte. (Three months later, the Baltic 130 My Song fell overboard in transit, blamed by shipper Peters & May on a bad cradle supplied by the yacht owner.)

When I asked Lauren for her advice on our travel plans (we had roughly three weeks to spend while our boat moved without us), she emphasized flexibility. One contract line in particular caught my eye: “Demurrage, Euro $15,000 per day.” It was an understandable yet terrifying penalty for failure to load or discharge on time, and I realized we didn’t want to miss either date with the Dutch ship.

Rebecca worked out travel solutions. As soon as Liberte was loaded, we would book the next flight to easy-to-reach Mexico City to enjoy culture and food, knowing that daily AeroMexico flights went to La Paz. Lodging was made flexible along the way.

You can bet Liberte arrived plenty early in Palm Beach. After a delightful romp of a sail up from the Keys, we came through the tidal waves of Lake Worth Inlet in the dark and anchored in West Palm. It’s not an entirely straightforward anchorage, but one that did the job, especially with reciprocal privileges at the Palm Beach Sailing Club a short dinghy ride west. All day we watched the nicest yachts in the world slide by, headed for Rybovich SuperYacht Marina. We knew our own mothership would be the 465-foot M/V Marsgracht, bound from Europe, and it was exciting to see her AIS signal steaming our way across the Atlantic at a steady 14 knots or so.

Timing is tricky in this business. Email updates qualified our shipping dates with “AGW WP,” shorthand for “All going well, weather permitting,” and added this disclaimer mariners can appreciate: “Estimated arrival times are taken in consideration of weather for the period of the year and port operations on route.” No kidding! It’s amazing shippers could make these myriad gears mesh at all.

To prep Liberte for ocean transport, we stripped her bare, as we do each season for summer layup. Rebecca and I flaked and stowed sails, and removed wind-generator blades, Bimini and dodger. We even wrestled the deflated RIB belowdecks, a disappearing act that amazes us each time.

The morning of our loading on February 24, we came about as close to a fight as we have in all our miles at sea. This amid a slapstick scene of trying to lash tarps on deck in a gusting breeze, since I seemed oddly and suddenly paranoid of finding Liberte covered in black soot from the ship’s engines. Separation anxiety, one surmises.

And then it was our turn. Since Marsgracht is the kind of thing we spend night watches avoiding, it was surreal to come alongside a piece of steel this big. We appreciated the settled sea state and still wished we had bigger fenders. The shipboard crane moved overhead. There were divers in the water and a loadmaster above. Men swarmed our deck with an air of easy competence. I knew we were in good hands when they belted out disco songs and debated who had the best-looking socks (as they respectfully pulled off their shoes). While I disconnected twin backstays to make way for the lift cradle above, the Kiwi loadmaster eyeballed our patchwork of tarps and shook his head.

“I’d get those off if I were you,” he said. “They’ll just go in the first blow anyway.”

So Rebecca and I hopped to it, ripping away hours of work in a couple of minutes and giggling to ourselves. Then we grabbed our backpacks and boarded the pilot boat; Liberte was now someone else’s job.

The crane groaned, straps tightened, and up she went. It was incredible to see the size difference between the two boats as Liberte flew higher than she’d ever been in her life. We climbed on Marsgracht to reattach backstays and close up our boat. Sparks flew as Ukrainian welders secured the steel cradle. I found myself testing the straps holding Liberte to the deck. Nope, skipper, time to step away. Just pat your boat on the backside for luck and remember to give the hatchboard key to the crew in case customs wants to see inside.

The rest of the day I had that incomparable finish-line feeling I so love from boat-delivery and ocean-racing days gone by. I was wind-blasted and satisfied, the buzz of accomplishment balanced nicely against weariness in muscle and mind. While we sipped a celebratory drink with friends and then jetted away, Liberte went back out to sea. And as we prowled the trendy Condesa neighborhood of Mexico City, Liberte steamed on night and day, around Cuba and south at speeds she’d seen only briefly when surfing big waves in following current.

By the time she made the Panama Canal, we were swinging in a hammock above the lovely lake at Valle de Bravo without a care in the world. I was so relaxed that I snoozed through her rapid canal transit, in contrast with the weeks of work and waiting it had taken us going the other way.

And only a boat owner can know the irrational joy of reunion. It was March 14 in La Paz, exactly as promised, and there she was, 17 days and 4,000-odd miles on, waiting patiently beside her mighty friend.

The Yanmar fired up, and we motored to nearby Marina Costa Baja. Despite my worry, there was not a speck of soot in sight. (It helped that Liberte rode in the front of the ship, forward of the stacks.) Only one thing was amiss: A prong of aluminum toe-rail chock had broken off. I put it in my pocket.

“If that’s the only damage, I’ll gladly keep it as a souvenir,” I said.

Twenty-four hours after we took possession, our boat was rigged and ready, a Mexican courtesy flag hoisted into the perfectly blue Pacific sky. A local agent recommended by Sevenstar handled our clearance, made simpler by the fact we still had our 10-year Temporary Importation Permit from clearing into Ensenada in November 2009. Thanks to our agent, we had time to enjoy the swimming pool, and in the evening walked the malecón and nibbled street corn with cotija cheese, mayo and chili. It was a fine reentry.

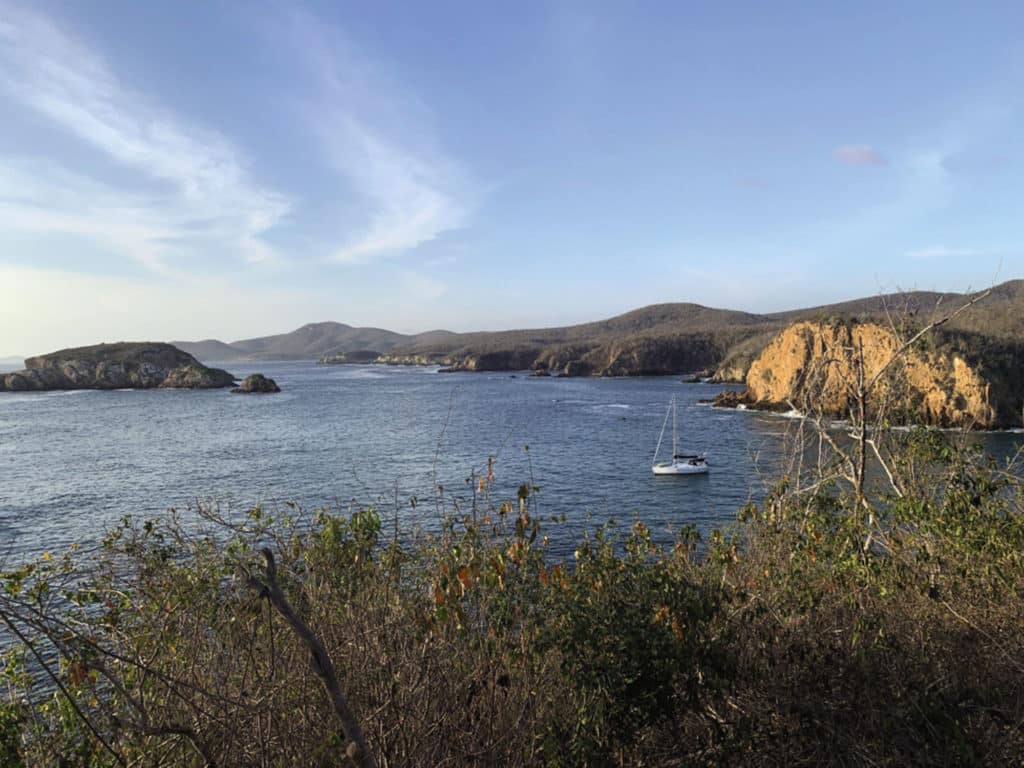

On our crossing to mainland Mexico, our old friends the humpback whales swam past to say hello. South of Cabo Corrientes, Rebecca landed a hard-fighting Pacific jack, and we gratefully ate sea-to-cockpit-table that night under another explosive sunset.

It came down to a rapturous realization when we dropped anchor off a fishing village, watched the light fade on the mountains and heard the pure, high notes of a mariachi trumpet from shore.

It was good to be home again.

David Kilmer spends his summers running the 60-foot daysailer Sizzler in Coeur d’Alene, Idaho, and his winters cruising warmer waters.

Tips To Ship

- Find a company with a good reputation that specializes in the route you want. Be flexible on origin and destination if you can.

- Get a contract sorted well before shipping, with exact measurements of your boat’s LOA, beam, height overall (bottom of keel to top of mast) and all-up weight (not tonnage). Ensure that customs papers are in order for origin and destination. Ask the shipping company for reputable local agents.

- Empty tanks, but leave enough diesel for loading and unloading. Remove sails, canvas and other items on deck. Cover Dorades and hatch openings, and secure all hatches. Wax the stainless. Some owners shrink-wrap their boats. Make sure you have big fenders on all sides of your boat and long lines handy.