There were times, in the immensity of the Indian Ocean, when David Pollitt would look out from his boat and see around him a great symphony.

Alone again before a powerful force, he swayed between risk and control in that space, known to circumnavigators and conductors, that lies between catastrophe and rapture.

“It’s a moment you work so long to get to,” said Pollitt. “You have a hugely powerful instrument in front of you. You are amid 2,500 people, or in the middle of an ocean, on a small platform. There’s adrenaline, motion. You are in danger the whole time. You cannot make a mistake, you must get it right, to bring the composers, these great men, right to your side, to take you to places that are so difficult to describe.”

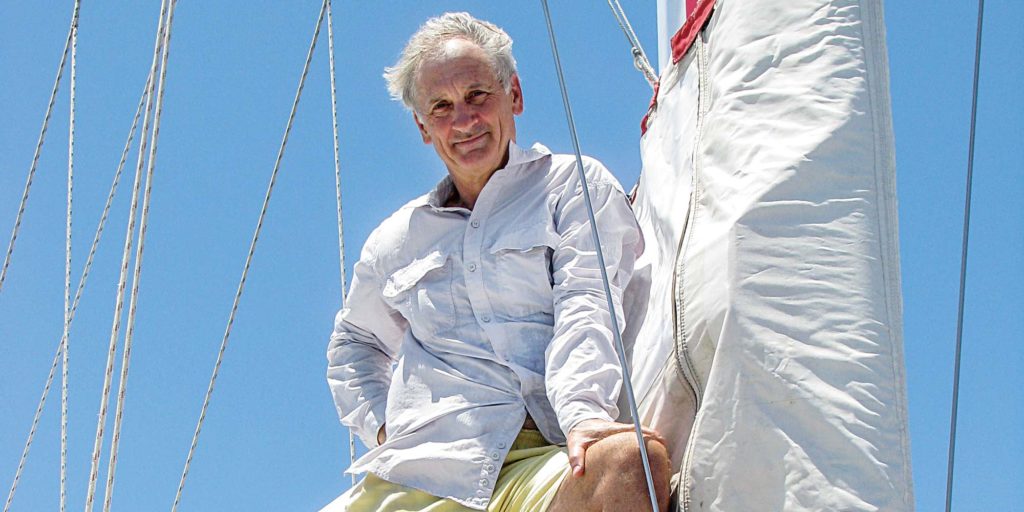

It was a quest for such rare transport that led Pollitt off the international music circuit to Shearwater, a 47-foot catamaran, and a three-year solo round-the-world sail. He was 57 years old when he began in June 2009.

I happened upon Pollitt in June 2012 in a West Palm Beach, Florida, marina just after his homecoming. I snapped a few pictures, and later caught up with him in a Skype interview from Colombia, where Pollitt had sought refuge.

Pollitt had always lived in high profile. His Hungarian grandfather, Albert Szent-Gyorgyi, won the 1937 Noble Prize in physiology for his discovery and distillation of vitamin C. Later, as an American citizen living at Woods Hole, Massachusetts, he helped unravel how muscles contract.

Summering at his grandfather’s Cape Cod home, Pollitt learned to sail on dinghies. “If you learn on a Sailfish in very rough weather, you develop an instinct for sailing, and very good reactions,” he said.

Though he earned his captain’s license at the Chapman School of Seamanship, Pollitt took up the violin at the Juilliard School, and later, after a motorcycle accident, the baton. Adopting Szent-Gyorgyi for a middle name, he guest-conducted orchestras in Turkey, Italy, Uruguay, Hungary, China and other countries, and became a music director at symphony orchestras in Arlington, Virginia; Tallahassee, Florida; and Greenville, South Carolina.

The nine-year Greenville gig ended in 1999 on a sour note as he pressed efforts to open the symphony experience to African-American children and fought with the board over finances. Mulling his future, a childhood fantasy came in focus.

“It’s very hard to come up with anything that can absorb, or captivate, one as completely as music and conducting. I’d been on the ocean, and was fascinated and challenged by the emotion. It was one of thefew things that I thought could maybe fill that huge space that, given one little life and the small time we have, matches the magnificence and hugeness of the places that music took me.”

Being on a boat in an ocean, he found, was like standing in front of a symphony orchestra. “You are geared up. Many people are counting on you to get it right. I felt on the podium that I was in danger the whole time, getting a whole lot of nuts and bolts right, while at the same time transporting the musicians and audience to an inspired place.”

Pollitt’s circumnavigation is captured beautifully on his site wingmast.com, which shows his route dotted with photos and video. His blog sailblogs.com/member/mangoandme, named after a dog he had to send home, contains a detailed diary.

Among the highlights that caught my eye: his efforts to keep the big wing-masted cat reined in; his top speed was 22 knots under a third reef in the middle of the Pacific; he could make 250 miles a day, and burned less than 500 gallons of diesel in three years.

There was the terror of land — approaching both the Great Barrier Reef of Australia, and the southwest coast of Africa. He carried no life raft. Though equipped with an EPIRB, a satellite phone, new electronics and backup autopilots, he felt mentally safer with his boat’s flotation than the false assurance of abandoning ship to a raft. Because of his years on that Sailfish on Cape Cod in very big seas, “it was never a fear of mine to end in the water.”

He took no music. “I never listened to music. It knocks off your senses,” he told me. “The first warning sound is my sense of hearing. Suddenly, the wind sounds different. Sure enough, you’ve changed course.”

And, it wasn’t fun. “It was too great and too dangerous to have fun. The great pleasure was in the challenge, and facing this very animist ocean. It is waiting to swallow you.”

Pollitt rounded Africa with dread. “Before leaving Cape Town, every conversation is about what are you going to do now. I was scared to touch land again. I appreciated what must have happened to [Bernard] Moitessier,” the yachtsman who gave up winning a circumnavigation prize to go around again. (Pollitt also posted on his website Fatty Goodlander’s CW column on the circumnavigator’s post-trip depression, April 2005).

Sure enough, when he touched Florida, he felt pressured. “I’d spent everything I had ($500,000). I had no nest egg, no security. There was no going back to music. As much as I miss it, the United States is a very, very competitive country. Every job in a U.S. orchestra gets 600 applications. It takes years to pay your dues. When you exit, the little void you left is immediately filled by 600 people who want your job. If you leave at 50 or 55, you are now considered very old.”

He sold Shearwater and moved to Colombia, which he’d visited on his cruise. He found the people “warm and friendly. You don’t feel the government breathing down your back. The women are beautiful, and there is no bias. I’m learning Spanish. I’ve been alone all my life, and I don’t like it. I guess I’m much more afraid of dying in a hospital bed alone than dying out on the ocean.”

He built a big modern house on a piece of land outside Armenia, a town in western Colombia, and tried to settle down. He told himself it was the end of the road. But periodically, he’d hear the echo of a conversation with a crusty Cape Towner.

“Will you continue sailing?” the old mariner had asked.

“No. I’ve done it.”

“In five years you’ll be singing a completely different tune.”

The old man was prescient. At age 66, with no partner in view, and fading memories of the terror he felt on Shearwater juxtaposed against a recent violent house robbery in which he nearly lost his hands, Pollitt is thinking again of the sea. I spoke with him in November.

“The beauty of it all has captured me again. I’m asking myself, When I’m on my death bed, do I say I spent my last years alone in a house, as beautiful as it is, or going around Cape Horn and around the world again? The answer is very clear.”

Jim Carrier is a CW contributing editor.