There are two situations that accelerate vessel maintenance: one, using your sailboat too much, and two, using it too seldom. For the past six decades of living aboard, I’ve erred on the too-active side of this equation. During the past 20 years of our cruising lives, my wife, Carolyn, and I have averaged between 5,000 and 8,000 ocean miles annually. That’s a lot of wear and tear on our sails, chafe on our running rigging, and hours on our Perkins diesel. Now, totally unexpectedly, we find ourselves staying put, tethered to a mooring at the Changi Sailing Club in Singapore due to the new normal of COVID-19 international-travel restrictions.

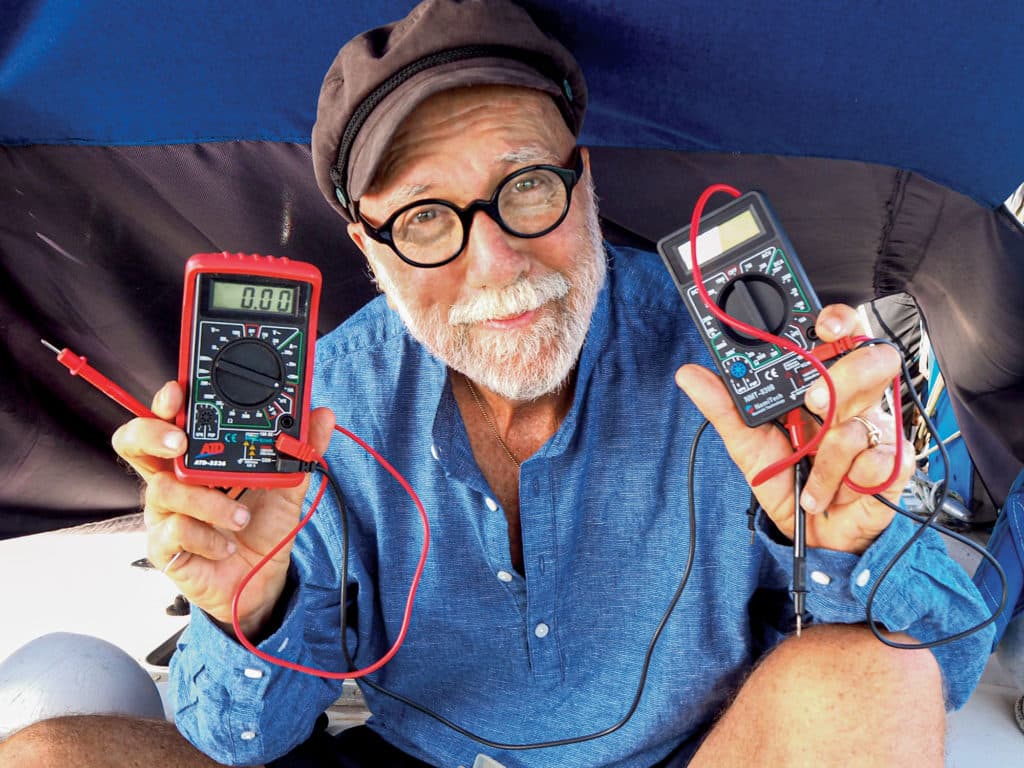

The result is, simply put, electrical issues. That’s right—I used to wear a rigging knife, but now I’m thinking of getting a holster for my ohm meter. I’m surrounded by bad electrical connections.

Part of the problem is that Ganesh, our 43-foot French-built ketch, grows ever more complicated electrically, with burglar and bilge alarms, automatic anchor lights, and 5-volt USB charging outlets springing up from the bilge like weeds. Yes, I attempt to keep our vessel simple. Despite this, we now carry 12 computer hard drives and three DSLR cameras, each of which is stowed in a humidity-controlled environment. Worse, we have more Apple products than a floating orchard. But our laptops, tablets and mobile communication equipment, along with our cameras and digital-storage devices, allow us to be digital waterborne sailing nomads, as Carolyn likes to say. Not only are we able, but we’re required, to keep in touch in order to earn our living daily in the far corners of our planet.

I used to wear a rigging knife, but now I’m thinking of getting a holster for my ohm meter.

Another contributing factor electrical-wise is our abhorrence of marinas. We just don’t like the trailer-park lifestyle, even afloat. Plus, the meanest trailer park in America doesn’t pack its residents toe-rail-to-toe-rail as tightly as a posh marina in Monte Carlo. Thus, we’re always on our own hook or hanging on a mooring ball, which has the additional benefit of being able to pivot into the wind, eliminating the need for electrical air conditioning. (Thank God for wind scoops!)

Needless to say, we have to share our natural resources. Currently, in Singapore, we are joined in our Changi anchorage—actually, it’s just a bulge in a constricted commercial waterway—by moored yachts, passing fishing boats, cargo ships, ferries, entire fleets of government craft, cruise ships, and international warships from numerous nations. My point? We regularly get wakes—big ‘uns. Often they slop on deck, and more than once we’ve had salt spray bound aboard through our fore, midship or aft deck hatches. We regularly roll from rail to rail. This is the price we pay for living almost for free in the most expensive, most sophisticated city nation on our planet.

Here, there’s a long fetch to both the west and northeast, and a strong tidal current is a factor as well. And while the winds are generally light, the nor’easterlies during winter are brisk and the summer squalls severe. And we’re often tide-bound and sitting sideways to the seas in a heavy haze of tropical salt spray.

I’ve used a variety of ways to keep power flowing: marine-grade crimp connectors, soldering and, occasionally, twisting and taping.

Actually, as challenging as this sounds, we love this place. It’s like living in a three-ring aquatic circus. Something exciting is happening every second, day and night, just outside our portholes. However, as much as we’re enjoying our salt-laden environment, our electronic doodads aren’t. The aforementioned haze of tiny specks of sea salt eventually settle on every surface of Ganesh. Worse, salt is hydroscopic, and the warmer the temperature, the greater the effect. Not only do these drifting salt molecules attract water to all our wires and electrical connections, but they also bathe and boil them in a mild acid solution as well.

The unfortunate result is, as my wife Carolyn jokes, “Christmas year-round.” Our cabin lights blink on and off—and then don’t function at all.

Luckily, I’m a regular Sherlock Holmes of bad electrical connections. I can sniff them out either by testing for voltage or checking for continuity. The trick is to remember that electrons don’t just have to arrive at our 12-volt devices, but they also have to return to the other post of the battery to complete the circuit. To put it another way, it’s not just the two wires that deliver power to, say, our depth sounder that must be in solid contact with our main battery bank; it is the entire circuit that must be making contact. Think battery terminal, monitor shunt, main battery switch, terminal block, panel switch, fuse or circuit breakers on the positive side, plus any surprises on the negative ground side as well. (Note: This is a best-case simple example; many branching and re-branching circuits on Ganesh are far more confusing!)

Of course, a circuit, like an anchor chain, is only as good as its weakest link. Let’s consider our nine mismatched solar cells. Obviously, they’re outside. That means they’re not only misted with salt continually, but they’re occasionally struck by exploding seas as well. And they come from the factory with short wires but are mounted a long way from our batteries. This means that they have to be connected to each other and the vessel’s electrical system in such a manner that they (hopefully) function for long spans of time.

And whose job is this? Well, at our income level, it’s mine, and over the years, I’ve used a variety of ways to keep power flowing: marine-grade crimp connectors, soldering and, occasionally, twisting and taping. The latter is crude but cheap, and works—for a brief while. But the problem isn’t connecting the wires; it is keeping them connected or, to put it another way, to prevent the intrusion of those dreaded salt crystals that lead to corrosion.

Crimping on a quality connector is a good first step, for instance, but sealing it is the real challenge. Don’t forget: When two pairs of wires are joined, not only is a firm connection necessary, but each crimp needs to be moisture-proof, and negatives and positives must, of course, be kept separated.

Think about this real-life challenge: When I bought her, all of Ganesh’s mast wires had been cut to remove the main and mizzen spars. I could have spent the time and money to fix this correctly, but I sailed around the world instead. Am I sorry I did this? Not really. I have only a few dollars and a limited amount of time. I don’t want to squander too much working on a boat that I could be sailing.

But back to my wiring example. Mast wires are located in a very active and very damp part of the boat. The masts vibrate, the deck flexes, the sun beats down, the rain pours. Yikes! So here’s the bottom line: Crimping on a connector and saying “good enough” doesn’t cut it if you want the electrical connection to still be conducting when you return to safe harbor.

Personally, I live in a practical world with only a handful of pennies, so throwing money at the problem isn’t practical. My solution is to use a redundancy of techniques. So, back to the mast wires again. If I’m using a crimp connector, I use liquid tape to seal each wire into the connector once crimped. Then I add a heat-shrink tube over the top of that, and another, longer heat-shrink tube to cover the first. Thus, I have three physical barriers against moisture absorption. Enough? Probably. But on certain critical wires, I don’t stop there. I coat the heat-shrinks with silicone seal, wrap the whole gooey mess with plastic wrap, and then tape it.

Crazy? Yeah. But effective. I’ve had exterior connections such as this last more than a circumnavigation.

Why not solder? I often do. However, soldering on deck in a breeze isn’t easy. Temperature is critical. If a connection is not hot enough, the contact isn’t good; too much heat, and the insulation melts. Of course, I attempt to use quality marine components such as tinned, double-insulated marine-grade 12-gauge stranded wire. But I’d be lying if I told you that I’m as careful wiring a cabin fan as I am our GPS, bilge pump or starter motor.

While in cruising mode, I find it relatively easy to keep everything humming electrically. I just slowly fix, fix, fix until it is all good, then immediately deal with anything that ceases to function. However, if I’m not in cruising mode, things gradually deteriorate without me realizing it.

The way I deal with this is by having a weekly, monthly and quarterly maintenance routine, in addition to our normal haulout-work checklist. Every week as I wind my eight-day ship’s clock, I also run the engine and bilge pump, and physically look into the bilge. Before I crank the engine, I check all its fluids, and feel under the transmission and pan for any early signs of leakage.

The moment the engine starts, I check to see if it is pumping raw water, and then I stare at its flow for a while. Does it appear to be pumping the same amount as last time? Is the exhaust gas invisible? If not, white smoke has a different meaning than black. I allow the engine to get up to temperature, then shift it into forward and reverse under mild temporary load to lube the transmission and keep the rear seal moist.

Next, I exercise my electronics by turning them all on and, for example, keying the mic of our SSB, etc. This not only keeps the copper surfaces of the switches clean, but the heat from each device dries out the electronics as well.

On a monthly basis, I spin the anchor windlass and steering wheel, and momentarily engage the autopilot. Ditto our burglar alarm (which is useless in zero-crime Singapore). On a quarterly basis, I check the lower-unit lubrication on our tender’s outboard and basically spin or move everything on the boat, specifically all 12 winches and Monitor self-steering gear. I move and rotate the sheave of every block on board, paying particular attention to aluminum masthead and boom sheaves that can freeze up in the blink of an eye. I also confirm that my bilge float switches are working and check my life rafts for water intrusion.

There’s a great irony here: After a lifetime offshore, not sailing my boat is the only thing I’m uncomfortable with. But we cruising sailors must embrace change. In a sense, that’s what our lifestyle is all about. An avid sailor by the name of Charles Darwin agrees. To paraphrase his writing: “Adaptation is more important than intelligence.” On a warming planet, while anchored directly below the equatorial sun, this is a life lesson I cannot afford to forget.

Cap’n Fatty Goodlander’s most recent project is to figure out how to remove the bilge pump from the sump under his engine, which he installed when the diesel was out.