Ted Turner was lit, again, in more ways than one, and he was letting people have it. Oh, boy. There was a time and place for everything, and for heaven’s sakes, not to mention simple common decency, this was neither one. Cocktail in hand, Turner was holding court in a noisy hotel pub in Plymouth, England, on the fateful 15th day of August in 1979, and he certainly had cause for celebration. But he was also, certainly, pushing all the boundaries.

Off to the side, nursing her own drink and with plenty to occupy her already worried mind, Doris Colgate—to whom Turner, the well-known media mogul who was also a champion, world-class sailor, was clearly addressing his comments—could only shake her head. She’d seen this movie before.

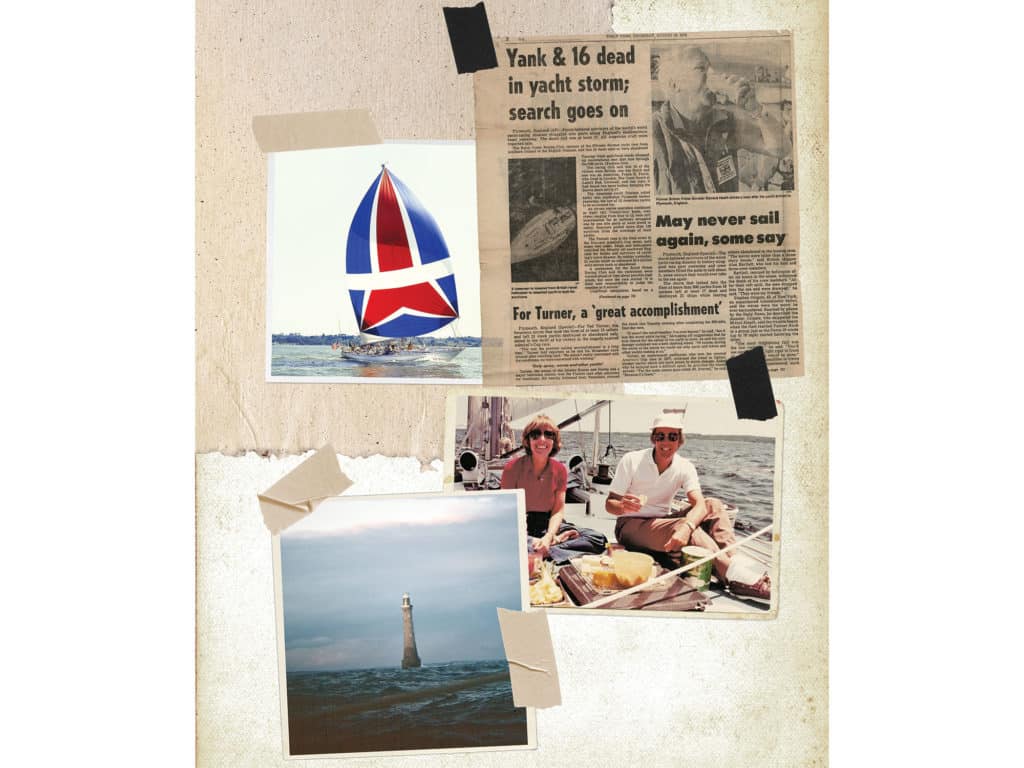

Late the previous evening, Turner had crossed the finish line off Plymouth aboard his 61-foot yacht, Tenacious, the provisional winner on handicap time of what would come to be known as the deadliest, most destructive yacht race of all time, the ‘79 Fastnet; the race was so named for the prominent rock off the coast of Ireland that was the primary feature of the racecourse, which all the boats had to round before returning to the English Channel and the finish line. Four days earlier, a massive fleet of 303 yachts had set forth from Cowes to begin the biennial 605-nautical-mile contest, which descended into utter and complete chaos on the third day when a powerful gale—with 70-knot gusts and 40-foot seas, well beyond the sporty but manageable conditions that had been forecast—ripped across the Irish Sea.

Among the yachts getting creamed in the maelstrom was a 54-foot US-flagged vessel named Sleuth, skippered by a vastly experienced New York sailor and sailing instructor—one who’d raced across the Atlantic on multiple occasions, not to mention competing in the Olympics and for the America’s Cup, among countless other races and regattas—named Stephen Colgate.

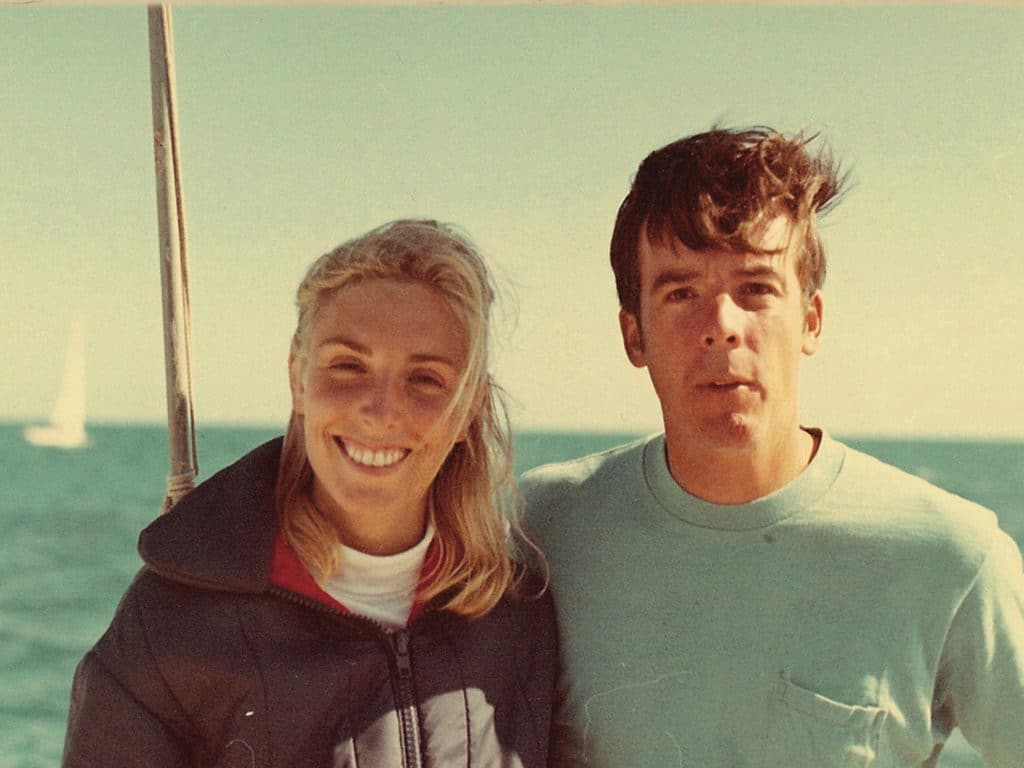

He was also Doris’ husband, Steve, with whom, a little over a decade earlier, she’d fallen head over heels in love at her very first sight.

The 1979 Fastnet would become legendary…for all the wrong reasons. It would spawn several documentaries; numerous postmortem investigations delving into the seaworthiness and structural integrity of the competing vessels; and a small library of sailing books, including John Rousmaniere’s definitive report, Fastnet Force 10 (the name refers to the prodigious number on the Beaufort scale, an empirical measurement that relates windspeed to observed conditions at sea; one never wants to be boating—or for that matter, anywhere but solid terra firma—in Force 10 conditions).

Turner had set foot on sweet, dry land the night before, where he was met by a waiting press corps thirsty for a first-person, firsthand update from a scene that was quickly becoming tragic. Rumors were swirling—unsubstantiated ones. It was clear that many boats had been dismasted or toppled, and that a huge, unprecedented rescue effort was underway (it would ultimately become the largest peace-time rescue operation ever, spanning 8,000 square miles and 4,000 people, in navy vessels, lifeboats, commercial craft and helicopters). But how many boats had come to grief? Furthermore, it was also being reported that there were fatalities, perhaps plenty of them. Had five sailors perished? Ten? Twenty? Nobody had a clue. The only sure thing known at the time was that the storm was still raging. And sailors were still dying.

Into all this uncertainty stepped Turner, with the opportunity to provide both insight and empathy. He chose not to. Instead, when asked by a British reporter about the brutal conditions, he wisecracked, “If it weren’t for these waves and weather (off the south coast of England), you’d all be speaking Spanish right now.” (The implication was that the powerful Spanish Armada in the 1500s would’ve crossed the English Channel and conquered the British Isles centuries earlier had it not been deterred by a savage storm. Turner never graduated from his alma mater, Brown University—though he did captain the sailing team—but he apparently attended some history classes.) And the only “bitter disappointment” he expressed in those first moments ashore was the remote possibility that some other, smaller boat might squeak ahead of Tenacious on corrected time and deny him victory. Winning. Turner made it abundantly clear it was his only concern.

As for the dead and missing? Crickets. As in, silence.

He doubled down when he saw Doris, who happened to be accompanied by Steve’s mother, Nina, on a road trip along the southern shores of England that had taken a decided turn for the worse. (Even in the best of circumstances, which these obviously weren’t, it would’ve been a strange journey; Steve’s relationship with his mom was, well, “complicated.”) Apart from his own, Turner wasn’t interested in anybody’s feelings.

This became clear when he spied Doris sitting alongside Pat Nye, the wife of another Fastnet skipper sailing under the Stars & Stripes, Dick Nye aboard Carina (Steve had also logged plenty of miles aboard Carina back on his home waters of Long Island Sound and also in the prestigious, international Admiral’s Cup series, and knew the extremely well-sailed and seaworthy boat well). Turner acknowledged the two anxious wives and basically said, loudly, that it was extremely unlikely anybody would see Sleuth or Carina—or their husbands—ever again.

Yikes.

This whole Fastnet race was an anomaly in the Colgate’s marriage; it had become very rare indeed for the couple to be separated, even briefly. Actually, Doris had sailed plenty of hard miles and races on Sleuth, and the sole reason she wasn’t alongside Steve at this very moment was because she’d made the decision to have her mother-in-law join her in England for the festivities, and to drive her from Cowes to Plymouth for the start and finish, respectively.

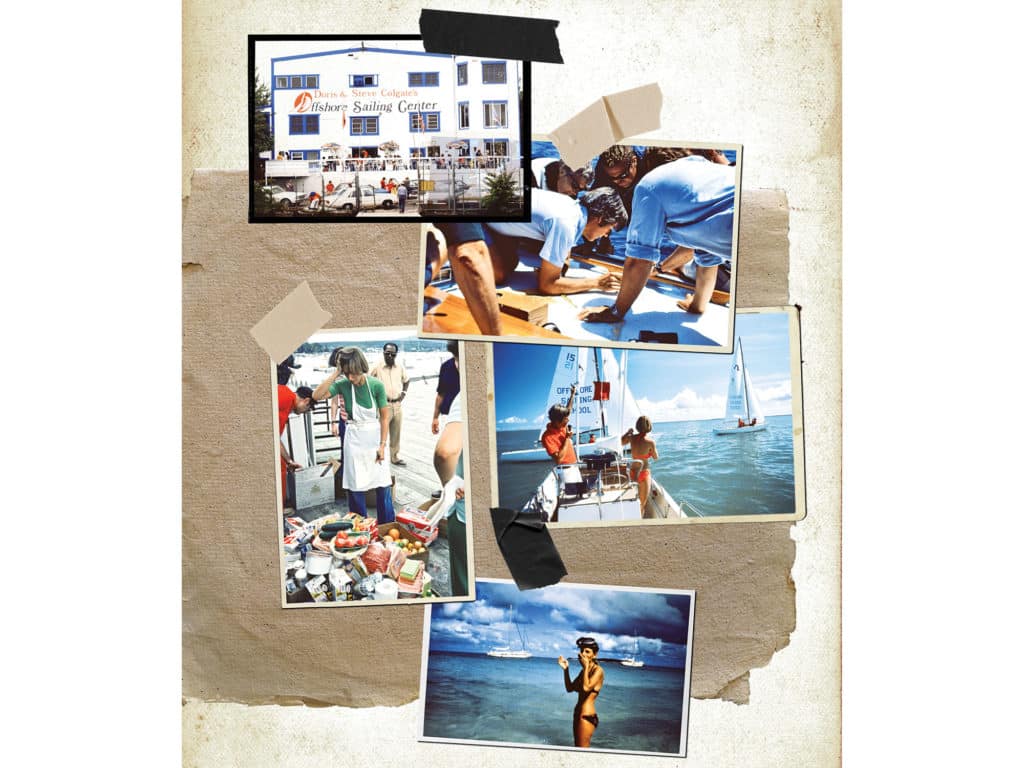

However, it wasn’t just Doris and Steve’s shared love of sailing that fused them, or even their rock-solid matrimonial bonds. No, their partnership extended well beyond shared recreational pursuits and their deeply committed relationship. For they were in business together, a business called Offshore Sailing School.

Quite simply, before everything else happened, it’s how they met.

Steve had started it in New York City in the mid-1960s, after college and a stint in the service, almost as a whim; he was already one hell of a sailor, and it wasn’t like he had something else he wanted to do. Doris had discovered Offshore—and sailing and Steve, all at once—as a diversion from a stifling job and a shaky marriage. Once Steve and Doris were together, they found in their work a nearly perfect complementary balance, a yin and yang to their own best talents and aspirations. Steve turned out to be a natural teacher, with deep knowledge of his subject and an almost intuitive understanding of how to share it. Doris soon learned she had the soul of a burgeoning entrepreneur, and the workaday world at Offshore was also a portal to empowering women and spreading her wings into other fulfilling ventures.

Turner had taken it upon himself to mentor his young tactician, Gary Jobson, and when he saw Steve and Doris, he couldn’t help himself. “The Colgates!” he blared. “Jobson here is going to start a sailing school and run you guys out of business!”

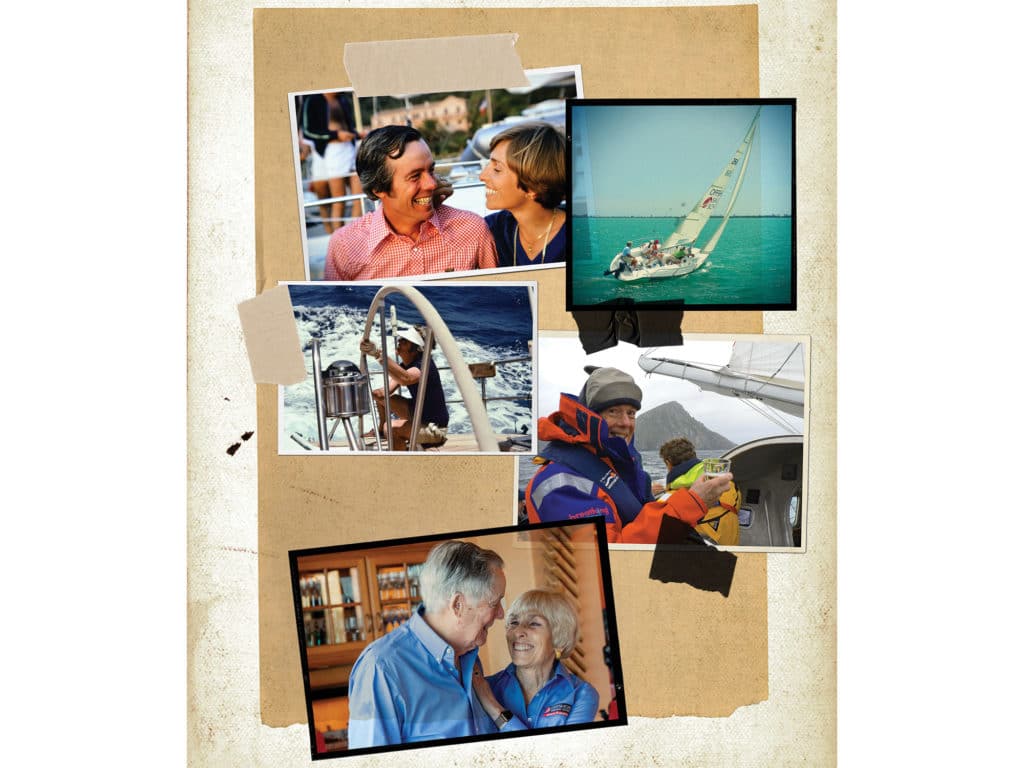

In the final days of the 1970s, having run Offshore together for a decade, they’d built the business into something strong and lasting. Even so, there was no possible way they could’ve had any notion of what obstacles and adventures lay ahead, personally and professionally, in the ensuing decades to come.

Back on the racecourse, in just about every important metric, Steve Colgate was the antithesis of Ted Turner (though Steve had plenty of experience racing against him, and had deep respect for Turner’s gifts as a sailor). Some people find their creative passion in painting or writing or music. Steve found his in racing sailboats, a craft that he honed with the same care, devotion and determination as any accomplished Broadway actor. Steve sailed for neither fame nor money nor notoriety, but for the pure challenges the sport presented him, in all its nuances and competitiveness.

He prided himself on being an amateur competitor, a Corinthian yachtsman, not a professional. When he started racing, there were no such things as pro sailors; the closest applicable comparison was a hired boat captain. These days, there’s a clear professional class of sailors who compete for big paychecks. But when, for example, Steve sailed in the Olympics in 1968, anyone paid to play their sport was automatically disqualified. Steve was every bit as good as any “pro,” but it was a point of pride that he always played for free.

Furthermore, unlike with Turner, there was no spit or bombast in Steve. In fact, one of his attributes of which he was most proud was remaining calm and cool under pressure: There was no screaming or hollering or histrionics on the boats Steve sailed. Which was another way that he was separated from Turner. Over the years of his own prodigious sailing career, Steve had come to the conclusion that skippers who yell in the heat of competition rarely did well. Turner was a rare exception.

Beyond the competitive sailing arena, there was one other big difference between the pair: Turner was a very wealthy man. And while Steve had been born into a noted and successful American family, and enjoyed a rather privileged upbringing, he was now very much a member of the working class. When he started his business, he did have a trust fund, but it was actually kind of an inside joke: a whopping $62 a month. In fact, when he’d launched Offshore in Manhattan back in the mid-1960s, he slept in a tiny spare room in the school’s offices of its East Side walk-up. He couldn’t afford two separate rents.

Two years prior to the Fastnet fiasco, the Colgates had endured their first unpleasant Turner encounter, this time together, shortly after the nicknamed “Mouth of the South” had won the 1977 running of the America’s Cup aboard Courageous, in which he was ably assisted by a prodigal young tactician named Gary Jobson (Turner had stumbled into the winner’s press conference completely wrecked on the bottle of Aquavit that he was still swigging).

A few weeks later, Steve and Doris ran smack dab into Turner and his young protégé, Jobson, at a reception for the Cup defenders at the regal Manhattan headquarters of the New York Yacht Club on West 44th Street. Turner had taken it upon himself to mentor the 20-something Jobson and provide some career advice, and when he saw the couple, he just couldn’t help himself. “The Colgates!” he blared. “Jobson here is going to start a sailing school and run you guys out of business!” (Many years after, Jobson said that Turner was just being his usual “wiseass” and the last thing he ever intended to do was launch a sailing school: “Oh my god, you’d have to buy all these boats, and the insurance, and you’re stuck in one place…I wanted to keep moving and sailing.” Plus, he concluded, “that’s hard work!”)

But Steve and Doris had a difficult time letting it slide. When it came to what they were building at Offshore, it was personal, because they took their business very, very seriously. And now, yet again, here in England, Turner was back at it.

But there in the pub, unfortunately, for all his unnerving bluster and nonsense, even Doris realized Turner had actually raised a couple of very pertinent questions. For instance: How were Sleuth and her crew faring in the tempest?

And then, of course, there was the far more pointed one, for which Doris was pining for the answer: Where the hell was Steve?

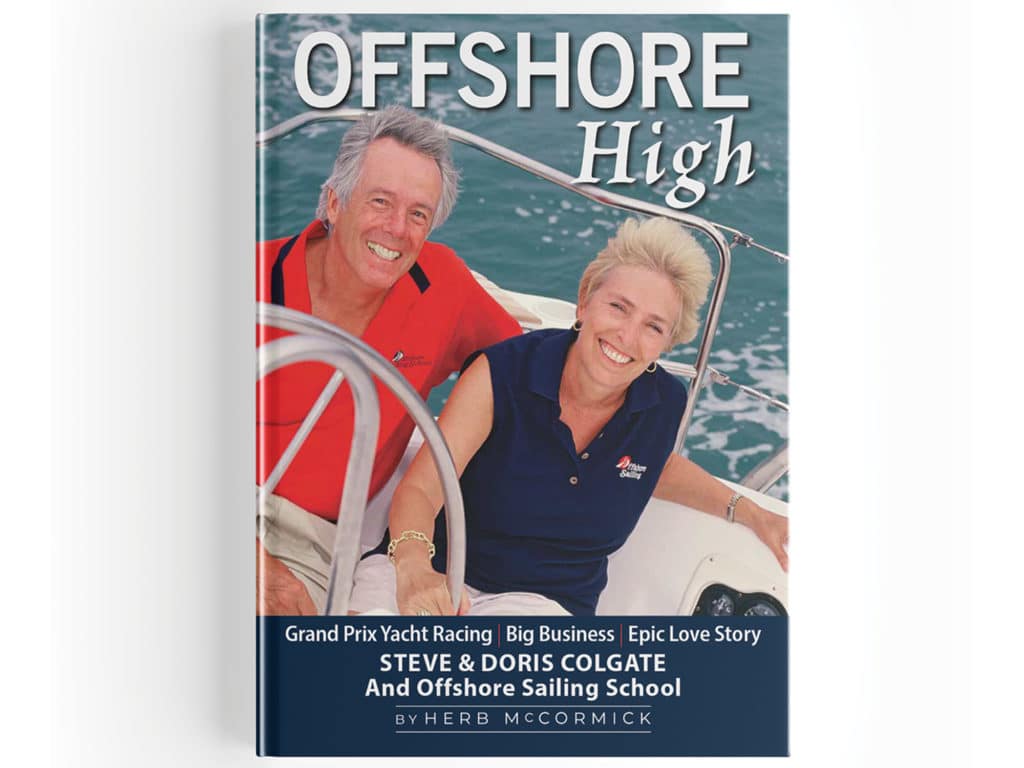

Order a hardcover edition of Offshore High, autographed by Steve and Doris Colgate, at an exclusive rate available only to CW readers. The 288-page book has 177 full-color photographs and makes a fine gift, personalized, just in time for the holidays. Normally $39.95, CW readers receive 15 percent off. Visit offshoresailing.com/offshore-high (and use code CW15OH) to order. Published by Seapoint Books, Offshore High is also available in bookstores and the usual online booksellers.

CW executive editor Herb McCormick is the author of five nautical books, including As Long as It’s Fun, the critically acclaimed biography of cruising legends Lin and Larry Pardey. (Editor’s note: This book excerpt was edited for style and clarity.)