The weather forecast was from a different world from the one we had been inhabiting in the northern canales. If you just looked at the forecast without squinting and imagining, it was hard to see us traveling at all for the next week.

Which would be no biggie, of course.

Except.

Except that our visas for Chile were going to expire in less than a month, and Puerto Natales, the next place where we could cross into Argentina in a single day to renew our visas, and therefore not have to leave the boat unattended overnight, was still far away.

And, there was this thing with our propane. We left Puerto Montt with a stockpile of propane that would last us three or three and a half months in the tropics. But we have somehow gone through three quarters of it in about five weeks.

We weren’t using that much more with all the mugs-ups that were seeing us through each day. Were the tanks under-filled in Puerto Montt? We don’t know. But the idea of being stuck in some caleta days from anywhere, listening to the sleet on deck, with no propane to facilitate the cooking process, was not an outcome that I wanted to entertain.

And the next place where we could hope to fill our US tanks was…that same Puerto Natales, still so far away.

Back when I was an ambitious Alaskan mountain climber of mediocre ability, my ambitious-if-mediocre climbing friends and I would occasionally meet climbers coming up from Outside with plans to climb Denali (Alaska’s 6,000 meter peak) in winter. We’d roll our eyes and shrug our shoulders. Living in Alaska was proof against being so silly as trying to climb the highest peak on the continent in winter.

I’ve long ago decided that sailing to the Land of Fire in winter is not the same thing as trying to climb Denali in winter – i.e., proof that you are both clueless and a show-off.

We have so many friends and acquaintances who have sailed here – some of them in winter – and they’re such normal people. Better sailors than us, for the most part, but still complete amateurs and everyday people, just like us.

For us, sailing south in the winter was never a goal. It’s more or less that we frittered the summer away on one thing and another, and it seemed a better idea to get going south when we were ready, rather than to sit in the marina in Puerto Montt all winter, waiting for a “better” season. And besides, if those people we knew had done it, etc., etc.

But, in the dark night as we were dashing around at the end of the anchor chain in Caleta Ideal, it was all starting to seem a bit…adventurous.

We took more than an academic interest the next day when we shoved off to sail down Canal Messier. Could we, you know, travel in the conditions that presented themselves?

That was one of the most stirring sailing days we’ve ever had. Nine knots through the water under staysail alone isn’t our normal sort of outing.

It was such a stirring day that we didn’t get any pictures at all.

The weather was supposed to go from nine-knots-under-staysail-alone to completely shitting itself mate, to quote one of my better-spoken Tasmanian friends. So we were very happy to execute a four point tie-in before dark.

And so we’ve established something of a rhythm. Some days we don’t travel, but we’re happily surprised that we are able to most days.

And though I’ve decided that people who sail to Patagonia and then talk about the weather are in the same category as those people who live in Alaska and complain about the cold winters, it is hard to escape the physical conditions if I’m trying to give some impression of the place. How dark it is when we wake up. How the rain is cold enough to feel like a different element from the water we’re used to. That sort of thing.

We’re also getting well into the routine of tying into shore every night. We know some other Patagonia newbies who express various degrees of skepticism about tying in, or who try to tie in only when they are forced to.

We figure that until we know what the hell is going on, we’re going to act like our friends who know a lot more than us and tie in every night – with four shore lines if it feels like at all a good idea. Weather surprises do happen, and I figure the night will come when we’re very glad to be defensively set up. And the practice of doing this every night can only help when we come to a situation when finding a safe berth isn’t straightforward.

A Single Piece of Petrel Down

At the anchorage where we finished the crossing we met Patrick, a singlehander on Cephalais II. He had been sitting in Caleta Ideal for a week, waiting for a chance to cross to the north, with only the short-range forecasts relayed by the San Pedro lighthouse to guide him.

Patrick was finishing a tough trip from the south. In Punta Arenas a wind shift left his boat exposed to the full fury of the Straits of Magellan while he happened to be ashore dining with a friend. Repairs took two months.

Our second night in Ideal felt insecure. The rig shuddered and the boat swung. Although we have a very good anchoring setup, we would prefer to be tied to shore in some little nook rather than swinging in the gusts.

Leaving Ideal was a difficult decision. We were conscious of our inexperience in these waters, and the golden rule of never leaving a secure anchorage in bad weather. After we picked the hook Patrick followed, acting on his decision to go wait in the village of Tortel for a while.

We fairly flew down Canal Messier, the main north-south route in this part of the canales. Nine and ten knots through the water, with the opposing tide bothering us not at all. Alisa kept me company under the dodger with its made-for-Patagonia back door/rain shield. No school, and the boys were for (literally) the first time in our sailing career abandoned to the electronic nanny of the iPad. They watched the French cartoons that I downloaded in my failed campaign to turn them into little Francophones.

That was last season. This season I’m concentrating on my failure to turn them into Spanish speakers.

I haven’t seen this many shades of gray since the Aleutians, said Alisa.

Giant petrels swooped behind us. A single piece of petrel down went scudding across the waves, passing us in the wind.

We declined the offer of the first three good caletas we came to. We’re out here, traveling fast, I reasoned. No reason to stop. We came to rest in Caleta Morgane, a little nook surrounded by absolutely primeval rainforest. A creek pours foam and tannin into the ocean just off our stern and four shore lines hold us exactly where we want to be.

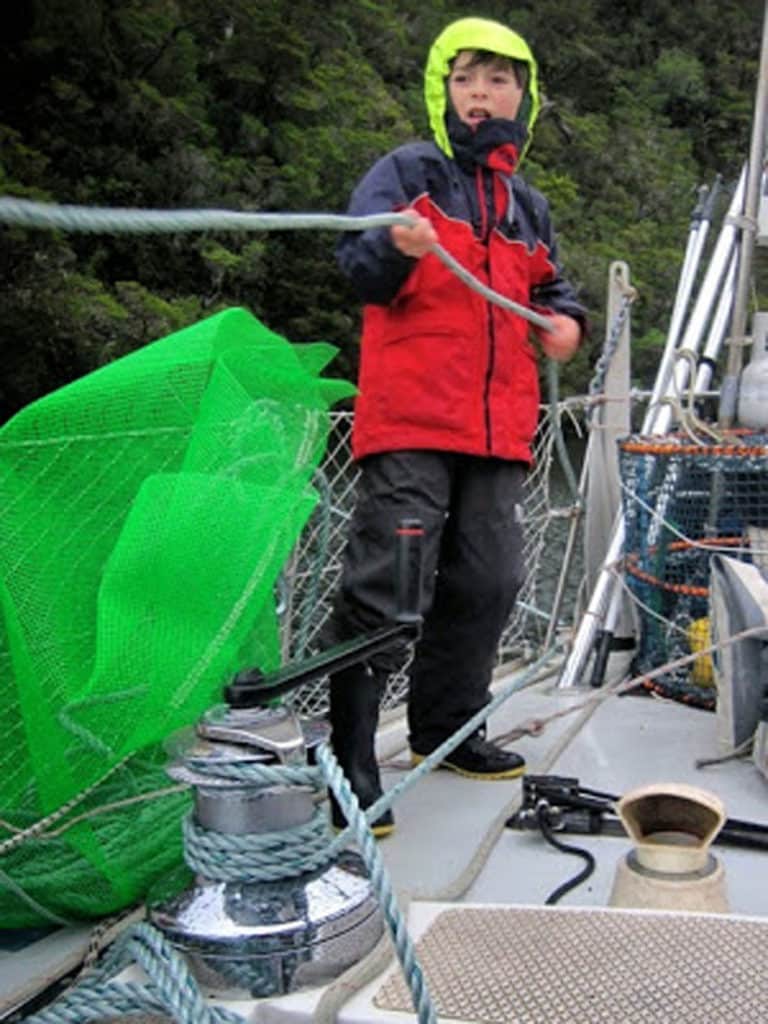

Elias helped with the lines, pulling out slack for me while I rowed them ashore. He shouted not-quite-to-the-point questions and misheard my replies. The diesel stove warmed us all up and Alisa made green chicken curry.

After the boys went to sleep we recapped the day. We just need to keep making good decisions, I said. We’re learning so much every day.

When we left Alaska to sail to Australia with our toddler for crew, we thought it was a once-in-a-lifetime thing. But then we had our second child, and bought our second boat, and sailed across the Pacific a second time. We’ve been living aboard for seven years now. Sometimes we wonder how long we’ll keep at it, but all we know for sure is that the end doesn’t seem to be in sight just yet. Click here to read more from the Twice in a Lifetime blog.