Sail enough offshore miles and the glories of driving dwindle, especially when the first splatters of a Pacific Northwest rain or Down East fog start peppering the hood of your foul-weather jacket. Then, the thought of a warm cabin, of hot coffee and warm soup, sounds fantastic. Enter the modern autopilot, a powerful tool for both bluewater and coastal cruisers that offers the opportunity to reef, hoist or lower sails without waking the off watch, while freeing up the single- or shorthanded sailor to attend to navigation or other chores when underway.

Modern autopilots use a manageable amount of electricity compared to their predecessors, making them a strong option for backing up a windvane installation, or for use as a sole mechanical driver aboard boats that have adequate wind- and/or solar-power systems (or hull forms that aren’t easily fitted with windvanes). During prolonged passages, autopilots are far more efficient than human hands, as their DC-powered brains ensure a never-swerving attention span. Let’s look at the nuts and bolts behind today’s steering systems, from their supporting hardware and technology to cutting-edge features.

Intelligence by Design

The world’s first gyroscope-guided autopilot — nicknamed Metal Mike — was developed in the 1920s by Elmer Sperry to mechanically steer large vessels, including U.S. Navy warships. While Metal Mikes performed fairly well, they were far too bulky for recreational craft, so sailors had to wait until British-born inventor Derek Fawcett introduced his Autohelm in 1974. This tiller-mounted, stand-alone system drove the boat to a user-determined apparent-wind angle using a hydraulic arm, an external windvane and the house battery. Fawcett’s later innovations included an internal gyrocompass, allowing sailors to set their course based either on wind angle or compass information, and a user-friendly analog keypad that included commands for “Auto” and “Standby,” as well as direction options such as +1 degree or -1 degree, and +10 degrees or -10 degrees — all of which would look familiar to contemporary sailors.

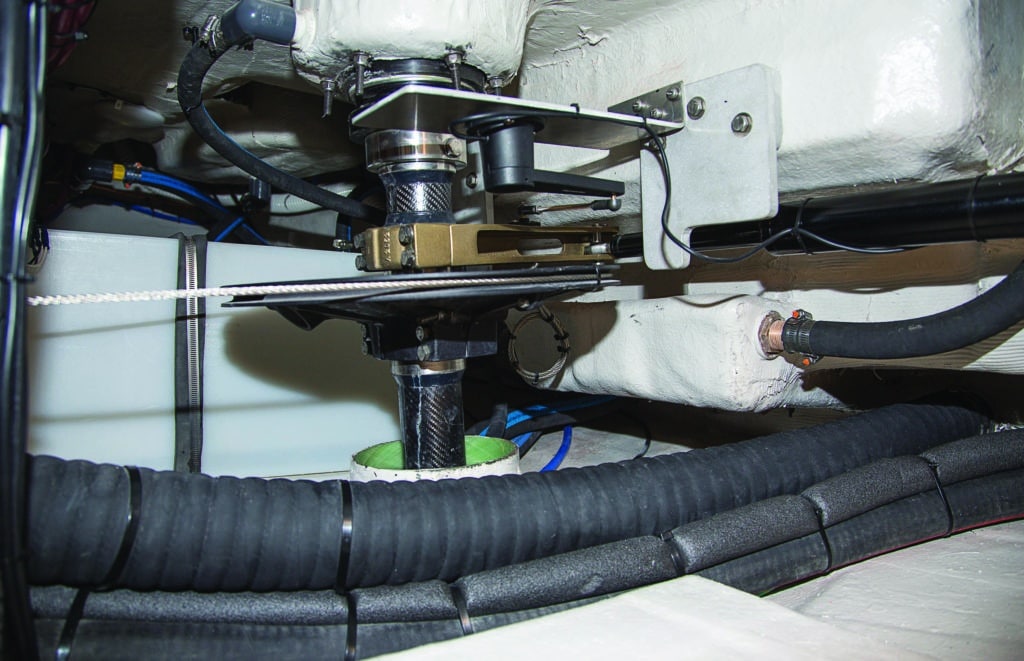

Today, autopilots are typically comprised of three main components: a black box that acts as the system’s brain and power supply; a control head that provides the user interface; and a drive unit, which serves as its muscle, typically powering either an electric or hydraulic ram connected to a tiller bar on the rudder stock. Together, these components create an electromechanical system that can operate as a stand-alone installation or be networked with the vessel’s navigation system via an NMEA 0183, NMEA 2000 or proprietary connection for increased functionality. When networked, heading information and rudder angle can be displayed on a chart plotter or other multifunction display (MFD).

Autopilots commonly use proportional-integral-derivative (PID) controllers, which act as part of the black box’s brain, constantly looking for variations between the user-determined course and the boat’s actual heading in order to make course corrections. The autopilot’s goal is to maximize vessel efficiency by minimizing rudder movement, using complex software algorithms that constantly test the vessel’s position and heading and govern the PID controllers accordingly.

Provided that an autopilot is networked to the vessel’s MFD, position data is available from the GPS; however, most stand-alone autopilots have traditionally relied on fluxgate compasses (effectively a metal ring floating in an oil bath) as their heading sensors. While accurate, fluxgate compasses are sluggish compared to today’s lightning-fast processors.

“Up until this generation of autopilot, the heading sensor was the worst part,” says Jim McGowan, Raymarine’s marketing manager. He says that fluxgate compasses are prone to shaking and vibrating with the boat. “Older systems didn’t have the level of smarts to stay calibrated in big seas. Also, fluxgate compasses are magnetic-based, so they’re sensitive to onboard gear and tools, which can create a deviation,” he adds. Because of this, some current-generation autopilots use either built-in solid-state sensors or solid-state sensors that are networked with external instrumentation.

“Our new sensor still has a magnetometer, but it’s on a chip, along with sensors for yaw, pitch-and-roll and rate of turn,” says McGowan in reference to the nine-axis EV1 heading sensor, which serves as the heart of Raymarine’s Evolution-series autopilots.

Other manufacturers have taken similar tacks. “For our Reactor series, we added an AHRS sensor,” says Dave Dunn, Garmin’s senior manager of marine sales and marketing, referring to the attitude and heading reference system that Garmin incorporated into its autopilot line in 2015. “It compensates for heel and pitch-and-roll, and it reduces oversteering in rough water.”

While B&G’s Triton and H5000 systems use a gyrostabilized compass (a fluxgate compass with a rate-of-turn sensor) and other instrumentation rather than solid-state sensors, depending on the model, the company uses advanced algorithms to provide gust and anti-broach control and to deliver motion-controlled wind information by removing induced wind data.

“We’re not looking at one sensor to provide everything,” says Matt Fries, B&G’s business acquisition manager. “We measure boat speed, rudder angle, static heel and static trim individually, as well as heading and rate of turn from the compass. On the more advanced systems, we use a three-axis rate sensor in conjunction with the instrument system to filter out noise in the wind data, accounting for the induced wind from the motion of the vessel.”

Part of the Network

Typically, autopilots are sold with a dedicated control head, but most modern autopilots deliver enhanced features when they’re paired with a networked MFD, allowing the autopilot to access real-time position data and wind speed and angle information, and (depending on the system) to connect to Wi-Fi. “We added software features and capabilities that are designed to be expandable from the get-go,” says McGowan about Raymarine’s Evolution autopilots. “We also added sailing-specific features in our MFDs that add utility to the autopilot and tie the system together to hold the boat on course.” System depending, networking the autopilot to the MFD can enable the autopilot to “see” its next waypoint (rather than relying solely on heading information), allowing the pilot to make “smart” course corrections. For example, some modern autopilots offer a no-drift function that, when paired with the GPS, takes into account leeway due to wind or tide, and that steers accordingly to ensure a proper course. This is especially useful if the MFD can access real-time weather and tide information. Also system depending, networking an autopilot to an MFD can allow a user to eschew a dedicated control head altogether.

Built-In Versatility

The final important component is the drive unit. Manufacturers commonly buy drive units from third-party vendors rather than building proprietary units. This can be a great benefit for consumers, as depending on the system, it can allow them to upgrade their legacy autopilot systems with new electronics, or to switch autopilot manufacturers without having to tear apart their drive system. While autopilots for smaller sailboats typically attach to the tiller or the wheel, larger vessels usually require a quadrant-mounted system. In all cases, it’s important to select a drive system that can handle your boat’s fully loaded cruising displacement.

Sailboats generally use a mechanical drive system that’s selected based on the boat’s displacement, says McGowan. Buyers need to keep in mind that the boat’s light-ship displacement, the weight often cited in sales brochures, doesn’t account for cruising gear. To compensate for creature comforts, McGowan recommends adding 20 percent to a vessel’s displacement to account for additional diesel, water and blackwater tankage, as well as anchors, chain, tools and other essentials. “If the drive unit is too small to handle the weight of the boat, it has the potential to fail at the worst time,” he says. In addition to maintaining an efficient course, modern autopilots typically offer advanced steering options, ranging from man overboard (MOB) recovery routing to modes that hold the bow into the wind. Additionally, some manufacturers offer “economy” and “precision” driving modes, which are important for, say, long, windless passages, or when navigating a constricted channel. When operating in economy mode, the system will accept a greater cross-track error in order to reduce power and fuel consumption, while the precision mode ratchets down cross-track error but requires more active rudder management.

One particularly interesting option involves MOB situations. “The optional radio remote control turns the pilot into a fully automatic MOB system,” says Bob Condon, NKE’s U.S. national sales manager. “If someone goes overboard with a remote, the system will fire off alarms. The system can be configured with a VHF to send distress calls, and it will even put the boat head to wind to give a solo skipper the chance to get back on board.”

Given that most MFDs now offer Wi-Fi connectivity, it’s possible to control some autopilot systems via a third-party smartphone or tablet. Here, it’s important to note that some marine-electronics manufacturers view autopilot controls as safety equipment, and are therefore hesitant to relinquish heading control to a third-party device.

“We don’t allow our systems to be controlled via devices, only from a dedicated B&G remote control,” says Fries. “We don’t want a 12-year-old kid changing waypoints on a tablet. There’s a lot of liability involved, so we want people to control the autopilot with full situational awareness.”

Raymarine shares a similar philosophy, although McGowan hints that this barrier might eventually drop. Other manufacturers take a different approach, as Furuno, Garmin and NKE allow their customers to control their autopilots using a smartphone or tablet that’s running a proprietary app, provided the autopilot and MFD are built by the same manufacturer. (Other hardware requirements may exist, system depending.) And while most manufacturers also build proprietary remote controls, Garmin users can also wirelessly control their autopilots using a Garmin Quatix watch, which works as a wearable remote.

Historically, after all components have been installed, autopilots have still required significant amounts of compass calibration and vessel-specific setup to function properly. This is evolving, however, thanks to the current generation of processors, better heading sensors and improved algorithms. The result is a new class of autopilots that offers quick setups or even automatically “learns” your vessel’s steering characteristics, without user input. Raymarine’s Evolution autopilot sports its proprietary Automagic feature, which uses plug-and-play connections rather than lengthy calibration processes. “It’s auto-calibrating, from the box to use, without having to turn circles,” says McGowan. “As you navigate, the system continues to calibrate. It looks for the rate of turn, and it builds a performance table for the boat.” Also, says McGowan, when the Evolution system is networked to a GPS, it can automatically calibrate itself magnetically for different latitudes.

Likewise, Furuno’s NavPilot autopilots also use self-learning software. Eric Kunz, Furuno USA’s senior product manager, describes the setup as being “pretty painless.” He says, “With our autopilots, you just bolt it down and you’re done. Just put the autopilot in auto mode, and it’s set-and-forget.”

Not everyone agrees that autopilots can deliver the same results via a self-configuration process. “We don’t believe in zero commissioning,” says Garmin’s Dave Dunn. He adds that it’s almost impossible for an autopilot to work without some externally entered parameters. That said, Garmin’s latest systems take only about five minutes to calibrate.

B&G takes a similar approach. “Our systems have some self-learning and auto-tuning capabilities, but someone who spends the time to properly set up his or her autopilot will experience better results,” says Fries. “I don’t believe that anyone — including B&G — has self-learning algorithms that will achieve the same performance levels attainable by some experienced tweaking. Setup still needs human brains; it’s a bit of an art.”

Steering systems have come a long way since the days when naval navigators relied on Metal Mike to get from here to there. Choose the system that’s properly sized for your boat and that works in sync with your navigation gear, and odds are excellent that you’ll enjoy years of hassle-free cruising — provided, of course, that you download and install the latest software updates, and that you occasionally inspect your drive systems. Otherwise, modern autopilots stand ready to dramatically simplify your helm work, affording you and your crew enhanced comfort when Mother Nature gets scrappy, or when it’s more fun to socialize than it is to chase numbers on a compass card.

Autopilot Manufacturers

B&G, bandg.com,

603-324-2042; from $1,850.

Furuno, furunousa.com,

360-834-9300; from $3,370.

Garmin, garmin.com,

800-800-1020; from $2,050.

Humminbird, humminbird.com,

800-633-1468; from $2,000.

NKE Marine Electronics, nke-marine-electronics.com,

401-849-0060; from $5,400.

Raymarine, raymarine.com,

603-324-7900; from $2,000.

David Schmidt is CW’s electronics editor.