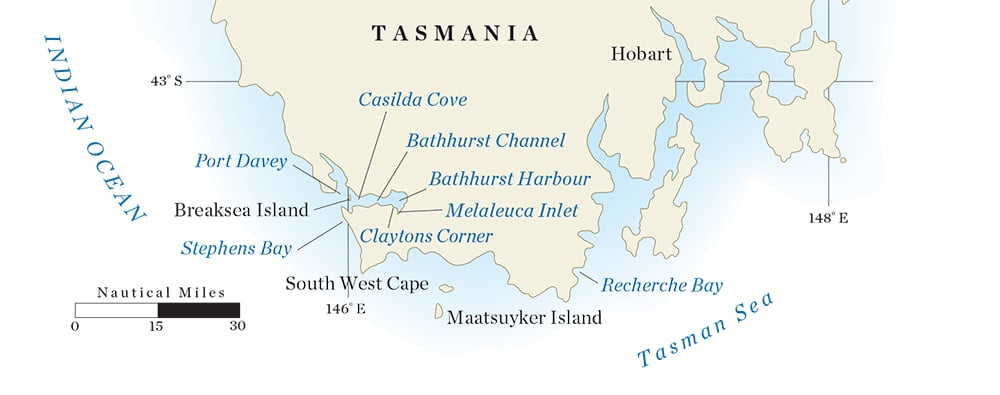

A s the steel bow of our Tahiti cutter Beatrice surged into the swells, at the helm I felt a long way from the milder climes of mainland Australia as the foreboding mass of Tasmania’s South West Cape loomed large on our starboard bow. The Pilot book describes a voyage to “Tassie” as the Ultima Thule of Australian cruising so my cousin, Christian, and I had spent a year planning and keenly anticipating this three-week summer trip that would require about 300 nautical miles of sailing. We were amidst the fabled Roaring Forties with very little shelter along Tasmania’s unpopulated southwest coast.

The previous day’s passage down the sheltered east coast from our departure point at the Oyster Cove Marina, near the island state’s capital of Hobart, took us through a pristine cruising ground that’s protected from the Pacific Ocean swells by a series of barrier islands. Gleaming beaches, secluded anchorages, welcoming ports and marinas dotted the tree-lined coast. Tasmania is famed for its marine industry that includes wooden-boat building and, of course, the famous 640-nautical-mile Rolex Sydney to Hobart Race, which I’ve enjoyed competing in. Hobart’s biennial Wooden Boat Festival is another major reason to sail to this wild and largely unspoiled region.

In any case, the initial stretch of the trip, in light northerly winds, was uneventful before we sidled into the sheltered anchorage at Recherche Bay to conclude our first day of sailing. Its name — like many others in the region including the barrier island of Bruny — was given by the early French explorer, Captain Bruny D’Entrecasteaux, in 1793. Another notable Frenchman in the island’s history was Nicolas Baudin, who created the first entire chart of Australia during his voyage in 1800. Christian, who speaks French, particularly enjoys Tasmania’s French Festival week where these connections are celebrated, though most of the island’s population descends from former British convicts. Unlike the British colonizers, the French had been mostly scientists and discoverers.

Diving off Beatrice into the cold clear waters of Recherche Bay, I swam down to the sandy bottom to check our anchor and scrub some weeds off the steel hull of our 32-footer before our evening meal and bed. We would have an early start to pass South West Cape the following day.

Into the Wilderness

In planning our voyage, Christian had been diligently watching the Bureau of Meteorology website for weeks, so he knew our window of opportunity was tight for the 70-mile leg from Recherche to Port Davey. North of Port Davey lay the old penal settlement of Macquarie Harbour, but its entrance name of “Hell’s Gate” suggested a precarious welcome. Alas, we could not be going there on this trip.

After overnighting in Recherche, we motorsailed off at sunrise to dodge yet more crab boats as we sped south on calm seas, bound towards South West Cape, leaving our last mobile phone access point behind. Before too long, we passed Australia’s southernmost lighthouse on Maatsuyker Island, where we encountered the first of the bull kelp beds. The 10-meter long stalks reached up from the seabed and seemed determined to entangle Beatrice‘s prop. Perched on the long bowsprit, I directed Christian beyond them.

We passed bays and tall cliffs until the peak of Frenchman’s Cap glistened in the growing sunshine, with the brooding mountains of the World Heritage-listed South West Wilderness region beyond. This had been the last bastion of Tasmania’s indigenous peoples — the Needwonee and Ninene — until the arrival of white explorers and latterly tin miners in 1892 at a bay off our starboard bow named Cox’s Bight.

Albatrosses arrived along with a pod of dolphins to escort us around South West Cape, its gray headland giving way to low, lying cliffs that ran almost uninterrupted for 14 miles to the entrance of Port Davey. A dangerous lee shore in any kind of southerly or westerly wind, it was not a place for sightseeing so we kept our tan sails full and Beatrice moving along under full sail: jib, staysail and main.

Closely watching my Navionics chart, I piloted us past the outlying Pyramid Rocks at the Port Davey entrance. The charts showed reefs all around so it’s a dangerous place in a swell, but the calm of our arrival showed the tranquility of this surreal landscape of glistening quartz headlands, shiny white sea stacks and green tidal reefs. A small shark swam by us and then several seals emerged to stare forlornly at the interruption to their wild seascape. Shearwaters sped past and pied cormorants stood sentinel on the outlying rocks as we glided toward Spain Bay, the first anchorage. Our peace was interrupted by a static hiss from the VHF radio and then the clear and friendly voice of Tas Maritime, giving a mild weather forecast for the following days. In addition, we also had our Sony SSB receiver hooked up to a whip aerial which gave us weather reports from the mainland.

Uncharted Waters

Looking closely at my Navionics charts and the corresponding Australian paper charts showed large amounts of “unsurveyed” patches throughout the hundreds of square miles that make up this sprawling waterway, with only a sole light on Whalers Point near the entrance. First surveyed in 1820 by John Oxley, who concluded “the whole navy of Europe might ride in safety from every wind,” Port Davey became the major logging area for the coveted boatbuilding wood Huon pine, along with celery top and lesser varieties. When tin was found, commercial interest grew strongly and the “nuisance” of the indigenous tribes was removed by Governor George Arthur’s decree of 1826 that aborigines could be legally killed. This led to the infamous Black Line of militia that crossed Tasmania to remove the remaining indigenous population. This bloody history has erased most indigenous culture from the area apart from some cave paintings and the many large middens testifying to 35,000 years of a people that was so hastily removed. Hiking over from Spain Bay to the ocean side at Stephen’s Bay brought me to several large middens where shells and whale bones were seen.

RELATED: Tasmania: The Best for Last

Also marked on the chart were the many wreck sites, which told another sad history about sailing ships running down their easting from the Indian Ocean on the prevailing westerly winds. Unlike the sextants used for latitude, the timepieces required to calculate longitude weren’t accurate so many a ship smashed into this wild coast as it overran its intended course toward Asia. One of the worst wrecks was the square rigger Briar Holme in 1905, which drowned nearly all aboard apart from a few who came ashore to die of hunger. The only survivor was a man named Oscar Larsen, who survived 100 days in the bush before a fishing boat found him.

Passing Bramble Cove, we could see the main shelter for larger vessels including whaling ships; the small, adjacent graveyard tells another grim story, as the stark vegetation and lack of wild fruit meant little sustenance for shipwrecked mariners. However, indigenous knowledge would have revealed edible roots and other bush tucker, but by then the indigenous people were long gone. Eventually government provisions were stashed and rabbits introduced to sustain shipwrecked sailors. During my hikes over the mountains and dense Melaleuca-clad meadows, there was no sign of them — only wombat tracks and wallaby droppings. Still, I walked warily in case the snakes called death adders lurked. Perhaps the rabbits were all eaten by the majestic sea eagles that soared above me.

Rugged Port Davey

Two large waterways comprise this mountainous region, which is a marine reserve and a World Heritage area. These are the ocean bay of Port Davey and the landlocked Bathurst Harbour, which is reached via the fairly deep Bathurst Channel. Its dark-brown waters are fed by the rivers from the peat clad hills. Exploration required heavy use of our 20 hp Bukh diesel until one day, while at anchor in Schooner Cove, it emitted a loud groan followed by a plume of black smoke. The sudden horror of being engineless — and several days from the nearest habitation — dawned on us as we quickly looked over the smoking red engine. Our noses followed the scent of burnt plastic to the Bosch kill switch. On cranking the engine we discovered, to great relief, that it started but, of course, wouldn’t stop. However, a long pull on the decompression lever returned Beatrice to silence, and we celebrated with two nips of Johnny Walker.

Climbing Balmoral Hill one sunny day I met some more of the local fauna: the pesky March flies, a persistent type of horsefly that continued biting even when swatted. Their stings were somewhat soothed by the view, which showed a rugged vista of rocky headlands and bays running west to Port Davey; to the east lay secluded yellow beaches and the narrowing channel that opened to the 5-mile-wide Bathurst Harbour. The unpolluted air allowed for long views with even the saw-toothed Arthur Ranges in sight. The northern view was dominated by the towering 2,500-foot peak of Mount Rugby. As the weeks passed, it would be my navigation beacon when hiking or buzzing around in our inflatable dinghy.

Exploring by yacht proved precarious, as our foray up the northeast corner of Bathurst Harbour brought us to a sudden halt on the white part of the chart again declared “unsurveyed” near Old River. While cursing John Oxley for a job unfinished, I hastily clambered on the out-swung boom after realizing we were on a falling tide with 10 tons of Beatrice resting her long keel on hard peat. An impersonation of an irate Tasmanian Devil followed as I danced on the boom to tilt Beatrice while Christian gunned the smoking Bukh to free us. Yet more Johnny Walker followed to calm the nerves and soothe the March fly stings.

Stormbound!

Hiking one day among the foothills of Mount Rugby along the Port Davey track — the only way into this region from the populated part of Tasmania — I noticed clouds gathering to the southwest as I rested for lunch overlooking Joe Page Bay. I was about to feel the fury of the Roaring Forties but little did I know how quickly it would arrive. Hastily, I made my way back to the dinghy on the small beach at Farrel Point and set off for the 2-mile dinghy ride back to Beatrice. After reaching the boat at Frogs Hollow Bay, it was not long before we heard the first howl, as the wind front crashed over the trees to knock Beatrice over nearly to her gunwales.

The falling barometer confirmed the change in the weather, so in the lull the following morning we sought better shelter and anchored deep into the mud at an anchorage called Claytons Corner. Then the real might of the storm was felt with gales and rain. Nearby Maatsuyker Island reported 74 knots. Braced in the forepeak bunk, I pensively listened to the groan of our 120 feet of chain and line as 50-knot gusts slammed into us. February in Port Davey felt very different from mainland Australia, where Sydney basked in 86-degree sunshine while we shivered around our charcoal heater as temperatures plummeted.

Of the half dozen boats that were cruising the region, most took shelter nearby at Kings Point or in the more protected Casilda Cove. Water is never a problem with rivers flowing all around, and the Claytons and Waterfall Cove offer clean, fresh water. However, our homemade sauerkraut and tinned food began to pale after day four. By then, the second bottle of Johnny Walker was as dangerously low as our barometer. To pass the time we yarned plenty about life and families, to whom we sent messages and position updates via our Spot satellite tracker. I read my way through Christian’s library and particularly enjoyed Christobel Mattingley’s King of the Wilderness, about tin mining and the wildlife pioneer Deny King, at one time the region’s only inhabitant.

However, with cabin fever growing, we eventually tried our first escape from Port Davey, sailing out to meet 20-foot combers rolling into the swell-covered bay. The old sailing ships would have been embayed but the Bukh took us away very slowly as Beatrice‘s deep bulwarks disappeared into green water. Worryingly, we realized the wind would put us on a lee shore on the leg to South West Cape. The time was ticking by for us to make a decision, as the only port of refuge at Spain Bay was downwind, so we waited for a lull and put the helm down to turn around and tuck into its protected anchorage. It would be another four days before the weather turned in our favor, releasing us from what was a most memorable and adventurous visit to the well-named Ultima Thule of Australia.

When not traveling the globe, Australian yachting journalist Kevin Green can be found sailing his 43-year-old Contessa 25 off his mooring in Sydney’s Iron Cove.