For adventurous sailors, the northern Antarctic Peninsula is one of the world’s last unspoiled cruising grounds. Last February, I was part of a group of eight who chartered Pelagic Australis, the 73-foot aluminum sloop designed for high-latitude sailing expeditions by Skip Novak, legendary long-distance sailor and mountaineer. Brawny as its owner, rugged and equipped with a big Cummins diesel, Pelagic Australis is cutter rigged with genoa, yankee and staysail, all on roller furlers with lines leading to the cockpit. The 800-pound mainsail carries four reefs and can be reduced to the size of a handkerchief.

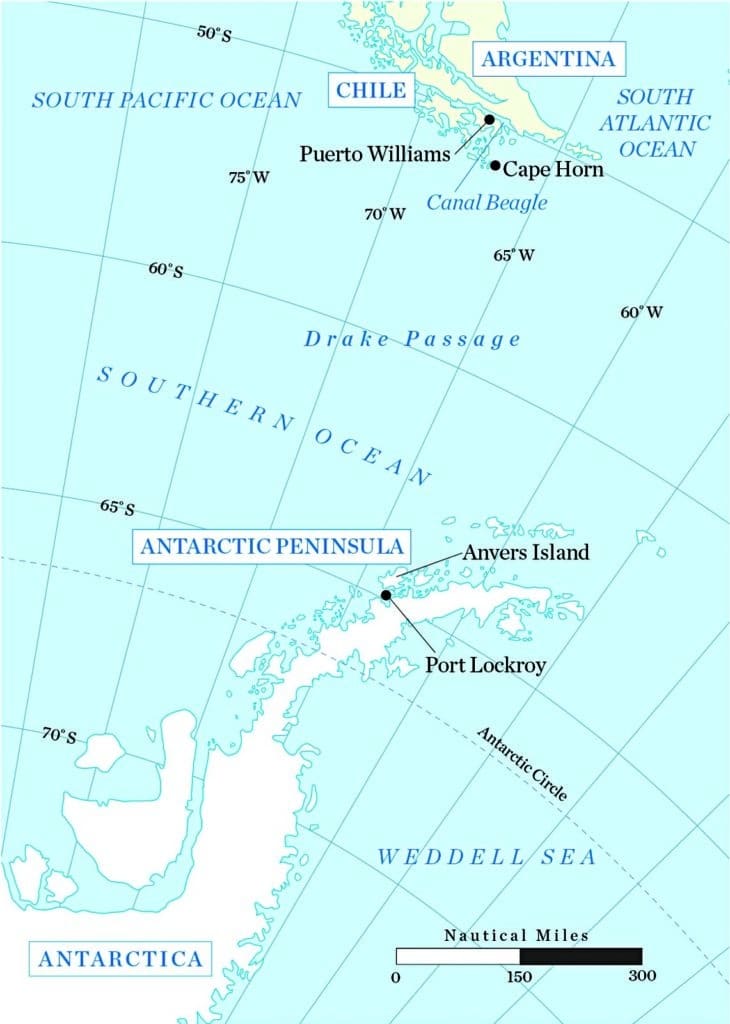

We spent more than three weeks crossing the turbulent waters of Drake Passage, threading our way among icebergs and islets along the Antarctic coast and then recrossing the Passage via Cape Horn.

The cruise started in Puerto Williams, Chile, on the Beagle Canal. We met Pelagic Australis tied up at the Micalvi, a grounded Chilean navy supply vessel that serves as the Puerto Williams Yacht Club.

Soon enough, we were underway on a 650-mile crossing of Drake Passage, one of the most inhospitable bodies of water on Earth, known for its large and unpredictable seas and successions of storm-laden lows. We dosed ourselves with Stugeron, the powerful motion-sickness medicine. The weather gods were good to us. Although some of us were a bit green at various times, we all made the four-day passage without losing our cookies.

Our Antarctic landfall was Deception Island, a sunken crater once the site of whaling and sealing stations, now abandoned and desolate. There, in Whalers Bay, we experienced our first Antarctic storm. During the day the wind increased to the 50s with gusts over 65 knots. Our anchor and 350 feet of heavy chain couldn’t hold us on the narrow shelf under the crater wall. By nightfall we were idling under power in the middle of the caldera. As we drifted to leeward, once in a while one of us had to go out in the cockpit, rev up the engine and drive the boat to windward to gain drifting room. Then we could sit tight again. It was a long night.

But storms pass. A day later we were nosing south among snow-crowned peaks on islands and mainland, nudging small icebergs and spotting seals, whales and, of course, penguins in abundance. We launched the Zodiac and a couple of kayaks to explore.

Our first major destination was Port Lockroy, a former British research station on tiny Goudier Island, in front of the large glaciers of Wiencke Island. The huts of the former research station are now a museum, a post office and a gift shop managed by the Antarctic Heritage Trust. Port Lockroy is a mandatory stop for cruise ships along the Antarctic Peninsula each summer. The proceeds of the gift shop support the historic-preservation program in the peninsula region.

From Port Lockroy we pushed south along the west side of the peninsula, through the “iceberg graveyard.” The might of the crags, the whiteness of the snow — everywhere — and the extraordinary blues and greens of the icebergs made us gasp.

Our next destination was Vernadsky Research Station in the Argentine Islands, south of Anvers Island. Vernadsky is a prized destination for Antarctic sailors because it’s the site of the world’s most southerly bar, the Vernadsky Station Lounge. We brought our own wine, but ended up drinking locally produced vodka with our Ukrainian hosts.

While at Vernadsky, an approaching low required us to tie up in a tiny cove on a nearby islet. Pelagic Australis has four large reels of Spectra cable to secure the vessel to boulders on the shore. Four corner ties plus the anchor make a classic Antarctic five-point moor, which kept us safe from winds of 40-plus knots. Although the Spectra lines were taut as bowstrings, they held.

The five-day trip back across Drake Passage to Puerto Williams was enlivened by a near collision with an iceberg on our first night out, and a race to shelter behind Cape Horn to beat an approaching low, which kicked up quite a wind and sea at the end. Par for the course with Antarctic cruising.

Peter L. Murray has cruised Serendipity, his 30-foot wooden schooner, along the Maine coast for nearly 50 years.