PassageWeather

I remember days in my Washington, DC life when I’d leave my climate controlled office wearing a light jacket, surprised that cold, gusting winds were blowing snow flakes around my head.

“Christ!” I’d say to a bundled-up coworker, “I didn’t know it was going to snow today; it was pleasant yesterday.”

“They announced it on the news last night.”

“Huh, I missed that.”

Those days are gone. I can’t think of a lifestyle that would keep me more in tune with the weather than the cruising lifestyle. Windy and I often know what the conditions are where we are and what they are at a weather buoy twenty miles offshore. We usually know the forecast for the next ten days and how that forecast has evolved over the past 48 hours. When we’re passage planning, we look at the forecast twice a day—covering a 500-mile stretch of coastline. Planning two trips across a shallow inlet in King Salmon recently, we could tell you on what hour the high and low tides fell those days. Will there be moonlight on the nights of that upcoming passage? We know.

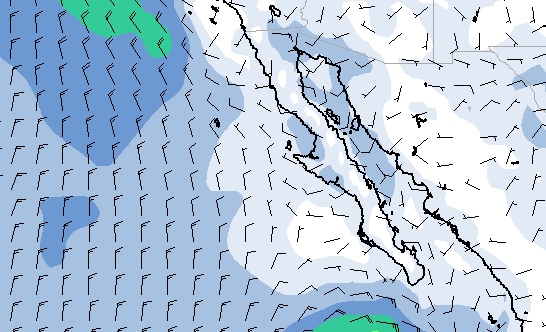

And the nightly news is no help in our pursuit of weather info. For the past year we’ve used www.passageweather.com and the features of the Navimatics navigation app on our iPad. Using PassageWeather.com, we select an area that encompasses our route and then can watch an animated 7-day wind forecast for that area. It has proven to be extremely reliable and we depend on it. From the Navimatics app, we are able to query data from specific weather buoys (data from buoyweather.com) en route that provide real-time local wind data that reaffirms the PassageWeather info, as well as wave heights that let us know what kind of a ride we can anticipate. Too we use other sources and our VHF radio weather channel broadcasts that are available along the U.S. coast.

I’ve always heard how difficult it is to predict weather, how the ever-increasing speed and computing capacity of super computers is being brought to bear on the problem, but that there is still a long way to go. I accepted this, but I never understood the reasons for it until we took the girls to San Francisco’s Exploratorium. There, they had on display a Chaotic Pendulum that made it all clear. This thing has three interconnected pendulums that all swing about the same axis when a knob is turned.

Apparently (and intuitively), there is no reasonable way to predict the movement of the interconnected pendulums. While the movement of a single pendulum would be easy to predict with knowledge of mathematics and the input forces, it is exceedingly difficult with multiple, interconnected pendulums. Not impossible, but any very slight error in terms of the input forces or the friction on a single arm, anything…and the calculus of the motion quickly becomes flawed, at odds with reality.

And so it is with weather systems. When multiple areas of circulating high and low pressure systems collide in a three-dimensional space, it is just like the Chaotic Pendulum—nearly impossible to predict the outcome, except in the very near term, such as related on the nightly news, for those who pay attention.

–MR

I__n our twenties, we traded our boat for a house and our freedom for careers. In our thirties, we slumbered through the American dream. In our forties, we woke and traded our house for a boat and our careers for freedom. And here we are. Follow along at http://www.logofdelviento.blogspot.com/