engine repair

During summers in the 1960s, my high-school years, I worked as a helper at Shinnecock Boat Yard, on the south side of Long Island. The yard was owned and operated by Captain Conrad Egnar, his wife, Cecilia, and their clam-digging black Labrador retriever, Missy, who’d completely submerge herself, rummage around in the muck with her snout, and come back up with a clam in her mouth. The remainder of the crew included George, the summer mechanic; my best friend, Dick, who was George’s younger brother; and me. Dick and I washed decks, pumped bilges, varnished, cleaned up the shop, pumped gasoline, repaired engines, sold frozen bait to fisherman, spooled thousands of feet of line, learned about tools, and came thoroughly under the spell of living and working by the sea.

George, who attended college in the off-season, had polio as a young boy, which left him with limited control of the left side of his body. He was the first person I knew who appeared to devote significant thought simply to get his body to move. He almost seemed to have to stop and think, “I am now going to reach for that spoon” or “I want my left foot to go there.” Of course he never uttered those words, but as you watched him, you knew that was what he had to be thinking. I learned to watch without appearing to stare. When he moved across the room, he carried his left leg forward as one unit. He’d swivel his hip in a forward motion, but he had great difficulty bending his knee, even less control over his ankle, and no mental messages ever reached his toes. Likewise, his left arm could move easily at the shoulder, but he had to send deliberate messages to his elbow. His wrist, like his ankle, stayed cocked inwardly toward his body, while his fingers struggled to respond to muscle messages that were confused and incomplete. Despite these limitations, George could hit a softball farther than any of us. He could swim and water-ski, and he could repair any kind of marine engine. He was quiet, soft-spoken, and always wore a wry smile. He had a booming guffaw/snort laugh, and he was very smart. I admired him and wanted to be just like him.

Dick and I would bicycle half a mile from our homes to the yard, arriving at about 8 a.m. We got to our usual morning work. When this was completed, we were assigned to do chores for Mrs. Egnar. We might have to paint a door, weed her garden, or help move groceries from the back of her Willys Jeep. On rare occasions, she had no chores for either of us, so we’d wander around the boatyard looking for things to do. When the morning had evaporated, we biked home for lunch.

Afternoons were devoted to repair work. Dick had little interest in engines, so he assisted Captain Connie—that’s what most everyone called him—with boat repairs. Engines, however, fascinated me; I often spent the idle hours of hot summer afternoons reading engine manuals, and that’s how I became George’s assistant.

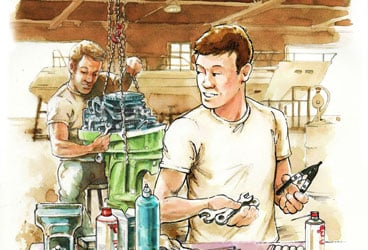

His confused body seemed custom-crafted for repairing small outboard motors. An engine would be suspended from a block and tackle attached to one of the exposed ceiling rafters. There it would hang, like a cattle carcass in a slaughterhouse, not quite touching the floor. George would sit on a small stool whose legs he’d shortened so he’d be at eye level with the engines, giving him a unique view of their intricate innards. He’d curl his left leg and arm around the engine in a way that gave his stronger, more nimble right hand incredible leverage over the engine’s often rusted parts.

On one such afternoon, George and I sat around the hanging carcass of a 25-horsepower Johnson, a large machine for its days. The upside-down engine bonnet rested on the floor next to it and made a good receptacle for the parts he systematically removed.

George had determined that one of the valves buried deep within this engine wasn’t functioning properly, thus robbing it of more than half of its promised 25 horses. This problem required major surgery, maybe even a transplant, and George was the chief surgeon. I’d be responsible for the surgical instruments but would never touch the patient. The surgery began, as did the succinct instructions.

“Screwdriver, Phillips,” George commanded. “Vise-Grips.” “Pliers.” “Socket wrench, No, not that one, the long-handled one.” “This bolt won’t budge. Get me the oil can.” I reacted to every command efficiently and silently.

And so it went for the next hour or more. Finally, we reached the vital component, the source of the engine’s ill health. We were at the most delicate part of the surgery, and George was exhausted. Beads of sweat collected on his brow, but he never lost his focus or his rhythm. Quite unexpectedly, I found myself reaching for gasket pliers, a special tool used to remove a delicate, corklike membrane designed to protect the fragile and vital parts of all engines. George had given me no command. I grabbed the pliers and thrust them in front of his right hand. He grabbed the tool, then shot me a look before turning toward the engine and carefully removing the fragile gasket.

We returned to the command/react rhythm that was typical of all of our work. “Screwdriver. No, no, slot head.” “Five-eighths-inch wrench, open ended.” “Loctite.” The operation was a success. As it turned out, no transplant was needed, only some minor cleaning; it had been an angioplasty of sorts.

At the end of the day, as always, Dick and I helped close up the shop. As we strolled toward our bicycles for the ride home, I noticed George walking toward us. “Thanks for your help today,” he said. “Maybe tomorrow you can help me with that seven-horsepower Evinrude?” In the world of the Shinnecock Boat Yard, I felt as if I’d just been given the Oscar for Best Supporting Small-Engine Repair Assistant. But I hadn’t prepared an acceptance speech. “Sure,” I said. And Dick and I rode away on our bicycles.

Francis Zappone, whose work has appeared in The New York Times_, is currently writing about his experiences cruising on the coastal waters off eastern Long Island and New England._