Once all the paperwork was done and the foundations were installed on the bottom of the ocean, it took only about a month for the first offshore wind turbines to become fully erected. And then, they were there: five of them, all in a line, standing watch over Rhode Island’s Block Island Sound like Don Quixote’s giants, spinning around and around with 240-foot-long blades to produce what will eventually become 90 percent of Block Island’s energy supply in the next few years.

And should all go well with these five wind turbines, there’s already a plan in place for the next chapter of offshore wind energy. Deepwater Wind, the company responsible for building the first five offshore wind turbines ever constructed in United States waters, has already announced that it intends to build another 200 turbines in Rhode Island waters over the next five years.

Deepwater Wind isn’t the only company in America aiming to capitalize on the rise of the offshore wind industry. The federal government recently awarded 11 leases off the coastlines of New Jersey, Massachusetts, Maryland and Virginia for the purpose of companies building more wind turbines. In California, another company, called Trident Winds, has just started working on a project to create 100 “floating offshore wind systems” (FOWs, as they’re called).

What does all this mean for sailors traveling through these waters?

All Eyes on Britain

If there’s one country that the United States is paying attention to when it comes to offshore wind power, it’s the United Kingdom. As of 2015, at last count there were 1,650 wind turbines in U.K. waters — 175 of them alone in the London Array, the largest offshore wind farm in the world. In 2008, after the United Kingdom overtook Denmark to become the world leader in offshore wind power, it was estimated that it possessed over a third of Europe’s total offshore wind resources. With all that potential, it’s no wonder the country is building up its capacity as quickly as it can.

Helping in the process is the Royal Yachting Association, which for many years has facilitated the conversation between recreational sailors and the offshore wind industry.

“Our feedback to date from our members is that they haven’t had any problems sailing through wind farms,” said RYA cruising manager Stuart Carruthers in an interview with U.K. magazine Yachting Monthly in 2012. “But it should be stressed that the wind farms we’re talking about are limited to 10 square kilometers and a maximum of 30 turbines, so the experience from that isn’t a direct read across to some of the bigger projects that are being produced.”

In 2015, the RYA published a list of recommendations about how wind-farm developers can minimize collisions by maintaining a minimum height for where turbine blades can pass. The list also called for a standardized layout of rows and columns for all wind farms.

“The RYA is representing to the developers through the government the need to maintain proper marking, to make sure exclusion zones are not put in place around wind farms, and that they meet minimum design parameters for rotor height and charted depth so that should you choose to sail through them, you still can,” said Carruthers.

X Marks the Spot

For many sailors in New England, the Block Island Wind Project hearkens back to memories of the failed Cape Wind venture from the early 2000s. Controversy erupted when developers proposed the construction of 130 turbines off Horseshoe Shoal in Nantucket Sound. Opposition came from nearly every side: fishermen, American Indian groups, and property owners concerned that wind turbines would ruin their view.

A common billboard held up by protesters read, “Right Idea, Wrong Place!” That message spoke to the opinion that wind energy was the correct move, but Horseshoe Shoal was a terrible place to erect more than 100 turbines. But where does one place a wind farm so everyone is happy?

To answer this question, Rhode Island created the Ocean Special Area Management Plan and invited numerous user groups, including recreational sailors, to come forward and identify areas of the ocean they frequented. Because of their proximity to Block Island, officials from the local Storm Trysail Club were invited to share their expertise. Members of the community identified major routes used by the cruising community as well as areas where buoy races frequently occur.

Call it smart ocean planning or simply due diligence, but many feel that the Block Island Wind Project sailed through the federal permitting process because it worked so closely with the people who use the waters so frequently. Everyone from the Lobstermen’s Association to the United States Navy was brought into the process to give as much insight as possible about the prospective sites for the wind farm.

Impact on Cruisers

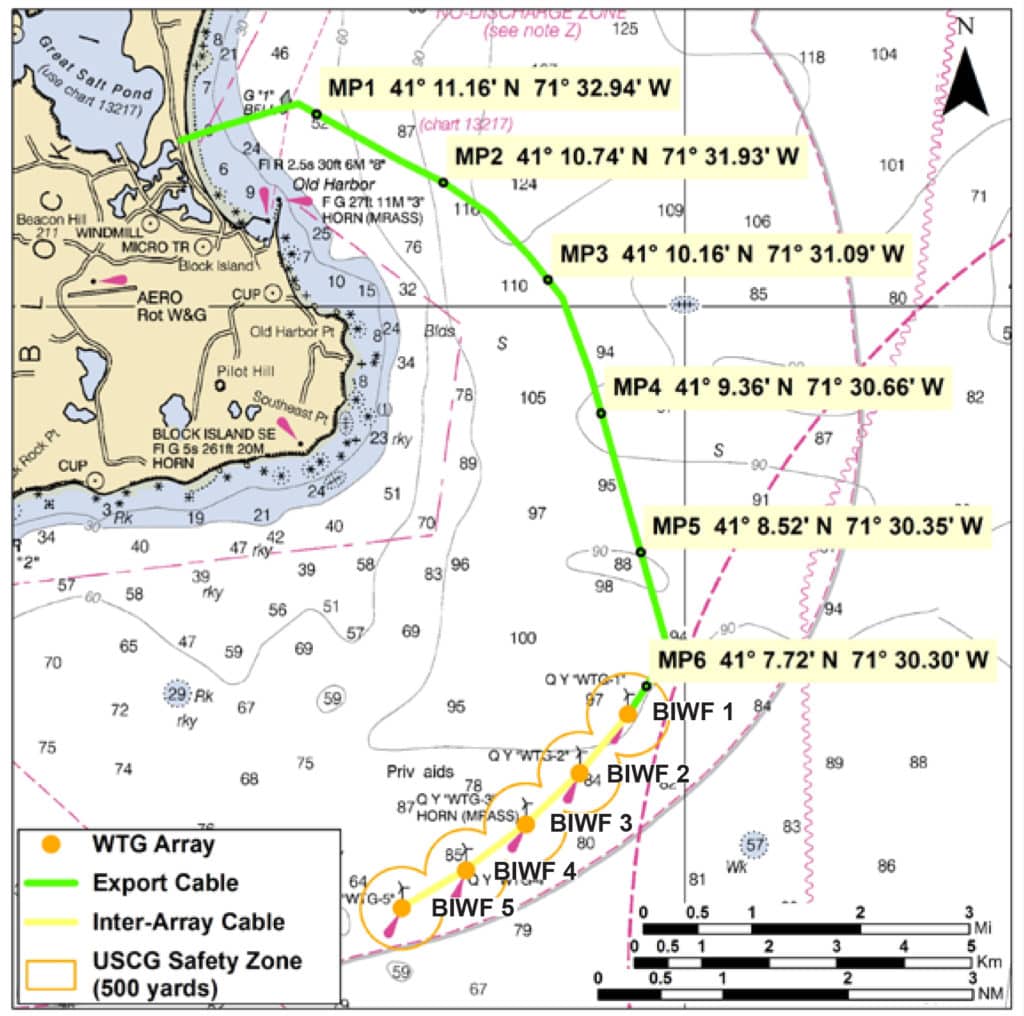

Offshore of Block Island, the United States Coast Guard established a 500-yard safety zone around each of the wind-turbine foundations while they were being constructed. Now that the turbines have been completed, however, boats are free to transit as close to the wind turbines as they wish, provided no maintenance is ongoing.

“There is no safety zone or exclusion zone when the project is in operation,” says Meaghan Wims, from Deepwater Wind. “Now that the turbines are constructed, those restrictions are no longer intact. Boats are free to roam.”

If you do plan on sailing through the Block Island Wind Farm, or any other wind farm, be aware that depending on the height of your mast, you could run the risk of a collision with turbine blades. In the case of the Block Island Wind Farm, vessels with masts higher than 85 feet should take caution while navigating very close to turbines.

From a navigation standpoint, wind turbines can be considered a nuisance, but there are also some perceived benefits. The USCG considers the turbines to be aids to navigation, and they can serve as reference points for sailors; individual wind turbines and the perimeter of the wind farm will be represented on updated NOAA navigation charts. And although the USCG prohibits sailors from mooring on or climbing up wind-turbine platforms, mariners could tie up to them in the case of an emergency.

In a survey conducted by the RYA, over 80 percent of respondents who sailed through a wind farm had no trouble navigating, and nearly a third of the respondents rated the experience as a positive one.

Sailors who have transited through Block Island Sound are well aware of how much wind blows through the region, so the introduction of wind turbines should come as no surprise. For residents of Block Island, who currently rely on expensive diesel generators for their energy, the switch to offshore wind power will come as a welcome relief.

Freelance environmental writer Tyson Bottenus is passionate about the marine environment and has worked with Sailors for the Sea and NOAA Fisheries.