To an already long list of life’s imponderables, an absolutely remarkable week floating about on Ontario’s Rideau Canal brought me to this: Is 5 mph fast or slow?

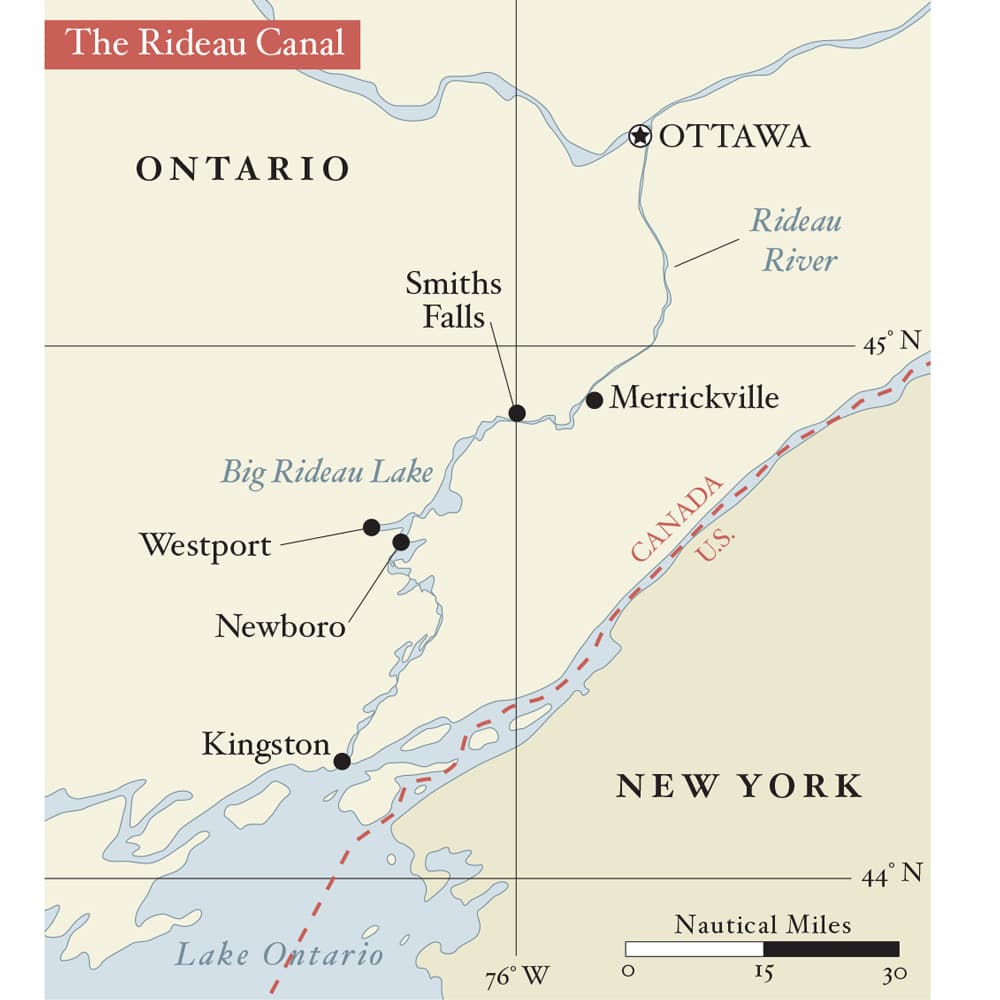

For the record, I’d not gone to North America’s oldest continually operated waterway and UNESCO World Heritage Site last July in search of an answer to that quandary. In fact, as I drove eight hours northwest from Boston to Le Boat’s newly opened base in Smiths Falls with my wife, Sue, and daughter, Rebecca, I had many more immediate things on my mind: In particular, how much of the 124-mile-long waterway could we see? From Smiths Falls, the largest town on the canal and roughly at its midpoint, should we voyage north toward Ottowa for an urban experience, or south toward the canal’s other end in Kingston for a more rural and wild adventure? And would the rest of our crew — my brother, Dave, his wife, Peggy, and photographer Jon Whittle — arrive in time to help us to provision before checking in and moving aboard a Horizon 3 canal boat the following afternoon?

Here’s the dilemma that came to perplex me, though, as we navigated 100 or so miles across vast lakes, through forests and towns, rolling farmland, and sprawling marshes: Five mph seemed quick in the narrow parts of the waterway, especially when approaching other vessels or the granite block walls at any of the 13 locks we navigated, though I grew more confident by the mile that the vessel’s powerful bow and stern thrusters would keep the boat ding-free. That same speed seemed plodding, though, as we motored into head winds and crossed long open-water portions of the Rideau. And so, with speed and distance both relative, it seemed the only certainty was that at 5 mph, we had all the time in the world to sit back, relax and savor the experience of a very different sort of floating holiday.

The Rideau Canal was built in the aftermath of the War of 1812 to guarantee the British a secure military and commercial supply route to Kingston, on Lake Ontario. British Lieutenant Colonel John By and the Royal Engineers designed and oversaw its construction, which began in 1826. Thousands of Scottish and Irish immigrants came to work on the project, and many stayed on as settlers once it opened in May of 1832. While in name a canal, the Rideau is actually a waterway comprised of predominantly lakes to the south of Smiths Falls, and to the north, the Rideau River, which flows to Ottawa. Just 12 miles of the canal were cut by hand. From Kingston, the Rideau rises 166 feet through nine locks to reach its summit at Upper Rideau Lake. From there it drops 275 feet in elevation to the Ottawa River, through a series of 19 locks. The rise and fall is important, because when navigating, red buoys are kept to the right when headed upstream to the water’s source, the aforementioned Upper Rideau Lake. As a reminder, at Newboro Lock, where the direction of flow reverses, a red-painted flowerpot is to starboard and a green pot is to port when pulling into the lock from the Upper Rideau. At the other end, the colors of the pots are switched as you enter Newboro Lake and start locking down toward Kingston.

Throughout the waterway, the vast majority of the locks are still operated by hand, using the same mechanisms the tenders have used since 1832. Massive wooden doors at either end of the chamber are opened and closed by lockkeepers turning stout black metal hand cranks. Similar mechanics control the sluices that let water flow in and out. A minimum depth of 5 feet is maintained throughout the Rideau, which is open from mid-May to mid-October.

We arrived in Smiths Falls on Friday and checked into the Best Western, just down the street from Le Boat’s base in the historic Lockmaster’s House that sits alongside the waterway. There was a full-on summer party underway behind the hotel, with pontoon boats, kayaks, canoes, runabouts and houseboats tied along the shore, and a park full of Harleys, camping trailers, tents and pickups between us and Le Boat’s new docks downtown.

At the Smiths Falls Lock, we watched a small powerboat navigate through. With a rise of 26 feet, it is the tallest single step on the waterway. Inside every lock chamber, thick plastic-coated steel cables run top to bottom every few feet. A woman at the bow and a man at the stern of the runabout led dock lines around their respective cables to hold the boat in place as lockkeepers opened the sluices and let the water flow out. The modern Smiths Falls Lock replaces three original locks nearby and is unusual because it’s one of the few on the system that operates at the push of a button.

That evening, we dined at Matty O’Shea’s Pub and sampled local delicacies such as smoked meat sandwiches and poutine — cheese curds and gravy over fries — all washed down with Canadian beer. Jon went a step further and tried the Matty’s Burger, a hamburger smothered in jalapeños and peanut butter, an incongruous combo that he deemed delicious.

In the morning, we toured the Rideau Canal Visitors Center, provisioned at the nearby Independent grocery store and paid a visit to the Beer Store, one of a handful of outlet chains permitted to sell spirits in the province of Ontario. Then, with several dock carts worth of supplies, we went off to find our boat.

Purpose-built, the Horizon 3 has a relatively narrow beam to accommodate the often-limited space in the canal’s crowded locks. In place of a toe rail and boot stripe, there are rugged rubber bumpers that run fore and aft with four additional vertical pads on each side, plus one on the stem and another across the stern, completely eliminating the need for fenders.

The boat has a small aft deck, with a sliding glass door that opens into the saloon. Inside to starboard is the galley; to port sits a table that can be converted into a bed. A helm station is to starboard amidships. We never used it during our trip, but it looked useful for cold-weather days. Forward and a step down there are double en suite cabins to either side, and an enormous berth with separate head and shower compartments in the forepeak. Comfortable and bright as the interior was, most of our driving, living and lounging took place on the flybridge, which is set up with a helm station forward, and a grill and dining table astern. Le Boat’s Horizon range also includes smaller models for more intimate crews. It took us just minutes to confirm the vessel’s design intent: Party and enjoy.

Still undecided on our itinerary, I asked a lockkeeper where he would go with a week to explore. Why not, he suggested, get a taste of the Rideau River by starting off with a visit to Merrickville, about two hours and three locks north, then return and head south to play in open lakes for a few days. Sounded good to us.

RELATED: Cruising Canada’s Gulf of St. Lawrence

So after a briefing dockside, and with Le Boat’s handyman Sterling Brown beside me at the helm on the flybridge, Jon and Dave slipped our stern lines and we were off. With a bump of the throttle, the boat crept ahead until we were clear of those sandwiched in on either side. In the open basin adjacent to the lock, we stopped. I tried backing, then gave the joystick a twist and spun a doughnut to get the feel of things. No time like the present, I thought, and pointed the boat into the waiting lock.

As we entered, lockkeepers were on hand to take our lines and I used the thrusters to push us sideways to the wall. Le Boat’s brochure was right: “No experience required.” Behind us the doors closed, Sterling bid us bon voyage and gravity lowered us to the canal below.

RELATED: The Wild West Coast of Vancouver Island

The next two locks were navigated with similar ease, even when we caught up to another crew on a Le Boat and had to tie side-by-side. We reached the third lock, Kilmarnock, well before closing time, as advised. Hours of operation are a navigational consideration not to be overlooked. Travel on the canal ends abruptly when the keepers go home for the night. As we approached, a highway bridge blocked the entrance. While we watched and waited, a lone lockkeeper leaned against it and single handedly pushed the two-lane span out of the way. Talk about a well-greased operation!

The ride to Merrickville was breathtaking. The river wound through woodlands and rolling farms, past sprawling wetlands with swaying grasses and birds. In places cornfields descended to the water; in others, small camps or houseboats sat nestled in the trees along the shore.

In Merrickville, we took a left fork just ahead of the lock in the center of town and found an open, though tight space at a dock right next to a sign warning we were about to reach the edge of a dam. Yes, my knuckles were just a little white as I grasped the thruster’s joystick to spin us and crab sideways to the pier.

The sun was low in the sky as we set dock lines. Beside us, the town common was filled with people enjoying a fine summer evening. It had been a long day and no one felt like playing chef. Instead, we took a stroll and found dinner at the Goose and Gridiron, an establishment that dates back to the 1850s and where, at the bar, the beer taps sprout from hockey goalie helmets.

Having arrived too late to really see the town, on Sunday, the crew opted to stay put. We had a couple of Le Boat’s bikes aboard, and Sue and I rode a ways out into the country. In town, we visited a few of the many galleries and shops, and then on a whim, crossed the canal and followed a dirt road down to a stretch of rapids that the lock and canal bypass on the north side of town. The road ended at Aylings Boat Yard and Marina, a living wooden boat museum, with all manner of classic cruising lake boats in various stages of repair. Inside a shed, a do-it-yourselfer gave us a tour of his replanking project, a labor of love that was clearly being measured in years. Beside him, a just-refinished 40-something-foot cabin cruiser sat waiting to be launched. It was such a good show, I returned to the boat and got the rest of the crew. We paid a second visit to Aylings, and then followed a path along the river to another yard, Sirens Boatworks, which specializes in restoring old Chris-Crafts and new boat builds. Its owner talked excitedly about the ongoing wood revival on the canal.

Monday we were off the dock early and waiting at the first lock when it opened for business. South of Smiths Falls, the canal at first was much the same: a narrow winding waterway surrounded by forests and marshes. Once through Poonamalie Lock, though, we turned a corner and Lower Rideau Lake lay before us. The breeze was blustery, with gusts into the 20s; combined with the chop, it cut our speed by a half a knot or better. No matter, the view was grand and the channel across the lake was well marked and easy to follow. We passed the small town of Rideau Ferry, a relatively narrow spot that marks the boundary between Lower Rideau and Big Rideau lakes. The ferry had long since been replaced by a highway bridge, but the name lives on.

Big Rideau is about 20 miles long and three wide, and sprinkled with islands. Cottages dot the shore amid bold granite outcroppings. Our destination was Colonel By Island, where Parks Canada maintains docks and moorings, all nestled in behind several tiny islets, each of which somehow held equally small summer camps. There was one other boat tied up when we arrived and a few kayakers had set up tents on the lawn above. In the evening, with a new moon and clear sky, the Milky Way was spectacular. So much so, Jon headed for solid ground to set up a camera to shoot the night sky.

The wind died completely by morning and the lake was like glass. We attempted a hike inland but were quickly driven back to the boat by voracious mosquitos. After breakfast and a swim, we pushed upwards through the Narrows Lock and into Upper Rideau Lake, the high point of the waterway.

At Newboro Lock, the keepers gave us a friendly reminder about the change in aids to navigation. Separated by a short, narrow stretch of canal, Newboro Lake couldn’t have been more different than the broad and open Rideaus. Here long granite islands run in rows, as though some ancient hand had used fingernails to scrape out the slices of water between them. Across Newboro, the channel became twisted and took us through two much smaller lakes, Clear and Indian, before we arrived at Chaffey’s Lock, our destination for the night. Most of the locks we visited had just a lockkeeper’s house on site, but at Chaffey’s, the shores were lined with small cottages and we spotted a marine repair shop and store. The docks at the lock were busy with several boats already tied up for the day. Here, as at many of our stopovers, curious onlookers asked about our Le Boat and gladly came aboard for a tour of the curious looking craft.

Nearby, we found The Opinicon, a recently restored and reopened circa 1870s hotel, a point of pride with the locals and a good place for a cold beer on a warm day. As dark fell and the mosquitos came out to feast, we fled the boat and returned to the resort to test out the skills of its bartenders.

There’s a point in every charter vacation when you realize you’re running out of time. Our “uh-oh” moment came Wednesday morning. Before starting back north to visit Westport, a recommended tourist spot on Upper Rideau Lake, we very much wanted to see Jones Falls, where a man-made dam and four waterway steps have been described as one of the “Wonders of the Rideau.” Though we got an early start and passed through two sets of locks quickly, when we arrived at the falls several boats were already circling. We would have to wait at for least two or three lock-throughs, each of which might take a half hour or longer. Adding up the delay plus the hour or so we’d need to look around, we weren’t certain we could make it back though all the locks and still make Westport by evening. Time, then, to retreat.

Westport lies off to the west of the main channel that crosses Upper Rideau Lake and, surrounded by farms, is easy to spot from afar. We arrived midafternoon at the town marina, located on a tiny island connected to shore by a footbridge. A couple of cheerful dockhands showed us to a spot for the night, pointed out the favored ice cream parlor (every Canadian village has one) and suggested that if we wanted to take a walk, we should visit the local winery.

As in any lakeside tourist town on a July afternoon, the downtown was bustling with small shops, restaurants and traffic, but we quickly escaped all that as we followed the highway out into the country. After several days on the boat, we welcomed the couple-mile walk to Scheuermann Vineyard and Winery, which we found up a dirt road that took us past acres of grapes that Allison Scheuermann and her chef husband, Francois, had planted nearly a decade earlier.

After a brief tour, the six of us sat at a long open-air table while Allison introduced assorted bottles of whites and reds. Nearby sat a large stone oven where pizzas are grilled and a recently built awning that shades tables set up for family style dining. The wine was delicious and the views out across the hills were magnificent on this blue-sky afternoon.

At the boat we took a swim to cool off, then sat on the flybridge to watch the sunset and enjoy Peggy’s Thai basil fish dinner. Afterward, we wandered back into town and caught the last set of music at The Cove Country Inn, a nearby restaurant and watering hole.

Since we had to have the boat back at the dock in Smiths Falls early on Saturday, before the locks opened, our options for Thursday were limited. We wanted to be within an easy day’s run on Friday, so after paying $10 to fill our water tanks, the crew voted to head back to Colonel By Island, where the night sky had been so dazzling.

All week, boat traffic on the Rideau had gotten busier. This time approaching the lock at the Narrows, rather than sweeping right through, we found a waiting queue. At By, the docks were full, so we picked up a mooring ball instead. It was a hot afternoon, and the lake water was refreshing. Rebecca perfected her cannonballs from the flybridge, and we tried out the pool noodles she’d bought at a dollar store in Westport. Damselflies and loons entertained us as we cooked a last dinner aboard and watched the sun set. What a life!

Friday, the breeze was at our backs as we cruised north past Rideau Ferry again. With a bit of time to kill, we checked out Beveridges locks at the entrance to the Tay Canal, which leads to Perth, a reportedly lovely town that would have to await another visit. We motored to the center of the lake, killed the engine and drifted while we cooked lunch. Then with afternoon shadows lengthening, we headed back to the base, hit the gas dock and tied up for our last night across the basin from the Le Boat docks, alongside a park in the center of town.

A week on the Rideau had worked its magic. We were rested. We were happy. We’d tried something entirely new on a waterway built nearly 200 years ago. In the end, our 5 mph pace had proven to be pretty near perfect.

Mark Pillsbury is CW’s editor.